By Aimee Raleigh, Principal at Atlas Venture, as part of the From The Trenches feature of LifeSciVC

From the outside, one might assume all biotech venture capital (VC) firms are more similar than different. However, once you look under the hood the myriad traits unique to each firm become more apparent, even for firms that may co-invest in the same companies from time to time. While not by intent, the industry can seem opaque purely because there are relatively few investors and very little is publicized about the inner workings of venture. Focusing on the U.S. VC landscape, there are ~90 biotech VC firms with assets under management (AUM) ≥ $1B (via Pitchbook) – at the end of the day that’s not a very large number, probably translating to the high hundreds to low thousands of individual biotech investors (compared to, for example, the tens of thousands of life sciences consultants in the U.S.). Through this post I hope to shed more light on the industry, and specifically early-stage biotech VC since that is my individual bias. Below are some things I think helpful for anyone new to the biotech VC world, including potential investor candidates or company founders.

There are different flavors of biotech VC. Biotech, life sciences, and healthcare VC are often used interchangeably, but there is a modestly sized “universe” of VC firms that may fall within this umbrella.

-

- The first axis on which to segment firms is focus – typically split into therapeutics, medical devices, healthcare services, and IT. Some firms will be true generalists covering many, if not all, of these categories, and others will be quite narrow in focus. Atlas Venture is among a sizeable cohort of investors that focus exclusively on therapeutics investing – given my bias the remainder of this discussion will take a therapeutics investing-focused lens.

- The second axis of differentiation is company stage at which a VC typically invests. “Early stage” often encompasses Seed- or Series A-stage deals. Investors focused on early-stage companies will likely continue to fund companies through later rounds (Series B and beyond), but may not typically invest in new opportunities beyond the Series A. Later-stage firms typically focus on deals that are Series B and beyond (including what is considered “crossover” investing to bridge to an IPO), though depending on macro conditions can also come into traditionally “early” Series A deals. Stage-agnostic investors will invest across the spectrum. So why does knowing the typical stage at which a firm invests matter? Often stage is intricately linked with valuation, maturity of the company and / or program(s), and time to value inflection (and thus potential “exit” to the public markets or to acquisition by a Pharma). Early-stage investors are typically more likely to play some role in company formation or company building, given they may be some of the first money in and can help to play a key role in informing a company’s strategy. Later-stage investors may still take an active role, but are typically investing when more of the team and strategy has been (at least initially) built out and the thesis has been partially de-risked.

- Another axis is business model. Is the company platform- or asset-centric, or a mix of both? Ultimately every successful therapy that makes it to patients is an individual asset, so at some point even platform companies can shift to an asset focus. Some investors are strict in the types of companies they invest in (e.g., only focusing on single-asset theses or requiring a platform to de-risk the potential that any one asset fails). Understanding any investor preferences early-on is key to understanding your fit, either as a portfolio company if you are a founder or as a team member if you are a prospective candidate.

- Fund size, decision-making structure and any therapeutic area– or modality-centric investment preferences are also important to understand, though these can be harder to glean during initial diligence of a firm.

- And finally, location is not to be overlooked, especially in the context of the above. A stage-agnostic VC who may be more hands-off is likely comfortable with investments across a range of geographies, whereas company building firms may prefer to build locally.

Quick summary: If you are a potential candidate interested in a role in VC or a company founder trying to figure out how best to pitch to VCs, I strongly recommend starting with a refined list of those firms most relevant to your background, interest, company, thesis, etc. Start with an Excel of all the biotech VCs you can name, and filter by focus area, stage, business model, and location. Some of this information will be readily available on firm websites, or else can be intuited by looking at active portfolios. It’s not expected that you would be able to figure out everything, but a quick search should give you a good idea whether you (or your company) might be a good fit. And in a first call with an investor, don’t be shy about asking for specifics! Each firm is unique in its structure and culture, which translates to differences in investment decisions and portfolio construction.

