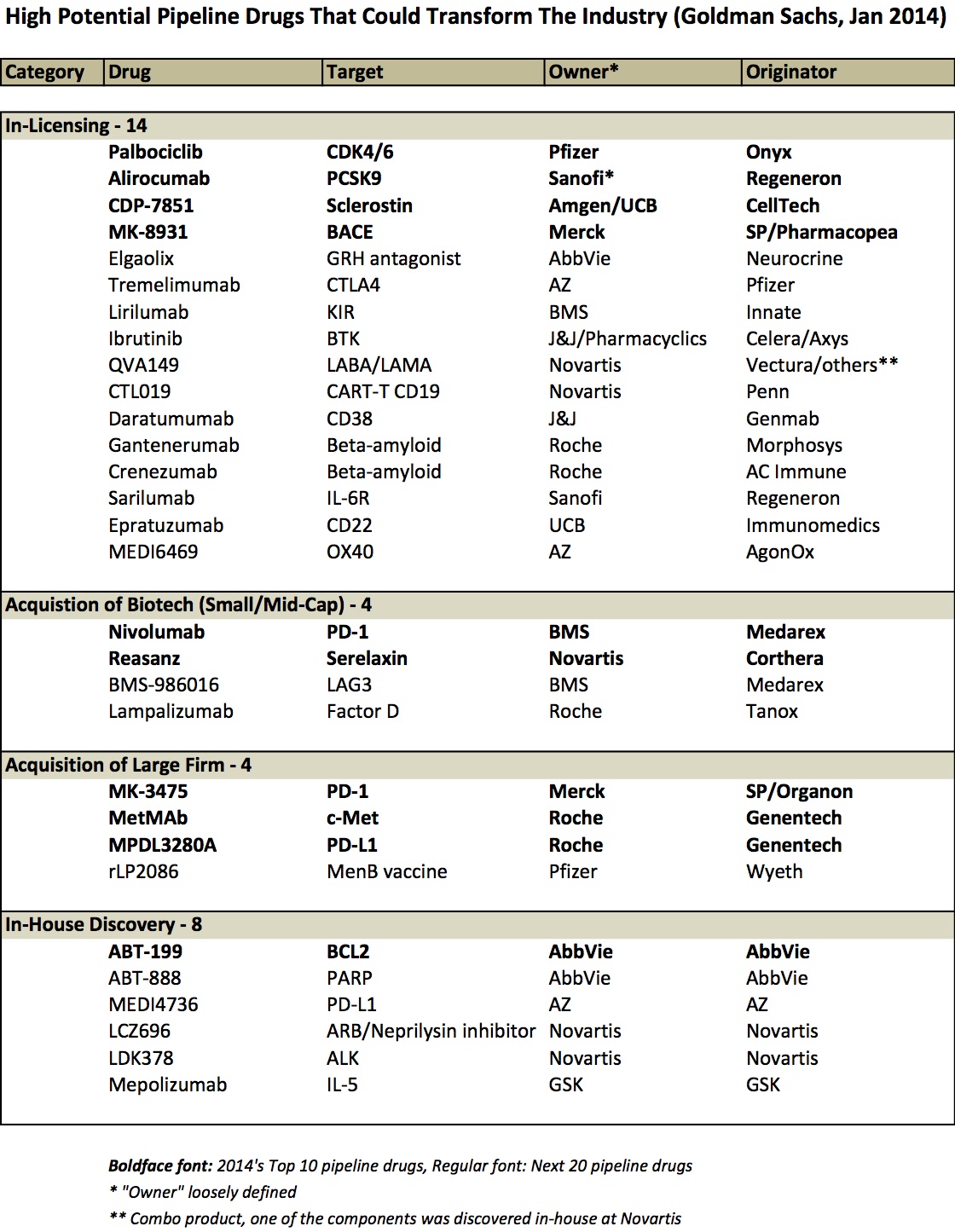

Today’s biopharma industry has a richer and more exciting late stage pipeline of compelling new therapeutics than its had in years, drawing lots of enthusiasm from analysts and investors. Goldman Sachs (GS) recently published a report on the “10 drugs that could transform the industry” (Jan 2014), highlighting how many of these drugs have “game-changing commercial potential”, and that these drugs will help the industry “move beyond the cliff” of patent expiries. The GS healthcare team has put this “10 drug” snapshot out for the past few years and it’s always great list of inspiring therapeutics.

