It’s all about people, it always is.

Human capital is a company’s most important asset. Successful companies have human capital management strategies that excel at talent recruitment, and prioritize career development and retention.

But human capital is never static, and change is an important part of talent management in an organization. Changes in leadership often increase executive entropy, with both positive and negative consequences. For instance, a new head of R&D often precipitates a series of both voluntary and forced departures, and the important new additions, that change the composition and dynamic of leadership teams. This is all part of the natural evolution of organizations (both directed and more random).

High-performing teams often bring a mix of individuals with past experiences of different corporate cultures, normative behaviors, and approaches to managing both risk mitigation and resource allocation.

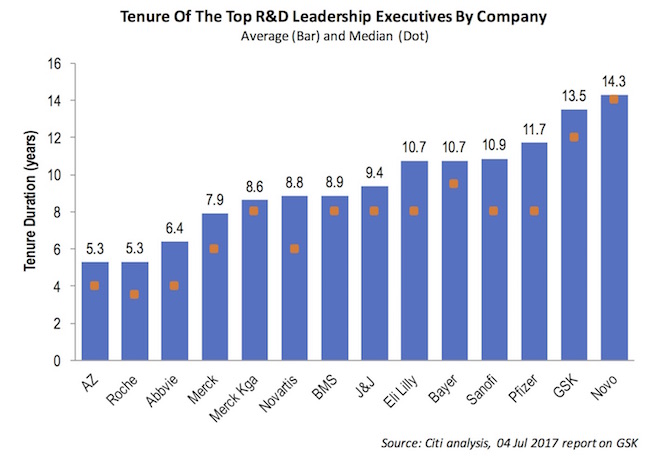

With this context in mind, I was struck by a thought-provoking recent analysis of Big Pharma by Citi analyst Andrew Baum and his team. They looked at the average and median tenure of the top 20-30 R&D executives across set of large Pharma companies. Below are the data (thanks to the team at Citi for sharing).

This benchmarking chart was presented in the context of Citi’s comprehensive report on GSK in July 2017, and the authors suggested that an R&D overhaul of GSK should focus on bringing some new blood into the organization.

Beyond highlighting GSK’s position at the long-tenured end of the spectrum, it also demonstrated the quite wide range of tenures across the industry: average leadership team tenures spanned from 5 to 14 years, a huge difference in institutional history.

What’s the right average or median tenure for a leadership team? It’s certainly not one number: the “right” metric for average tenure probably depends a lot on the organization, and on what the historic performance of the team has been. Frequently, the most productive R&D organizations are those that embrace externally-sourced leadership talent as a complement internally-developed leaders. External talent is especially important when productivity has lagged in the past, or when pressed with a “burning platform” for change.

But at steady state, I think a healthy R&D leadership team has a blend of newcomers from outside and internal leaders, which implies the optimal average team tenure should be 6-8 years. The median should be several years lower than that, since tenured 20+ year “lifers”, the old guard so to speak, will drag the average up when mixed with newcomers. Organizations with average tenures on the shorter end of this spectrum often reflect those with more recent dramatic changes (e.g., like AZ’s near-complete rebooting of R&D or Merck’s reorg after Roger Perlmutter arrived, both beginning in 2013).

Because every situation is different, I’m not sure R&D productivity itself correlates tightly with average tenure of the R&D team in the chart above. But there’s probably some direction signal around the correlation for some of the companies benchmarked above – so injecting new external talent may be a worthwhile aspiration for a number of them.

Importantly, tenure and R&D experience aren’t the same thing. Experience results from the accumulation of different roles and opportunities that create the softer learnings leading to better judgement, risk-assessment, and pattern-recognition when it comes to R&D portfolios and projects. Tenure, in this context, is about the length of time working through roles in the same organization – exposed largely to the same cultural frameworks and institutional biases over that period.

While “experienced” teams are almost always a virtue in drug R&D (and in startups, too), teams with long-dated tenures within a single corporate environment often exhibit counter-productive characteristics. Overly-tenured leadership groups can ossify the organization around stale mental models and worn-out approaches. Teams with high intrinsic tenures often default instinctually to the well-established norms, aka “the way we always do it”. This default state often makes it challenging to take advantage of potential opportunities to think creatively, break the mold, and catalyze out-of-the-box innovation. “We don’t do cell [or gene] therapy” was a common defaulting refrain from R&D executives several years ago; I suspect many are reconsidering this today – much the same way Pharma’s chemistry-led shops viewed antibodies two decades ago.