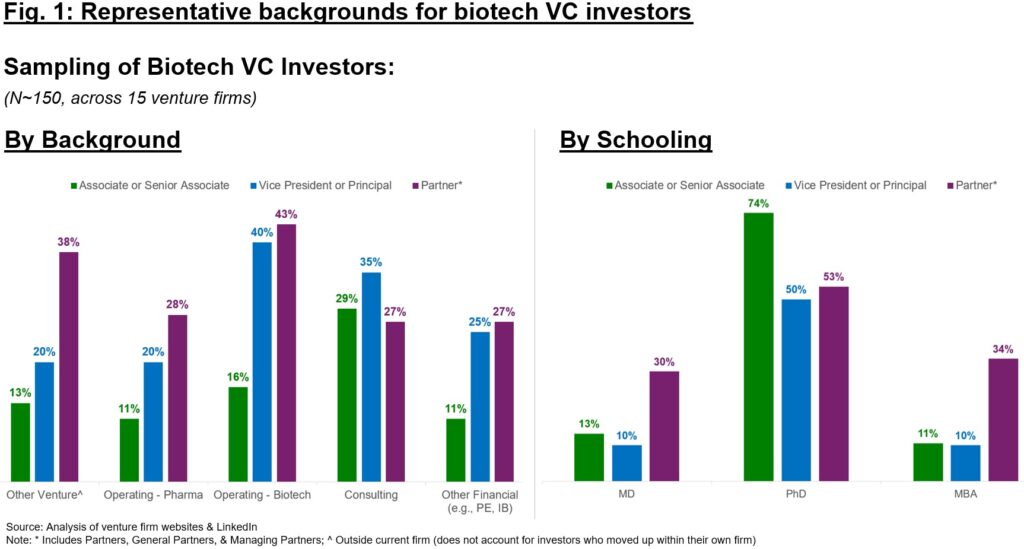

Who are the investors that make up these VC firms? Biotech venture capitalists can come from a variety of backgrounds, though several categories are most common. To illustrate the various backgrounds and relative frequency, ~150 investors across 15 firms were sampled as a representative cut of biotech VC spanning early to later-stage firms ( 1). Some notable findings from this analysis are as follows:

-

- Many VCs, even if they start at the Associate level, have some level of work experience post-schooling. At the Associate level, consulting is one of the more prevalent backgrounds, with ~30% of Associates having spent time in consulting. Operating experience (whether in Pharma or Biotech) also accounts for a substantial share, 10-15% for each. ~15% of Associates may come in with prior venture experience, and a smaller ~10% may have financial backgrounds outside venture (e.g., Private Equity, Investment Banking). For slightly more senior roles (VP and Principal), naturally more of these roles are filled by candidates who have already spent time in VC as Associates at other firms (~20%), or else they have been promoted through the ranks at their own firms. Operating experience is also much more common for VPs / Principals (by ~2x), as is other financial roles. At the partner level, experience at other VC firms is quite common (~40% of the sample), as is operating experience either in Pharma (~30%) or Biotech (~45%), while shares of Partners with either consulting or other financial backgrounds are similar (~30%).

- From an academic training perspective, many biotech investment team professionals have some type of advanced degree, though by no means is it a pre-requisite. PhD is the most common academic background (50-75% of sampling, across seniority) followed by MD and MBA (each 10-35%).

- VC can be a lifetime career, and thus unsurprisingly tenures for investors at individual funds can be quite long. In the aforementioned dataset, the average tenure of an investor at their current firm was >2 years for Associates / Sr. Associates, ~5 years for VPs / Principals, and nearly 10 years for Partners.

Quick summary: There are several entry points into VC – at the Analyst / Associate / Sr. Associate level (most typical), at the VP / Principal level, or at the Partner level. Across each, various sets of experience and background are common.

What does a “day in the life” look like? It’s a great question that is frequently asked, but the unsatisfying answer is that even for an individual investor at a focused firm, two days rarely resemble each other. VC is a dynamic and far-ranging ecosystem and thus the topics and types of activities range widely. What is universal is the 24/7 nature of VC – good news and bad news alike don’t stick to a Mon-Fri schedule, and thus much of investing is analyzing information on the fly when partial datasets are available and coming to recommendations or decisions quickly. VC can come across as a glamorous lifestyle of networking, but while making connections is certainly one aspect of the role, it is dwarfed by much of the hard work that goes into the day-to-day activities.

More “typical” activities can be broken into 3 categories (1) active diligence for new deals in the pipeline, (2) company building (if applicable – see above on early-stage VC nuances), and (3) portfolio & fund management.

- Diligence: Across firms and regardless of stage, diligence will often be a key focus for investors. An investor is introduced to a new company or even a concept (if a company has not yet been formed) and, often in collaboration with other team members, advisors, KOLs, etc. must come to a decision on whether or not to invest in the company or idea. I wrote a separate piece on exemplary diligence topics (here), which outlines some of the topics one might focus on in an initial diligence.

