How many new biotechs should the industry be starting per year? It’s a perennially asked question, and obviously not one with an easy and straightforward answer.

On the one hand, if you believe only transformational new ideas should get funding, the number should be fairly low as breakthroughs don’t come around every day. But, broadly speaking, we aren’t great at predicting transformational impacts, so one could argue more is always better – and the stochastic and Darwinian nature of science and life will eliminate those “bad” (less good) ideas.

Most pundits and industry observers would probably agree with the latter, and lament the perceived low rate of startup formation. Their common refrain goes something like this: VCs and other investors aren’t funding enough new startups, tons of great new ideas aren’t being invested in, lots of these potential therapies are therefore dying before they see the light of day, if we only had more money and more startups we’d have lots more successful and impactful medical innovations, and return on investment will follow.

I’m doubtful that refrain is at all accurate, especially about the “returns will follow” piece. There’s also not a dearth of startups by historic measures: roughly ~100 new biotech startups get formed, financed, and reported for the first time by VCs every year. I add “reported” because VC-led seed financings that don’t pan out never get included in the data. Take those VC-backed first financings, and add on the several hundred angel-backed (and now crowdfunded) biotechs, and I think its fair to say there’s a lot of new company formation going on. Would it be great if there were 10% or even 30% more startups in a given year, sure – especially if we’re all practicing an optimized version of the “kill the losers” approach to investing in biotech. But doubling or tripling the number of startups doesn’t make sense for several reasons.

First, I’m not unconvinced there really are 100 new transformational medical ideas worth funding each year. That’s a breakthrough every 3 days. I read the occasional science paper, as do my colleagues, and we have yet to come across that frequency of breakthrough ideas. Dozens of good ideas for new therapeis a year seems reasonable, not 100s of good ideas.

Second, too many biotech startups imply a big waste of resources: lots of money spent chasing false positives, time and talent wasted working on those ideas, and importantly, large ethical concerns around enrolling scarce patients in clinical trials with little hope of succeeding, sacking excessive numbers of animals for preclinical models that don’t mean anything, etc… Lemming behavior in VCs would also push for the therapeutic equivalent of dozens of VCR technologies chasing the same goal.

As a counterpoint, too few startups is also a bad thing: without a big enough pool of ideas and teams getting funded, we aren’t preparing the sector for serendipitous positive and negative outcomes, and presumably lots of good (and possibly great) ideas aren’t able to move forward.

The answer, then, to the question of how many is the right numbers is obviously somewhere in between those views– a Goldilocks number of startups that’s neither too many or too few.

To inject some data into the discussion, its worth reviewing how the sector is doing today, especially since less than two years ago pundits were lamenting the life science’s dearth of new startups, citing the “lowest rate of startup formation” since 1996.

Fortunately, things do look better and in many ways the sector’s rate of startup formation may have reverted to the long term mean, or be on its way there. Here’s a deeper look at the data from Thomson Reuters on “first financings” of biotech.

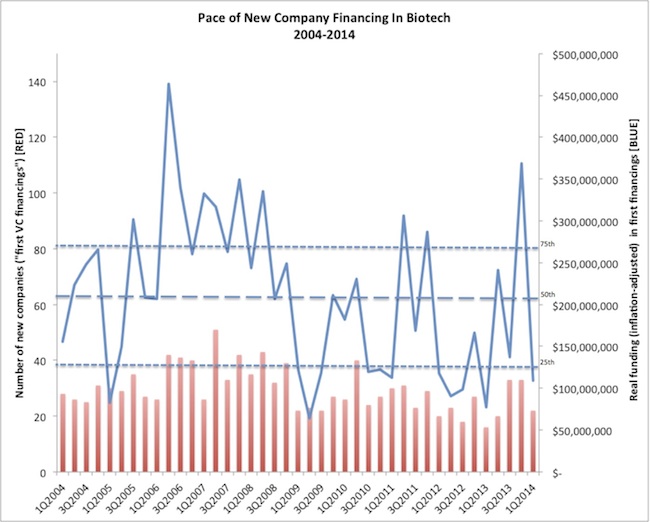

- Funding levels for first financings: While it looked pretty dire in 2012, the past few quarters have picked up; despite some lumpiness, we had one of the biggest quarters of all time at the end of last year, and the last twelve months are back to the 10-year inflation-adjusted average (real figures, 2013 dollars, Blue lines in Figure 1)

- Number of VC-backed startups: we’re running as a sector within 10% of the last decade’s average of ~30 per quarter. The second half of last year was nicely above that run rate (Red columns in Figure 1)

