This blog was written by Jason Gardner, CEO and co-founder of Magenta Therapeutics, as part of the From The Trenches feature of LifeSciVC.

There’s a proverb that goes like this, “If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together; but if you want momentum, go with tailwinds.”

The first two parts of this proverb apply to many young biotechs that move quickly by being focused and the need for an array of partnerships and long-term investors to go much farther.

Gaining momentum, however, is the elusive amplifier of a company’s mission. From our early learnings in building Magenta as a therapeutics company with the aim of transforming stem cell transplant medicine, catching tailwinds to harness momentum is critical.

Momentum. The essential ingredient for any company that blends data, people, and the plan with multiple elements synergizing at the right time. As with the sports team that gets into a winning groove, momentum can have a big impact on business progress from within a company as well as from the outside world.

Measuring, or even detecting biotech momentum, other than in hindsight, is often hard. All investors look for it, and scientists often know it first through a great set of data in the lab, growing support from key partners, or a manuscript acceptance from a top journal. There isn’t a single definition of what momentum looks like, but it unmistakably comes together to drive a company farther and faster. There have been real tailwinds in the cell and gene therapy space in recent years, and we at Magenta are seeing major indicators of momentum in the transplant field based on strong science and clinical studies that are quite distinct from hype.

As an example, the patient responses with CAR-T trials in 2010 represented early indicators of momentum in T cell-based immunotherapy, leading to a seminal publication for the field in NEJM in 2011. Company creation and partnering activity accelerated in the immediate years following, as described here. The recent landmark FDA approval of the first CAR-T therapy, called Kymriah, and the massive acquisition of Kite Therapeutics in August, represent another round of momentum drivers. Similarly, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology has captured the attention and excitement of the world over the past five years, and it will be fascinating to watch this technology move to the clinic where even bigger bets will be placed. I blogged on the hype-hope cycle of both of these technologies here last year.

We work on several therapeutic modalities at Magenta, where we are developing a portfolio of medicines with the potential to transform hematopoietic stem cell transplants into a much more effective, safer and broadly used treatment modality to change many patients’ lives. We have generated new data on targeted antibody toxins, novel mobilizing agents, and stem cell expansion programs, each of which aim to address key challenges in the transplant field. This early progress has enabled us to finance, recruit, and generate data while establishing partnerships with companies and clinical collaborators to develop our programs. Internally, we are working hard to build and advance our technology, but we are also catching some tailwinds to ride the momentum in transplant medicine.

Transplant Tailwinds

Momentum in transplant medicine is unique because this is not a new field of medicine like CAR-T and CRISPR-Cas9. Rather, we are looking to drive a renaissance through the application of innovative science from other disciplines. The treatment is intended as a one-time cure, and more than 1 million patients have had a transplant in the past 50 years. The science underpinning today’s clinical medicine is founded on well-studied stem cell biology. However, transplant can be a cumbersome and dangerous procedure, compounded further by the fact that it is often hard to find a matched stem cell donor. Consequently, it has been relegated to the last-ditch option for many patients with advanced diseases like cancer. But transplant can cure and has a big impact on both patient’s lives and the healthcare system.

At Magenta’s first Board offsite retreat this summer, we reviewed our progress, plans and strategy, including our newest members since our Series B round and transition to a clinical stage company. We also talked about the “transplant tailwinds” that have been quickening this year. These are a set of parallel clinical developments that have been published, several from our collaborators, and which affirm and extend our primary thesis that stem cell transplants provide curative therapies for many patients, including those with autoimmune, genetic diseases or blood cancers.

There are echoes of the earlier events in the CAR-T field but taken together, the three tailwinds confirm our foundational hypotheses underpinning Magenta’s vision:

1. Stem cell transplants have curative benefit in autoimmune diseases, but the safety profile remains a real barrier.

A pair of comprehensive reviews published this summer in Nature journals have summarized the clinical transplant results in multiple sclerosis (here), and broader rheumatic autoimmune diseases (here). The main conclusions from this combined experience in over 3000 patients during the past 20 years are:

