Venture capital investing in biotech has long been hard to disaggregate: how much goes to “early stage” vs “late stage”, how much goes to CNS vs oncology, discovery vs Phase 3, etc…

Today BIO’s David Thomas and Chad Wessel have put some much-needed light onto the biotech investor trends over the past decade with a newly released report (here).

Before highlighting the conclusions, a quick note on their data-driven approach: their aim was to build a more comprehensive view of how and where dollars have flowed in therapeutic-directed venture capital. To do so, they created their own database, including more than 1200 US drug companies receiving over 2000 rounds of financing during 2004-2013. This dataset was assembled this out of four other databases (BioCentury’s BCIQ, Elsevier’s Strategic Transactions Database, EvaluatePharma, and Thomson Reuters’ ThomsonOne), and curated that further with inputs from media reports, SEC filings, etc… Like all datasets, the authors use some simplifying assumptions of when to include/exclude specific financings. Overall, having seen this work come together last fall, I am confident they’ve assembled one of the most well-curated datasets on the subject.

The report lays out a set of interesting conclusions, in particular around disease level funding, but I’d like to call attention to four of them here (highlighting my bias towards the early stage conclusions):

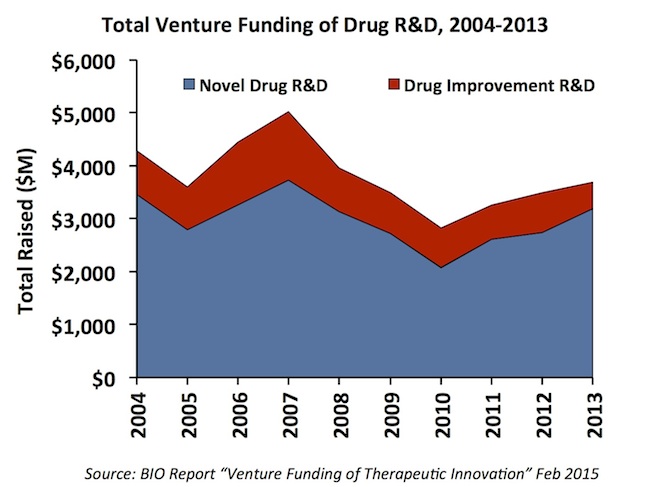

First, over the past decade, nearly 80% of venture capital for therapeutics went toward “novel drug R&D” rather than improvements on existing drugs (e.g., new formulations, repurposing, drug delivery, etc…). New chemical or biological entities have become the primary interest of venture capital investors, and this has modestly increased over time. This trend is in contrast to the rise of “low technical risk” spec pharma investment model of the 2001-2007 period. The chart below captures the trend in both types of venture funding

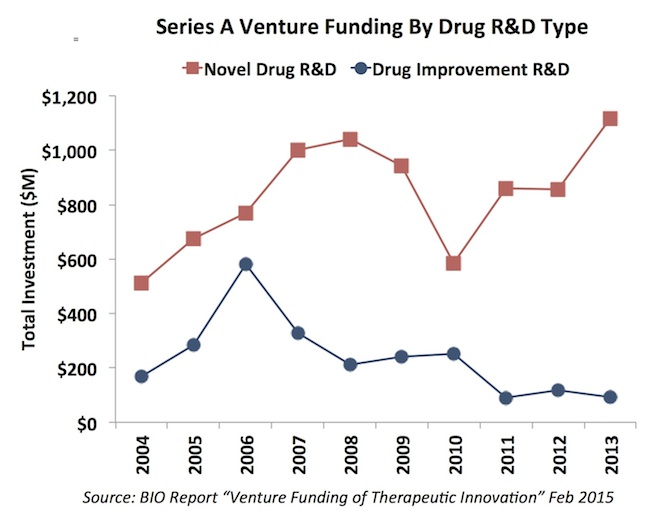

Second, initial rounds of funding (Series As) for novel drug R&D reached their highest levels in a decade in 2013. The importance of “high innovation quotient” investment thesis to gather initial venture funding is clearly on the rise. This is a healthy trend for our industry as a whole – focused on more impactful R&D projects. I suspect the 2014 data will continue that trend.

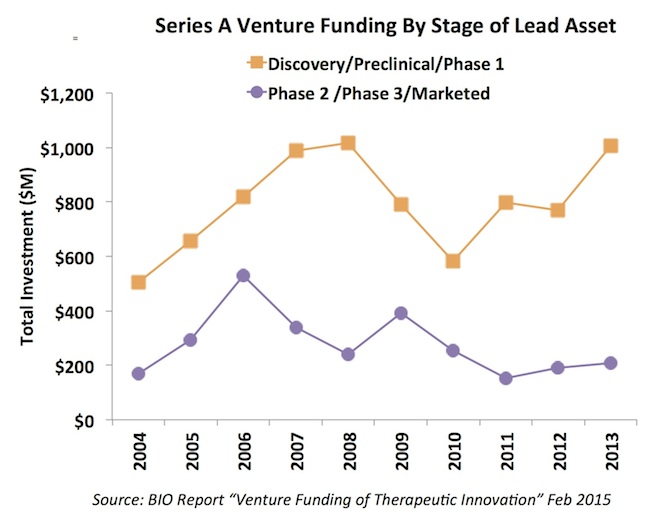

Third, most of the Series A funding of new startups has gone toward early stage assets (drug discovery, preclinical, and Phase 1), and this has increased over the past five years. Further, the majority of the early stage financings went to discovery/preclinical (~75%) vs Phase 1. The oft-heard phrase from entrepreneurs raising capital that you need clinical data to attract a venture capitalist is simply not borne out by these data; in fact, they question in some ways the widely held view of the “valley of death” facing early stage technologies as they move out of academia.

Fourth, these data highlight that the pace of startup creation hasn’t changed in the past five years. This further confirms the relative inelasticity of the supply of new startups in the face of significant demand for innovation. This is a theme I’ve written on several times in the recent past (here, here), as I see it as a major structural feature to our industry today.

Lastly, there were several other themes highlighted by the data that I’ll mark off here:

- Biologics investing has steadily increased as a share of venture funding versus conventional small molecules, reaching 50% of the funding in 2013, its highest level in the dataset. These large molecule biologics include antibodies and protein therapeutics, but also RNA and gene-based therapies.

- Platform companies – or more aptly called drug discovery engines capable of making drugs in lots of different disease areas – saw a modest uptick over the last decade. This is in contrast to the negative sentiment in the middle of the 2000s.

- The bulk of the report goes into specific disease area funding levels. Several big primary care diseases like diabetes/endocrine and cardiovascular have seen significant reduction in their allocation of venture capital since 2009 (versus the prior five years), whereas specialty diseases like ophthomology and orphans have increased their allocation over time.

I would note a point of statistical caution regarding detailed disease-specific conclusions in the report: as the data gets cut down into disease categories across individual years, the resolution in the data becomes more noisy and challenging (e.g., with the impact of lumpy and tranched financings common in venture). The authors chose to use the five-year convention of 2003-2008 and 2009-2013 as a way of broadening the sample sets. An alternative would be to use multi-year rolling averages, but having looked at that cut of the data it doesn’t dramatically alter any of the major conclusions.

A big thank you to the team at BIO that supported this important work – it adds a valuable piece of insight and transparency to the private biotech investing world.