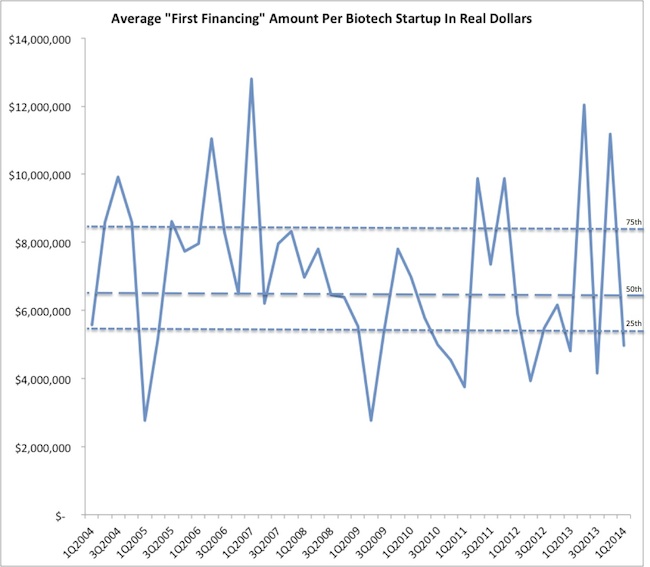

- Funding per startup: This number is about 15% higher than the long-term mean (Figure 2), now around $8M per company. Based on our own experience with seed funding and tranching, $8M is presumably the first 18-24 months for many early stage companies – even those with bigger “headline” numbers typically have first tranches in this ballpark

Statistically, I’d argue that all of these figures are now back to the long-term average and in the noise of characteristically lumpy quarter-by-quarter data.

Reflecting on the go-forward dynamics of startup creation, here’s my take on the three main ingredients required:

- Great science with big potential medical impact. I’m confident that we are in one of the best periods ever regarding the quality of the biomedical science and its potential translatability into therapeutics. Despite the reproducibility challenge, the substrate pool is deep and the ideas that float to the top are highly backable by investors. We’ve started a dozen or more drug discovery plays in the past couple years around this great substrate. It’s what gets us all excited about the field today.

- Talented entrepreneurs to help found, build, and scale new drug R&D startups. I’ve blogged about this in the past – today we’ve got a great influx of R&D talent into biotech from bigger Pharma companies. While a long-term challenge, in the near-term this abundance of R&D veterans looking into biotech has been a boon for startups. That said, talented C-level executives in biotech remain (like always) the critical challenge: great CEOs are hard to find. But this is not new news, its always been the case.

- Risk capital to fund startup R&D plans. Based on the data above, even in an inflation-adjusted sense, there’s been a relatively steady flow of capital over the past decade into “first financings” of new biotechs, even with the blip of 2012’s slowdown. Further, a large number of LS-only or LS-diversified venture firms are back out raising new funds – and rumor has it some large closings will happen in the second half of 2014.

So, in short, it’s a great time for starting new companies – the science, people, and capital needed to do this are all positive forces for the sector.

Will we get back to the 140 or so new startups a year, as it was in the “boom” of 2006-2008? Not sure, and not sure whether that would be good: it depends on the mix of companies being formed. One big difference from those “boom years” is that we are seeing far fewer “specialty pharma” deals being created around reformulated drugs or repositioned older active ingredients. The message that “innovation pays” has clearly been embraced by the bulk of the ecosystem. Even shops biased to later stage deals have recently placed “riskier” early stage bets on novel approaches – RNAi at VenBio (Solstice), microRNA with Sofinnova (Mirna), etc…

Lastly, the temporal lag from founding to IPO is worth reflecting upon. The median time from first funding to an IPO in biotech, according to the NVCA, was 7.5 years in 2013, up slightly from the past couple years. Of the nearly ~70 therapeutic biotech IPOs since January 2013, spanning founding dates from 1990 through 2010, nearly one-third of them were founded during the three-year period of 2006-2008. That’s a significant enrichment in the sample set. Those “boom years” of NewCo formation, during which time over 450 biotechs got their first financings, clearly fed a disproportionate amount of substrate relative to other vintages into the 2013-2014 IPO window. These 6-8 year old companies were maturing at just the right moment in time to get picked up by a receptive public market. In light of that, it’s interesting to speculate on the impact of the decline in new startups from 2009-2012. With 30% fewer startups, the pool of maturing companies in a few years will be smaller. The good news is those with quality biotech inventory arising during that period should be able to find outsized demand in the market. The bad news is there might not be as much maturing substrate to sustain the interest of the public markets and the appetite of bigger drug companies.

Time will tell whether we get the Goldilocks number right or not, but in the meantime its good to see innovation-rich startups getting launched at a good clip.