-

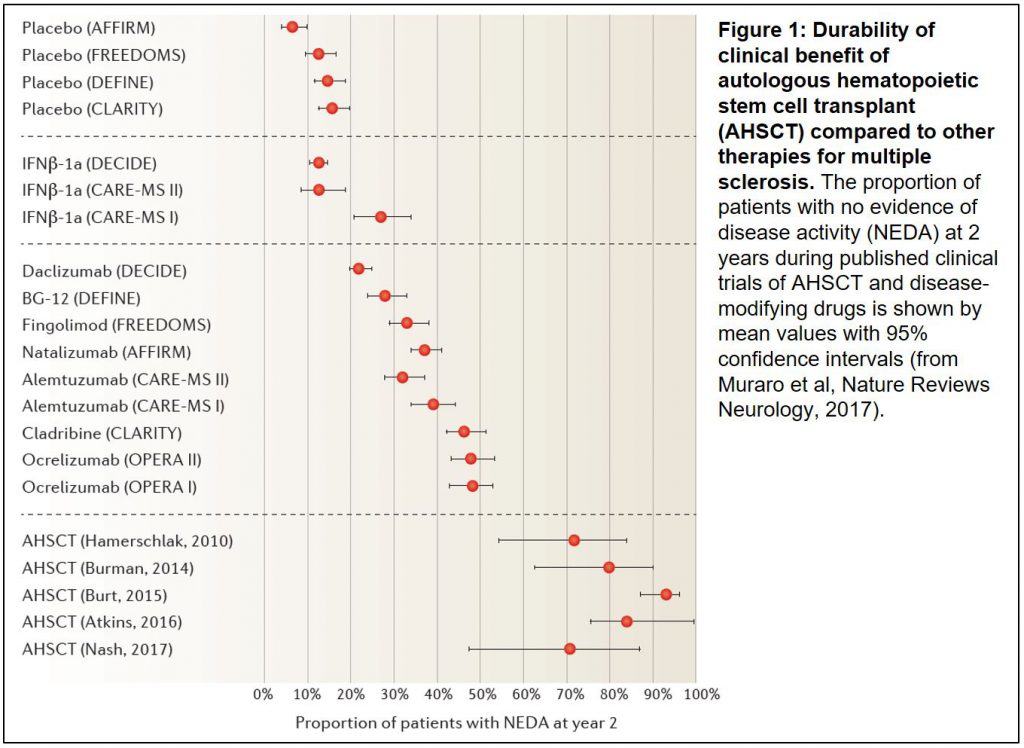

- The therapeutic benefit of stem cell transplant is significant across multiple studies in severe autoimmune diseases: Relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS; 5 Phase II trials) and systemic sclerosis (2 phase II trials and 1 Phase III trial) have the most clinical evidence using stringent disease endpoints. When compared to the standard of care in RRMS, the proportion of patients with clinical benefit at 2 years appears to be double that of the next best treatment (Figure 1).

- The side effects of the patient preparation for transplant (called conditioning) are serious. Although transplant-related mortality has been reduced to less than 5% over recent years, the complications of the toxic chemotherapy and radiation that are currently used need to be carefully weighed against the disease benefit. Transplant remains an option for only the patient groups with most severe disease, many of whom have progressed on other lines of therapy – this highlights just how difficult these patients’ diseases are to treat, making the making the dramatic and durable clinical responses seen with transplant even more impressive.

- A reset of the immune system is thought to be a potential mechanism for the clinical benefit of transplant in autoimmune disease. Mechanisms for the immune reset require further investigation but appear to require renewal of a diverse Treg compartment. There are a lot of translational medicine studies ongoing to illuminate our understanding of this biology.

In both papers, the authors conclude that more patients with these autoimmune diseases could be transplanted today. Indeed, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), a European non-governmental organization which represents the people with arthritis/rheumatism, has approved new guidance proposing greater use of transplant for systemic sclerosis, and Sweden recently approved it for RRMS. We know that momentum, particularly in Europe, is clearly building in support of transplant as these recommendations are being implemented. Results of new trials in systemic sclerosis are expected before the end of this year, and a large global Phase III trial of transplant will be started soon to compare the procedure to approved therapies in RRMS. The retrospective meta-data look compelling for transplant, and it will be interesting to see this evolve over the next few years.

