The world is awash in cool new tech startups and poised for “A Cambrian Moment”, according to a recent special report from the Economist. For those that haven’t read it, it’s a very interesting set of articles about the trends shaping venture formation in digital media and software: the ease of starting new companies, the proliferation of accelerators, better and more transparent markets for funding like that created by AngelList, the platformization of everything, etc…

But in some ways I was more intrigued by a critical review the Economist recently posted by Daniel Isenberg where he focuses more on the “startup glut” in technology and digital media, and in particular the challenge of scaling a business when the “on-ramp” for emerging companies is so congested.

With huge winners achieving massive scale, like Alibaba and its pending IPO, Facebook, and Twitter, it’s easy to see why there’s a rush to create the next big one. Barriers to entry are nearly zero in many cases, and speeds of product iteration are incredibly fast. This has led to the startup glut that Isenberg and many other pundits refer to – tons of startups, hyper-competitive product markets, but irrational group-think optimism around “everything is awesome”.

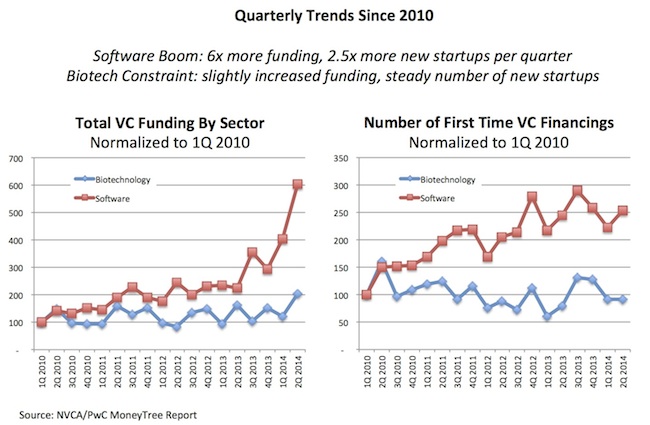

The nature of this evolving and exploding Tech market is in striking contrast to Biotech, where the rate of funding and new company formation have been remarkably steady for years (most of the last dozen years since the Genomics Bubble burst).

Here’s a snapshot of comparing the normalized levels of overall VC funding as well as the number of newly-backed startups (using the NVCA/PwC Moneytree data around “First Financings” as a proxy) in software and biotech:

While biotech has been relatively constant on these funding and startup metrics, software has experienced a massive boom. Tons of money is flowing in, and huge numbers of new startups are forming.

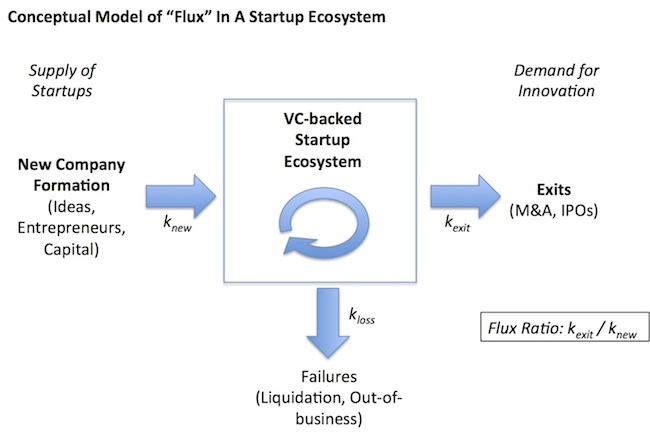

This dichotomy got me thinking about the relative “flux” through the two venture ecosystems. Here’s the conceptual model: on one side, we have the supply of new startups – entrepreneurs, ideas, and capital coming together to create new ventures. These flow into the ecosystem, and either succeed in growing, raising further capital, and creating something innovative enough that others will value, or they fail and go out of business. If successful at creating something of value, this demand creates “exit” events as they depart the “venture” ecosystem – either IPOs where companies attract new investors to help them scale, or M&A events where they get integrated into larger businesses. This balance of the supply and demand creates the equilibrium present in the venture ecosystem around a sector, as depicted in the figure below, and directly shapes the aggregate returns of the sector in the asset class.

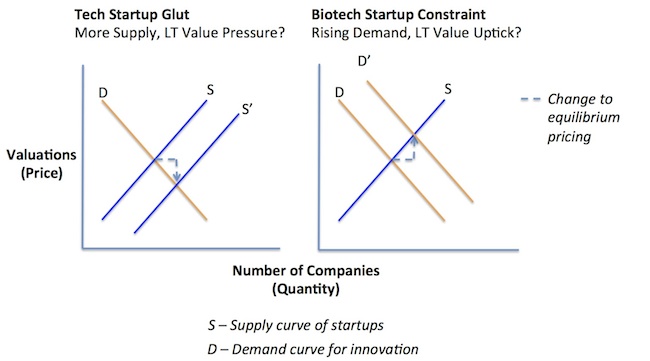

As a biochemist, I didn’t get much past ECON-101, but supply and demand curves made sense to me, and what changes or imbalances can do to markets and sectors. Understanding how the respective supply of startups and exits has changed over the past few years should help better understand the future – and give a sense for the relative trends around the attractiveness of sectors to venture investments.

Biotech as an investment sector has improved dramatically in recent years: it’s a supply-constrained startup market with strengthened intrinsic demand. As the data above suggests, the supply of new startups and funding has been largely constant (S). But it’s also clear that the demand for biotech innovation has gone up both in terms of the continued expansion of the IPO market and robust BioPharma acquisitions of VC-backed biotechs (shift from D to D’). In contrast, at least at the macro level, software as a market has gone the other way: a massive proliferation in the supply of startups and funding (S to S’), but relatively steady demand by the M&A and IPO markets over the past five years (D) (see NVCA Yearbook for data).

