The sustainability of the biopharma sector depends on a continual flow of new startups to both feed Big Pharma’s pipelines and to create the next generation of emerging mid-cap companies. At the BioPharma America conference this week, several panelists asserted that we aren’t starting enough new companies to resupply the “corporate pipeline” for future acquisitions, and that this was leading to fewer maturing mid-cap biotech biotech companies and a dearth of compelling biotech assets.

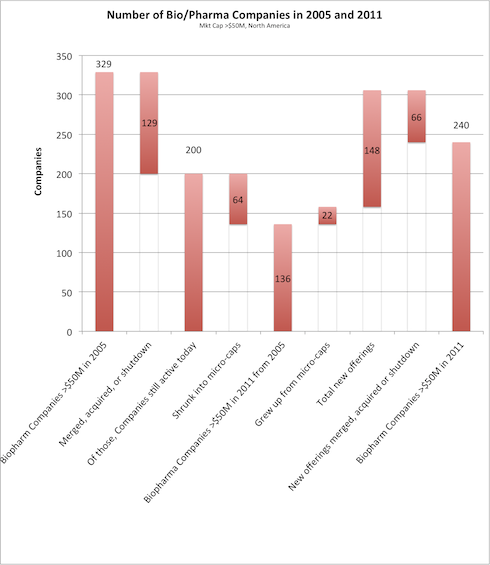

Based on a quick analysis of Capital IQ data, there certainly has been a significant reduction in the number of small, mid, and large-cap companies in our sector. In 2005, there were 329 pharmaceutical & biotech (“biopharma”) companies with market cap’s from $50M up to $200B in North America. Today there are only 240 companies bigger than $50M, or a 27% reduction in just over five years.

I’ve tracked the flow of companies in the chart below: 129 of the original 2005 cohort were either merged, acquired, or shutdown, representing almost 40% turnover. A good deal more shrunk into micro-cap land, leaving only 136 as active operating companies today above $50M. However, there were obviously some additions: a few grew out of being micro-caps, but most came from the 148 new offerings. During the time period, roughly 40% of those disappeared to M&A, shutdown, or banishment to micro-cap land. Interesting to note it was the same percentage loss to M&A or shutdowns as the original 2005 cohort. This leaves us with the 240 companies today. I caveat that this is a quick analysis with Capital IQ but its certainly directionally correct.

So while the data might not be as bad as some suspected, it still raises alarm bells as it can’t go on much longer like this without hollowing out the small- and mid-cap universe of biopharma companies that make up a critical and dynamic part of our ecosystem.

There a few drivers of the shrinking trend: not enough companies are maturing into public companies, not enough new ones are getting started, and/or too many are disappearing into mergers.

I think the first of these has far more to do with the disappearing statistics and the sentiment voiced at the conference: there’s really not an open, viable path for biopharma “maturation” today. In order to have a sustainable, stable-or-growing pool of emerging biotechs we need to have a functioning IPO market for biopharma today that can provide low cost-of-capital growth funding for aspiring companies. Public market pricing is often more punitive today than just staying private (unlike the first 25 years or so of biotech). There are at least 75 biopharma companies who have raised $75M or more in equity capital from private sources, primarily venture capital. This represents a large backlog of companies that would certainly consider going public if there was an appetite for public funding of early stage companies aiming to become the next Gilead, Vertex, or Celgene. Sadly, the only companies that seem to get public are those that reformulated an active drug or in-licensed someone else’s later stage compounds (e.g., TZYN, SGNT, ZGNX, PCRX, ACRX, HRZN, AVEO, etc…). If we really want to build a solid pipeline of maturing research-driven public biotech companies then we need to figure out how to get public investors more excited about novel biopharma. Exactly how to do that isn’t clear, but calming their nerves around the FDA through rapid reforms, improving tax policy, and wringing more uncertainty out of the payor market are all important. We also need more steak and less sizzle in the promotion of our rising stars: over-promising and under-delivering has been a hallmark of biotech companies for years and has earned us the scorn of the public markets.

With regard to the lack of company formation, we’ve heard for years about the reduction in early stage biotech venture capital, and its certainly true the landscape has changed. As I’ve noted before, when we’re looking to syndicate our early stage deals, corporate VCs are some of the first folks we call – a striking difference from five years ago. And there’s certainly been a challenging environment to get early stage deals done, but a large number of promising startups still get financed. According to VentureSource, 545 first round financings were closed in the U.S. between 2005 and today. Not to mention the pre-existing universe of private biotech companies, probably more than doubling that number. That’s at least 4x the number of public biopharma companies. Now many of these will fail to deliver anything, and many more will deliver less than exciting or relevant products, but that’s certainly not for a lack of trying. Do we need even more innovative new startups? Sure, and there’s a bunch of us trying to help create those new companies.

Lastly, the mega-mergers and big acquisitions have certainly left us without the diversity of big firms we once had: Genentech, Genzyme, Wyeth, etc have all become names in history books. This trend certainly contributes to the shrinking number of big players competing for deals, and effects the ecosystem significantly, but it doesn’t fundamentally move the statistics above. The acquisitions of the small and mid-cap players are important for driving the liquidity that gets recycled to fund new startups and the expansion of emerging ones. As an investor, I’d like to see more rather than less on the acquisition front frankly, especially since there are no other attractive liquidity paths right now.

We should all be concerned about the shrinking state of the biopharma ecosystem. The major issue from my vantage point is that for most of the past decade there’s been no real access to public market sources of the low cost-of-capital financing required for building and scaling biopharma companies. This has lead us to pursue other business models and experiments on the startup front, involving closer ties to larger players, and we’re confident some of these will create real value. This type of adaptation is important if not critical in this environment; but we also need to figure out how to restore access to attractive growth capital for the long term health of the sector.