At Magenta, we know that patients are waiting for improved transplant drugs that don’t carry the life-threatening toxicities of the current conditioning regimens. We gathered a group of experienced physicians from these fields at our Scientific Advisory Board last week to discuss how we can best bring new therapeutics forward as effectively, safely and quickly as possible. The room was full of enthusiasm for our targeted conditioning approaches to reduce the side effect problems and open up this potentially curative therapy to many more patients. The advice we heard from leaders in the transplant and autoimmune fields was that these innovative therapeutics are needed, and the early partnerships that we are establishing with autoimmune groups will be vital as we move forward together. It will be a fascinating journey. More to follow

2. Transplants with stem cells from umbilical cord blood are very effective at treating children with genetic diseases beyond cancer, but only when the donor is well-matched to the patient.

One of the biggest difficulties for families with a child battling a genetic disease of the blood (e.g., sickle cell disease), immune system (e.g., SCID; ”bubble-boy” disease) or metabolism (e.g., leukodystrophies) is that while stem cell transplant can be curative, it is very challenging to find a donor with a closely-matched immune system (HLA-typed). When transplants are done with partially-matched donors, the risk of death from failure of the stem cells to engraft is significant, and these odds can be overwhelming for many patients when they have to make the transplant decision.

We know that umbilical cord blood contains stem cells which are effective in transplants, and that millions of these cord blood units are stored away, frozen in public and private banks. However, finding a well-matched cord blood donor for a patient is complicated, as most umbilical cords contain an insufficient number of stem cells to achieve a successful outcome, especially when the patient enters their toddler years and more cells are needed for the transplant.