This year’s “top 10” won’t surprise many readers: it includes three immuno-oncology programs against PD-1/PD-L1, and an additional three against other cancer targets (BCL2, CDK4/6, and c-Met). The GS team also highlights another twenty drug programs that are “in mid/late stage clinical development that are either earlier in development or we have seen less clinical data” but are potentially high impact as well. Although I’m sure there are many programs of great interest that are missing from the list, these 30 programs represent a good proportion of the “cream of the crop”.

While the list itself is interesting, and each drug could be a blockbuster, I wanted to call attention to something the Goldman report and many others haven’t highlighted directly: the instrumental and essential role of smart business development deal-making underpinning these projects.

By my quick review, it appears as though ~75% of these drugs originated at firms different from the company that owns them today (or owns most of the asset today) – either via in-licensing deal or via corporate acquisitions. Savvy business and corporate development strategies drove the bulk of the list. Here’s a table that captures it:

Few observations:

- Licensing deals predominate as the primary source of these innovative late stage pipeline programs (15 of them). Some came out of broad multi-program partnerships (Alirocumab and Sarilumab are both from the Sanofi-Regeneron relationship), but most from single product focused deals. And most of them evolved from partnering deals done more than five years ago.

- Several 2009 acquisitions are present in this list. BMS completed its “string of pearls” deal series with the capstone $2.9B acquisition of Medarex in 2009; this deal brought two drugs on the list above, including nivolumab (which Medarex itself got via its deal with Ono) and BMS-986016 (Anti-LAG-3). Roche’s acquisition of Genentech was finalized in 2009 (bringing MetMab and MPDL3280A from this list), as was Pfizer’s acquisition of Wyeth (rLP2086).

- Acquisitions of smaller biotechs are rare on this list – only Tanox and Corthera, on top of Medarex. That’s an interesting observation. I suspect this reflects that licensing deal numbers vastly outpace acquisitions and that volume bias is reflected in the differential here. But another hypothesis is that biotech acquisitions just haven’t delivered (vs licensing); I’m skeptical of that being true, but I’ve never seen data on it. (Any reader with that data, please share).

A bunch of other great pipeline drugs aren’t on the Goldman list. Many of these exciting programs were discovered in-house, like secukizumab/IL17A (Novartis), lebrikizumab/IL13 (Roche), and others.

But I suspect that in a review of the entire late stage industry pipeline, the imbalanced ratio of external:internal sourcing would largely be intact. For instance, most of AZ’s late stage pipeline is externally-sourced: Lesinurad/URAT1 (AZ acquired via Ardea), Naloxegol/opioid (AZ licensed from Nektar), Brodalumab/IL17 (AZ licensed 50/50 from Amgen), Epanova/omega-3 (AZ acquired via Omthera), Selumetinib/MEK (AZ licensed from Array), and Benralizumab/IL-5 (AZ licensed from BioWa). Furthermore, many other notable late stage drugs were brought in through partnering, like elotuzumab/CS1 (AbbVie/BMS, discovered at PDL), empaglifozin/SGLT2 (BI partially licensed to Lilly), baricitinib/JAK (Lilly licensed from Incyte), Mekinist/MEK (GSK licensed from Japan Tobacco), and LEE011/ckd6 (Novartis licensed from Astex).

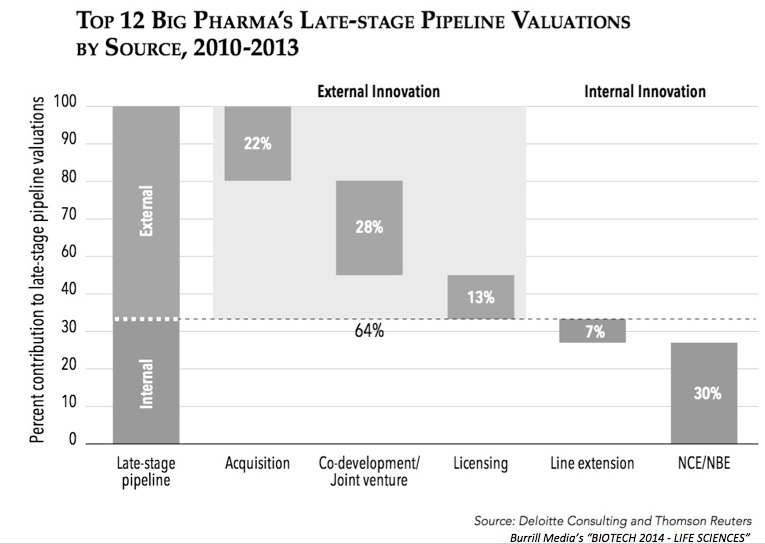

My quick review above is in line with a recent analysis from Deloitte showing that 2/3rds of the valuation of the industry’s late stage pipeline is from externally-derived programs; a graph from the recent Burrill report sums up that data:

“Partner of Choice”

Based on the preponderance of externally-sourced programs in the “cream of the crop” of the industry’s late stage pipeline, it’s no wonder than that every big drug company wants to be “Partner of Choice” with smaller innovators. Nearly every pharma has hired consultants at some point to help it position its BD strategy more effectively. They all host “VC Days” to engage the startup biotech investing community. Most have brochures describing what they are looking for, and how great they are with testimonials from current and prior partners. JP Morgan, BIO, BioEurope, and the rest of the partnering meeting circuit are always full of Pharma scouts looking for deals. All these things are good, and the attention to partnering is of important value, especially in light of the analysis above.

But the reality is the key ingredients to being a real Partner of Choice aren’t rocket science, and can be summed up with “Five C’s”:

- Capabilities: do you have the requisite R&D skills to develop the program?

- Clarity: can you get to a clear answer on the deal quickly vs bureaucratic feet-dragging?

- Commitment: where does this fit in your future R&D strategy/priorities, and are you playing for the upside or protecting the downside with this deal?

- Capital: are you competitive on the economics terms, including upfronts, milestones, co-whatever rights, and (importantly) commitments of future program funding?

- Chemistry: have you created the right personal relationships and trust?

The best BD teams in the industry win deals for their R&D colleagues by delivering on those Five C’s, amongst other things.

Two final comments about the financial and risk-management elements of deal-making.

First, it clearly costs money to do deals. Many argue about the expensive nature of deal-making vs in-house work, but the reality is if an asset is cheap, you probably don’t want it. Pharmasett’s acquisition by Gilead looked outrageous at the time, but looks pretty smart now. Same goes for Medarex’ acquisition by BMS, J&J’s deals with Pharmacyclics and Genmab, Novartis’ Corthera deal – all involved big numbers. Even early stage deals can raise eyebrows: Celgene’s $120M into Agios’ discovery stage story was a surprise then, but looks pretty smart now (its equity ownership alone nearly paying for the deal, not to mention the product rights). The key is to being comfortable with higher economics is to build relationships early, know the science better than others, and follow the evolution of programs over time (tracking their data flows); this way, there’s a level of trust in the integrity of the scientific work that enables a more positively-inclined, “lets make this work for everyone” deal-making posture (and less of the paranoid “you must be out to cheat me” phenotype). Creative deal structures help too. Getting to a good “yes” on a deal is hard, often expensive, and takes relationship-building.

Second, given the attrition rates in our business, it’s likely that most products brought in through deals will fail. This should be expected. While in-licensed drugs used to have a higher success rate in development (see Fig 6b here), I’m not sure what the latest statistics are so lets assume similar failure rates. Many deals clearly succeed – the 75% of the list above are Exhibit A in favor of doing deals. Many of these were true risk-sharing deals, with structures aimed at helping mitigate some of the potential attrition risks through biobuck payments and the like. Importantly though, its worth noting that “risk-sharing” is not the same as “risk-shifting” – deals where the biotech absorbs all the risk and isn’t rewarded for their innovation-to-date upfront in the deal, or ones where Pharma takes on all the risk. Appropriate (and significant) returns for innovation should accrue along the value chain. Given the attrition rates we face, the other alternative to doing smart deals is to simply find a reason not to do the deal – there are always many reasons. Making it even more daunting, it’s clear that getting to a “no” is both easy, less expensive, and right a majority of the time. Therein lies the dilemma of deal-making.

In recent years, partnering has driven a ton of value in the drug business – and will increasingly do so as the pharmaceutical ecosystem continues to (at least partially) de-integrate the traditional “not-invested-here”-biased FIPCO into a plethora of early stage innovators feeding new product candidates to bigger development and commercialization firms.

[Note – edits to table made in late March 2014 with input from comments]