Doing more with less, hanging on to fight the next fight, putting out fires on multiple fronts are all de rigueur here at the Atlas Venture NewCo factory (aptly coined by brother-in-arms, @michael_gilman). Our seed model (here, here) focuses on early technology validation, usually demonstrating preclinical proof-of-principle, prior to scaling up a full-time team and Series A to advance the company to the next value creation point. The early science is executed by small, multi-tasking management teams, often in partnership with CROs and/or academic labs who have the expertise for efficient, cost-effective achievement of the seed objectives. Getting it right the first time is imperative given limited funding and short timelines.

The daily toil of a start-up venture can often feel like a battle. So is there a management framework one can draw on to manage lean R&D teams and CRO partners through early technology validation and beyond? It turns out the 19th century Prussian army offers prescient guidance on how to lead from the start-up trenches.

The 18th century Prussian military was composed of highly-trained automatons who thrived under traditional, top-down leadership. However, the army’s dominance unraveled as war evolved into more fluid, technology-driven engagements. Quick decision making in the face of rapidly changing conditions provided advantages to nimble, de-centralized armies that could not be achieved by large, hierarchical ones. In 1832, Carl von Clausewitz debuted On War as the preeminent tome for creating and leading a more nimble military.

Clausewitz and his contemporaries realized that a battle plan, no matter how thoughtful and comprehensive, does not survive the first engagement with the enemy and the inevitable chaos that ensues. A different leadership architecture was required to align the army to the overall mission, yet also provide the flexibility for leaders down the chain of command to adapt and take calculated risks based on the evolving situation on the ground. This was the birth of Mission Command leadership, which is now commonplace in the 21st century NATO and US armed forces.

Enter Stephen Bungay, a unique breed of Oxford-trained military historian and former 20-year vet of the Boston Consulting Group. Bungay recognized some similarities (and many important differences!) between the challenges facing Clausewitz’s army and those in the global businesses at the center of his management consulting practice. Companies operating in today’s environment are surrounded by what he and Clausewitz call “friction” – the ever-present complexity derived from the fact that organizations are run by humans. We all have limited knowledge due to the imperfect nature of information, an inability to predict the future, and independent will driving our decisions. Human nature creates “friction” when we collaborate within organizations, as well as when organizations interact with one another.

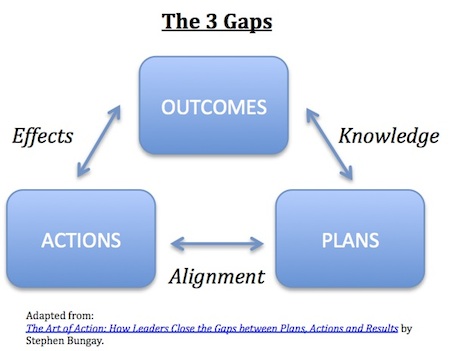

In his book, The Art of Action: How Leaders Close the Gaps between Plans, Actions and Results, Bungay outlines three quintessential gaps that friction creates between plans, actions and outcomes:

- Knowledge is the ever-present difference between what we know and what we would like to know. This gap prevents us from creating plans that result in perfect outcomes.

- Alignment spans the gap between what we would like people to do and what they actually do, a reality that cannot be overcome by even the most ardent top-down management.

- Effects concern the gap between what we hope our actions will achieve and the fact our hopes rarely align with what transpires – we conduct our R&D through experiments for which we don’t know the outcome.

Common reactions to addressing these gaps – seek more knowledge before making a decision, micromanage to achieve alignment or desired effects – not only don’t address the problems, but usually exacerbate them. These are among the management challenges that Bungay was being called on to fix.

As a solution, Bungay outlines an incredibly simple, yet not entirely intuitive framework:

1) Decide what really matters – Don’t attempt to create perfect plans that exceed the limits of what is knowable. “Instead, use the knowledge which is accessible to you to work out the outcomes you really want the organization to achieve.”

2) Get the message across – Share information clearly. “Keep it simple. Don’t tell people what to do and how to do it. Instead, be as clear as you can about your intentions. Say what you want people to achieve and, above all tell them why.”

3) Give people space and support – Don’t micromanage. “Encourage people to adapt their actions to realize the overall intention as they observe what is actually happening. Give them boundaries which are broad enough to take decisions for themselves and act on them.”

While Bungay applied this “directed opportunism” framework to Pfizer and other large multinational organizations, I have found it incredibly useful for managing biopharma start-ups.

Let’s look at an example of this framework in action – NewCo X has a stated mission of advancing its a lead-stage small molecule program through human proof-of-concept (or beyond) to maximize the exit value of the organization. Capturing what matters in a simple statement, which should be agreed by the company’s board and senior leadership at inception, frames the organization’s intent – the what and the why.

Next up is empowering the team to execute in their respective areas of expertise. Start-up management teams and boards are often (although, not always!) composed of bright, talented folks who are used to executing in the uncertain world of pharmaceutical R&D.

Regardless, the board and the CEO should convey as simply as possible the company’s intent and the role each senior leader will play in helping to make it a reality. Getting this message across clearly is particularly important as team members often work remotely and in collaboration with global CRO’s and consultants. A clear statement of intent, transparent information sharing, and effective two-way communication will help increase the likelihood of success. The choice of team members is critical, indeed Clausewitz deliberately chose officers who had infringed the Prussian Army regulations, because they were more likely to adapt in the face of a dying battle plan.

The rest is really just good management practice to help minimize the alignment gap. Frequent check-ins at weekly team meetings and in teleconferences with CRO partners are imperative to share new information. Team members should also be given leeway to flex outside their core competencies to help fill in the inevitable white space around any early stage scientific venture. Fostering personal relationships through team dinners, Sox games, and other outings goes along way to ensuring everyone is performing in concert. Regular get-togethers also apply for remote consultants and CRO partners – quarterly or biannual face-to-face meetings are essential to renewing alignment around the organization’s intent – what are they trying to do and why – and each person’s role in helping achieve it.

The concepts espoused by Clausewitz and Bungay essentially empower people to collaborate effectively to achieve a common goal in the face of a complex, rapidly changing environment. The framework’s utility can easily be overlooked due its simplicity. Of course, issues still arise, as we can never escape from the inherent friction of being human. However, I have yet to come across a more practical and relevant construct for running small biotech companies in the vast management consulting literature.