With its long timelines and multi-disciplinary inputs, it’s easy to fall back on the “established” process of how things have historically been done. Further, the decision labyrinth for moving/killing projects often obfuscates downstream accountability – and without accountability it’s easy to ride out a long-tenured career with little personal responsibility for failed decisions. It’s just too easy to rely on the precedent and usually over-burdened governance model of large organizations where everyone falls into line around “the way we always do it”.

Every company also develops its own lingo or jargon for the stages and goalposts of R&D, creating a nearly impenetrable set of acronyms and committee names. Long-tenured individuals become de facto gatekeepers to the decoder ring of these corporate dialects. Corporate-speak and use of the latest buzzwords by this group create a veneer of innovative thinking, but these are often just cosmetic covers on top of deep-seated, often-dogmatic ways of managing R&D. All of these conspire to reinforce a “status quo” mental model, which rarely tolerates a clean-sheet-of-paper fresh perspective on how to do things differently. In this world, the negative impact of tenure is profound.

Of course, there are positive aspects to tenure, too. Projects live for years in R&D – progressing from discovery to approval (if they are successful) over a decade in many cases. Tenure helps provide project continuity and perspective. And, despite the comments above, being around when the data shows up years after the decisions are made does enable real accountability (though rarely done in practice). In addition, taken to extreme, fast career development cycle times across many companies (jumping every 3 years to a new job) is never a good sign.

Is there an optimal tenure for an executive in one organization? Again, as above, probably not. Depends on the individual, their personality, and the opportunities that avail themselves. But, at the risk of over generalizing, I think there’s something to the “seven year itch” in a professional sense. Tenures in the 7-10 year range allow one to make deep meaningful contributions, but still maintain a fresh view. Plus, with that cadence of corporate change, over a single career one can witness, participate, shape, and benefit from multiple professional environments.

As a final thought, it’s worth emphasizing how leadership teams form and function. Team development, from the soccer field to the boardroom, is always important. Many teams go through variants of the “forming, storming, norming, and performing” model of team development; as a result, the team possesses a shared sense of ownership of the goals, a tolerance for different views, and a high-performing ethos.

But this model of development often only happens when teams are formed together. The reality of executive leadership teams in big established companies is more gradual. They don’t often follow this model because teams just don’t appear at the start, they are gradually changed over time with departures and additions affecting the team’s overall composition (e.g., adding a new head of clinical, new discovery chemistry lead, or therapeutic area head). This often makes it harder to establish truly new behaviors, processes, and systems of team governance, and leads to affirmations of the traditional hierarchy and defaulting back to “the way it’s been done before”.

In contrast, startup teams often (almost always) go through the crucible of the forming-storming-norming-performing process. While pre-existing relationships in the team are not uncommon, every startup management team forms anew in the first year or two of a startup. Every NewCo launch is a new chance to approach the way teams function and decisions are made with a clean-sheet-of-paper. Startup team behaviors don’t suffer from the status quo (as much) because in the early years things are incredibly dynamic. Storming happens a lot, and reappears as new personalities learn to work together. The newness of the team dynamic doesn’t mean everything is perfectly efficient or smoothly fluid early on – quite the contrary in many cases – but the team gets to define the norms rather than inherit an ossified framework.

Lastly, new blood in an organization brings new ways of doing things, and can revitalize a team. As is popular in age research today, it seems young blood stimulates more youthfulness in the aged (at least in mice). Perhaps what long-tenured Pharma teams need to do is figure out how to create “organizational parabiosis” models, infusing the less-tenured new blood of experienced startup executives into their corporate veins. Mixing individuals of different large and small company experiences is as valuable as simple tenure differences. Actively encouraging the cultivation of external profiles in annual succession planning amongst leadership teams is certainly worthwhile. How many Pharma’s have multiple former startup biotech executives in their R&D leadership ranks? Very few, I suspect. Perhaps there’s a learning in that observation, and a need to change it.