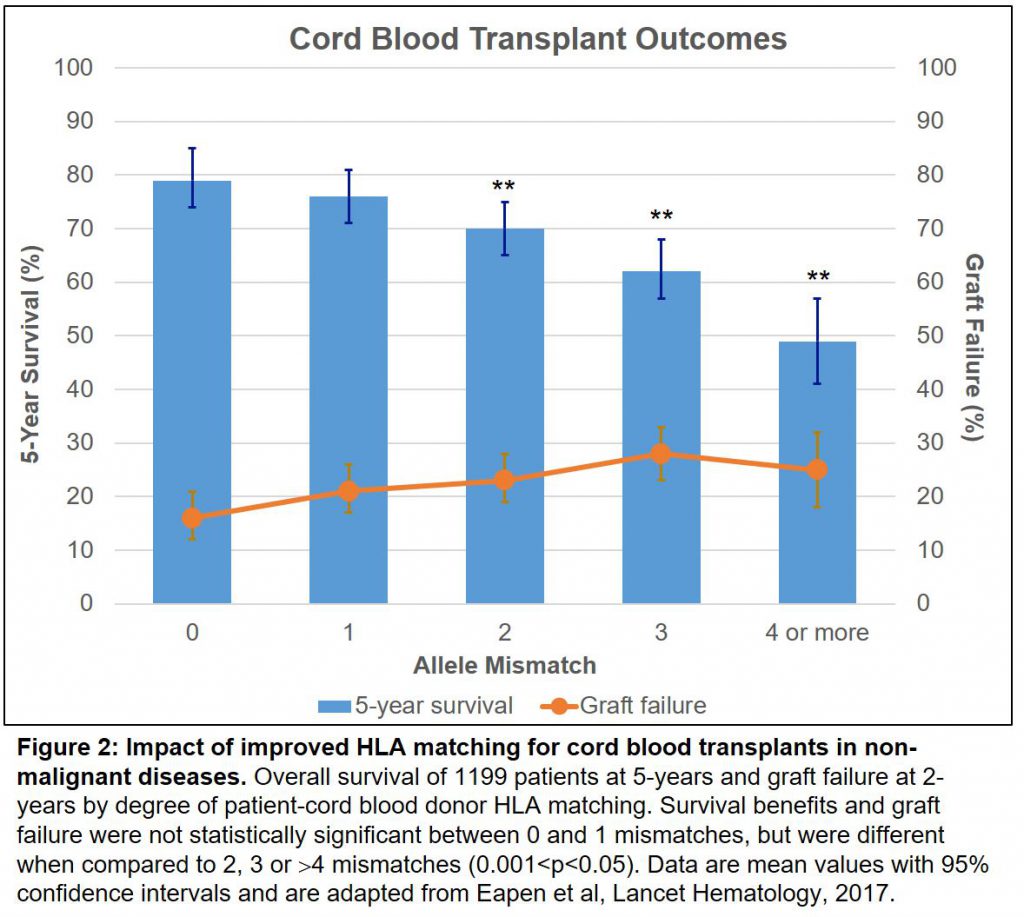

In a new comprehensive retrospective analysis published in the Lancet, our partner physicians at Be The Match, the lead non-profit organization facilitating transplants globally, studied the outcomes of nearly 1200 children who were transplanted over a 10-year period with cord blood (here). The collaborative group, led by Drs. Mary Eapen and Mary Horowitz, found that the majority (up to 80%) of patients had durable survival benefits when their donor was closely “haplo-matched” (at 7 or 8 of 8 HLA allele level). This success quickly diminished to 41% when cord bloods with lower degrees of match were used, and transplant failure increased (Figure 2).

What does this mean for patients? A one-time therapy that results in profound long-term survival is a life-changing medicine, and many of the successfully-transplanted patients will require no further treatments (e.g., no enzyme replacement therapy). The opportunity to increase the probability for a patient to find a matched donor is an area of intense focus for Magenta, and it was a main driver for us to bring in a stem cell expansion program in partnership with Novartis earlier this year, called MGTA-456. By expanding cells from banked cord blood, MGTA-456 allows the majority of patients to find haplo-matched donor cells.

This was science that key Magenta scientists had discovered and developed over the past 10 years while working at Novartis, and they recently showed that MGTA-456 increased the numbers of stem cells by 300-400 fold in culture, resulting in 100% engraftment rates in transplanted patients with well-matched cord blood donors. We have been setting up new clinical studies in similar diseases reported in the Lancet study, where patients are waiting for a transplant but cannot find a donor. We believe that this technology will provide new hope for these families and are excited to launch the first clinical trial later this year. We’ll be talking more about these programs and plans at the ASH annual meeting in December.

3. Clonal hematopoiesis, or the accumulation of mutations in blood cells due to age, is a much bigger clinical problem we thought and it starts during middle age.