- Company Building: Ideas for new companies can come from entrepreneurs, academia, or emerge from in-house ideation on a new technology or product thesis. Regardless of the source for the newco, oftentimes early-stage VC shops play a role in turning an idea into a product and company. While different firms have different styles, newco creation often involves the “standard” diligence on science or asset(s), but also encompasses team building, drug discovery funnel establishment (incl. assay set-up or development), asset in-licensing, clinical trial design, partnering (with CRO/CDMOs, other biotech, TTOs, etc.), strategic elements (e.g., pipeline or indication prioritization), budgeting, establishment of a near- and long-term plan to achieve key milestones, and pitching to other investors. Not every VC firm will pursue company creation, but for those that do it is a great opportunity for investors to roll up their sleeves and serve in interim or part-time operating roles to help new companies achieve the next inflection.

- Portfolio & Fund Management: Active portfolio company management is a large part of the role, especially for more senior investors. Oftentimes an investor role comes with some type of representation on a Board of Directors, whether as a Director or Observer, and the opportunity to share perspectives with company management. A VC firm will also closely track its portfolio so that its investors (LPs, or Limited Partners) stay up to date on portfolio developments. Fundraising is a key activity (especially for Partners) and strong relationships with LPs are critical for any sustainable VC firm.

Quick summary: While no two days are the same, the ability to independently and collaboratively diligence a new company or idea is crucial to the VC skillset. Depending on the type of firm, company building and portfolio & fund management may also form a large part of an individual investor’s mandate.

How does one break into VC? Many more applicants want to break into VC than there are roles available, so it’s important to consider the volume of potential openings and logistic factors like location when assessing the odds of landing an offer. This is all highly illustrative, but if you assume the ~90 or so U.S. VCs with AUM >$1B (a good proxy for a reasonably sustainable firm that will likely hire in the future), you might estimate that roles typically open (1) when someone at the firm leaves or (2) when the firm raises a new fund and / or increases the number of investors on the team. Assuming (again, very “directionally,”) a new fund is raised every 2-5 years and there is some natural turnover especially in the more junior roles, one might estimate that 30-70 Associate (or similar) roles become available every year for biotech VC firms. Many of these roles will be focused in “hubs” (Boston, SF / Bay Area, and increasingly NY) and can be quite competitive. Below are resources and tips for those considering a role in VC.

-

- To find out about new roles, it’s important to stay on top of any publicized job postings as well as build your network so that you will hear through the grapevine when a firm is recruiting. Sometimes firms will post on their website or LinkedIn for new roles, but more often they rely on word-of-mouth recommendations and / or a recruiting firm to help source talent. If you are looking to stay on top of potential job openings, I recommend following prioritized firms on social media as well as building your network through events, informational interviews, etc. to stay on top of openings as they come up.

- Given the above numbers, you will likely want to make sure you are comfortable in your current position to give the VC job search 3-9 months, given roles become available somewhat sporadically and are often tied to a firm’s fundraising. Be prepared to wait for the right role to come up.

- Every firm is unique in its own way – breadth of investment focus, level of technical diligence, working norms, culture, etc. Do your diligence before kicking off the process to identify firms that on paper fit most with your background, career aspirations, interests, and logistical considerations. Then, while interviewing, make sure you are asking questions to assess fit and collecting input from trusted advisors or mentors on various firms. You only have one shot to make a great first impression, so set yourself up for success in your first venture role by doing your homework and assessing whether each firm is truly a place you will both add and gain value.

- Related to the above, think about a skill or perspective you have that makes you unique in some way. Oftentimes investors are looking for colleagues to (politely and judiciously) challenge opinions or look for the contrarian thesis. This differentiation can take time to build, so don’t feel like you need to rush into VC right out of academia – the industry is small, so you want your first role in VC to make a strong impression.

- Finally – if you are lucky to accept a role in VC, prepare yourself for a steep learning curve! VC is very much an apprenticeship model, so there will be a lot you can’t prepare for ahead of time. An open mind, gregarious attitude, and humility will carry you far.

At the end of the day, while the industry may seem opaque, you will find that it is comprised of incredibly motivated individuals who are (at times doggedly) passionate about improving the health prospects for patients in need. The odds of a product or a company being successful are very slim given extraordinarily low success rates of drug discovery and development – it takes a lot of humility, determination, passion, and empathy to succeed in this business. I hope this post has offered a glimpse into the fast-paced and team-oriented nature of early-stage biotech VC, and good luck to any prospective candidates!