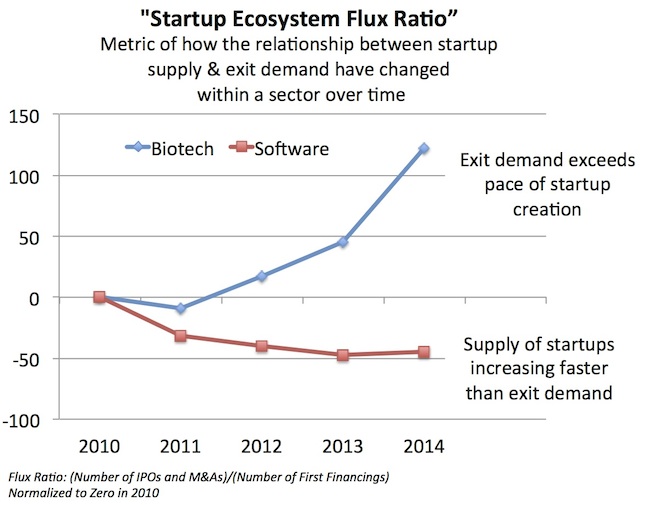

Is there any way to quantify this trend? Probably not in a robust manner, but a directional measure would be to look at what I’ll call the “Startup Ecosystem Flux Ratio”, or kexit/knew, calculated simply as the number of exit events (M&A, IPO from NVCA data) vs number of new VC-backed startups (using the NVCA/PwC MoneyTree metric of “First Financings” as a proxy) in any given period of time. While the absolute numbers are largely meaningless, the change over time in a given sector sheds light on how the supply/demand balance is shifting – so I’ve chosen to normalize both sectors’ flux ratio to zero in 2010.

The results quantify the striking shift: innovation-rich biotech has been becoming a far more attractive sector to invest, where long term price equilibrium would be predicted to go up. Indeed, simply looking at valuations in the recent IPO window and mezzanine financing market suggest this chart is clearly directionally correct.

Importantly, this is not meant to compare the relative current attractiveness of Biotech vs Tech, but merely understand the trends within each of those sectors over the past few years. At the market level, this analysis says Software has gotten or will get tougher to pick winners. With rates of new Tech startups vastly outpacing exits (knew>>>kexit), it suggests one of three things has to happen. Exit demand could pick up and balance the equilibrium, but more likely is either that the Tech ecosystem expansion will continue or that the aggregate loss ratios in software will have to go up (more companies will fail to generate good returns). I suspect some of both of the latter will occur, but only time will tell. Bubbles on the supply side will either burst, or they will alter the steady state equilibrium of supply/demand for new companies and their innovations.

Back to Biotech: a few questions arise from these observations, all of which deserve entire blogs on their own:

Why is biotech startup supply so constrained? First, there aren’t dozens of breakthrough biomedical ideas created every day; while substrate for startups is very rich, figuring out which are likely translate successfully into high impact medicines diminishes the viable number of big, attractive ideas quickly. Second, there are very few biotech venture investors still active today, and fewer still that are focused on early stage company creation. Third, and of critical importance, it’s not easy to start biotech companies, and in most cases requires entrepreneurs with decades of apprenticeship inside larger R&D organizations – navigating the drug discovery and early development process requires experience well beyond simply advanced degrees (MD/PhD). Seasoned veterans willing to take startup risks are relatively rare and highly sought after. A 40-something (or older) entrepreneur with kids (responsibilities) and a solid corporate career is a very different animal than a 20-something in flipflops that likes to code along many dimensions – risk-taking, salaries, culture, type of coffee they like, etc. These three forces all conspire to constrain the number of new startups by keeping the frictional startup costs and barriers to entry relatively high.

Why has the demand for biotech innovation been so strong? A variety of reasons. Beyond the macro support for booming global healthcare demand, the two big buyers of equity from emerging VC-backed biotechs, the public market buyside and Big BioPharma, are both as strong as they’ve ever been. The broader biotech public markets have done well, and driven further demand for new issuances (IPOs), as discussed here in 2013 (the drivers all continue today). The public market has also matured: dozens of biotechs have now launched products and become commercial entities (PCYC, REGN, INCY, NPSP, etc). And the second big buyer, Big BioPharma, continues to source a significant portion of its pipeline externally (>>50%), in particular from venture-backed biotechs.

What’s likely to be the trends going forward? This is, of course, the billion-dollar-question. Rates of supply (new startup formation) in biotech aren’t likely to increase dramatically anytime soon, as none of the three contributors listed above are easily expanded. After the culling of the venture lemming-herd over the past decade, LP’s appear to be taking a renewed interest in backing Life Science VCs, but this will take years to make a big impact on the sector’s startup fund flows. On the other side, I don’t believe that demand for new, high impact medical innovation – which will feed Pharma pipelines eventually – is also likely to reduce over time. In short, intrinsic factors around the nature of innovation favor continued strong demand forces.

So as you might expect, I’m bullish on the long-term equilibrium favoring the continued (and increasing) attractiveness of Biotech as a sector in the venture asset class: tightly-funded and supply-constrained, with exit demand outpacing investments, Biotech has the right macro fundamentals to be a good place to be investing.

Against that backdrop, we’re excited to be focused here at Atlas on increasing the supply of high impact, innovative biotech startups.