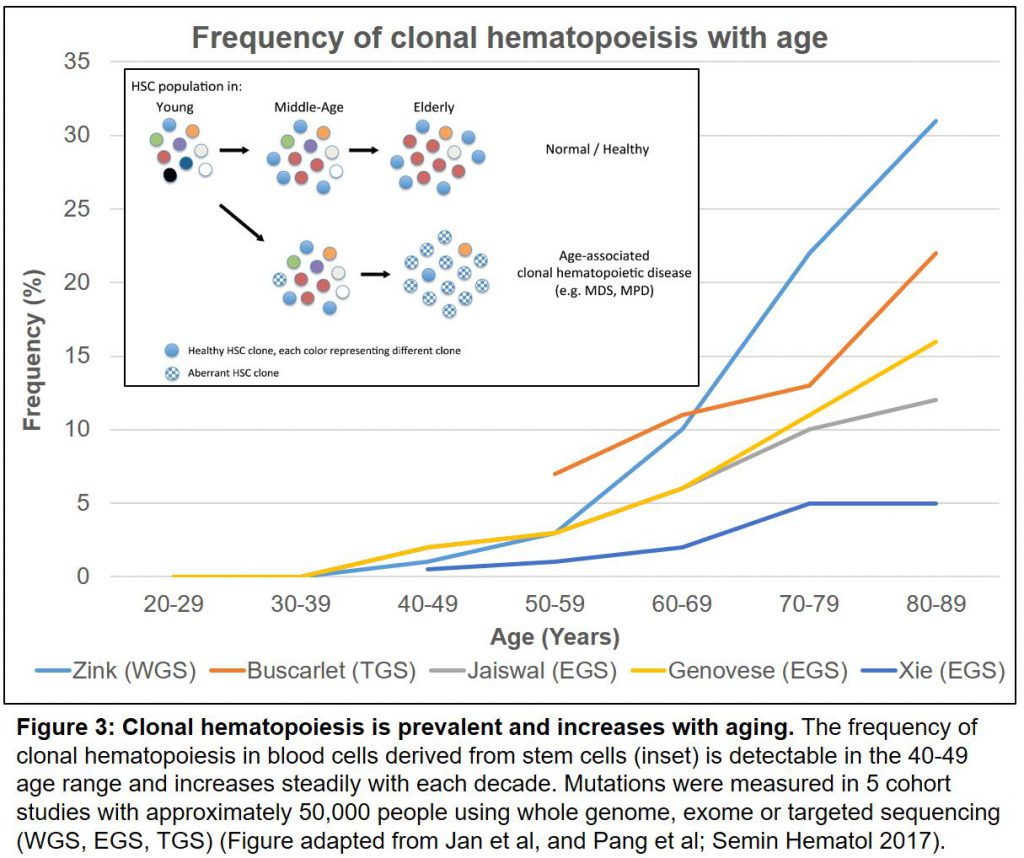

Aging is tough. We need our stem cells to produce large numbers of diverse immune and blood cells to protect us from diseases ranging from infections to cancer. As we grow older, however, we are accumulating mutations by clonal hematopoiesis in our stem cells much more frequently than previously believed. This carries an elevated risk of developing several diseases and a shortened life expectancy.

A pair of large cohort studies in the New England Journal in 2014, showed that these well-known and ominous mutations, in turn, increase our risk of developing not only blood cancers (X50 fold) but dying of all causes (by 40%), in particular cardiovascular diseases like atherosclerosis and stroke (reviewed here). These striking conclusions launched a set of follow-on studies that were published this summer. First, the increased risk of death due to cardiovascular disease associated with these mutations was confirmed in further clinical and animal models (here). A pair of new cohort analyses (reviewed here) now show collectively, from >46,000 people in 5 studies, that by the age of 60, more than 10% of us will carry at least one of these mutations (Figure 3).

We will see more mechanistic studies coming out on the role of mutated blood cells in cardiovascular and other diseases. The analogy as we age with clonal hematopoiesis is akin to playing chess where the endgame is decided with the pieces you have left on the board (credit: Magenta Scientific Founder, Dr. David Scadden). Dominant clones from mutated stem cells in the blood system do not leave many options to fight these diseases, and may even drive malignancies and cardiovascular problems just as a few autoreactive clones cause autoimmune diseases.

Rebooting back to a full-immune repertoire and blood system through a safe stem cell transplant could be very beneficial to resetting clonal hematopoiesis. Imagine in a few years’ time as part of your annual physical that alongside your cholesterol and hemoglobin levels you scroll down on your smartphone app to find the set of mutations from your sequencing results. You have a greater than 10% chance at your 60th birthday that you will be carrying a mutation that confers an increased risk of developing a blood cancer or dying of a stroke. You pause to wonder: What should I do? Diet and exercise, a statin or two, and other drugs may help but they are not going to change that mutation. Your doctor suggests rebooting your blood and immune system to get rid of that mutation through a stem cell transplant.

You could then benefit from this procedure as an intervention in medicine, rather than a therapeutic setting after the disease has started. If we can make the procedure safer, then you could either have your stem cells corrected through gene editing, or use some of your own mutation-free stem cells that you banked when you were younger, or you have an identical-matched relative who donates their stem cells for you. Younger donors, under 40 years old, are the preferred choice for transplant patients today, as they have fewer mutations and appear to engraft more effectively. Your grandchildren’s cells may be an ideal option. This is still a nascent field, but we might expect more results coming from larger studies as physicians and regulators contemplate the use of this type of blood screening as an early warning test for later clinical problems.

The Momentum of Motivation

It’s energizing to feel the momentum from these tailwinds supporting our hypotheses at Magenta, and even more satisfying that we are partnering and starting collaborations with pioneering groups in this area of medicine. However, for our team at Magenta, we have a long way to go.

Our strongest tailwind is the motivation and urgency of knowing that patients desperately need transformative therapies, and the inspiration from brave patients like Jennifer Molson (here), whose life was devastated by multiple sclerosis and enrolled in one of the transplant trials in Canada:

“Before my transplant I was unable to walk or work and was living in assisted care. Now I am able to walk independently, live in my own home and work full time. I was also able to get married, walk down the aisle with my Dad and dance with my husband… I have been given a second chance at life.”

Jennifer’s transplant was more than 15 years ago. Today, her disease is in “durable remission” and she does not take any MS medicines. That’s a powerful tailwind!