Capital efficiency has become a mantra at Atlas, one shared by a number of other early stage biotech investors. It’s a term often repeated in discussions about building young companies, and yet it has become clear that there’s no consistent definition of what the term means.

A common perception is that capital efficiency is synonymous with tightly constrained, small amounts of investor capital – the “small ball” criticism of capital efficiency. Others think it means only ultra-lean, asset-centric, virtual companies. There’s also the perception that you can’t build something big if you are capital efficient.

Those narrow views are not how we see it at Atlas. For us, the meaning is much broader, and we believe it embodies how all early stage biotech investors and entrepreneurs should view the investing world.

Lets start with definitions.

For “normal” companies, with cash flows and “real” businesses, capital efficiency is commonly defined as a ratio of outputs generated over capital expended, or some version of this. Obviously that’s not really the metric we mean in our R&D-stage biotech business.

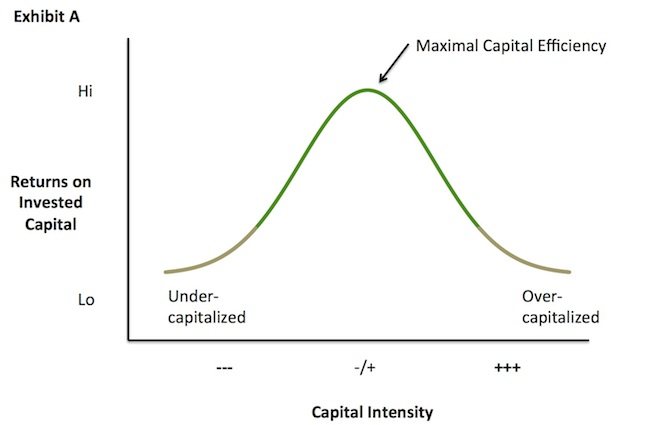

For us, the proper definition of equity capital efficiency is that sweetspot where the most amount of value is generated per unit dollar invested, as depicted in Exhibit A below. Optimal equity capital efficiency is that point on the curve where returns on invested capital for a given deal reach their peak. Over-capitalizing a company (funding it more than it needs) will result in decreased returns (the right side of the curve). Under-capitalizing a company (funding it too little) will starve a business and also result in decreased returns.

Although its very hard to know a priori what level of equity funding will generate the best returns, it is clear at company inception that different types of business models have different optimal equity capital efficiency points. Drug discovery engines, big-biology platforms will often require more equity capital; lean, asset-centric virtual entities typically far less. That said, it’s easy to miss the market and under/over-fund both of those types of companies.

To examine this in more detail, it’s worth understanding the drivers of capital efficiency.

Fundamentally, capital efficiency is a function of two major factors:

- Capital intensity, or the total amount of equity investment required to create a value inflection in a business, e.g., a drug or platform of enough value (like compelling data) to support an IPO, M&A exit, big deal, etc…). Aggregate capital intensity is clearly a function of a company’s operating “burn rate”.

- Cost-of-capital, or the rate of return new investors will demand in order to invest in a company, which is a reflection of the value created to date and projected into the future. Think of it as inversely correlating with the value per share. A business with a lower cost-of-capital has lower perceived risks and is able to raise money at better valuations. Assuming similar endgame drug values (i.e., drugs worth about the same in the distant future), a riskier biotech platform/program will have a higher cost-of-capital than a less risky one.

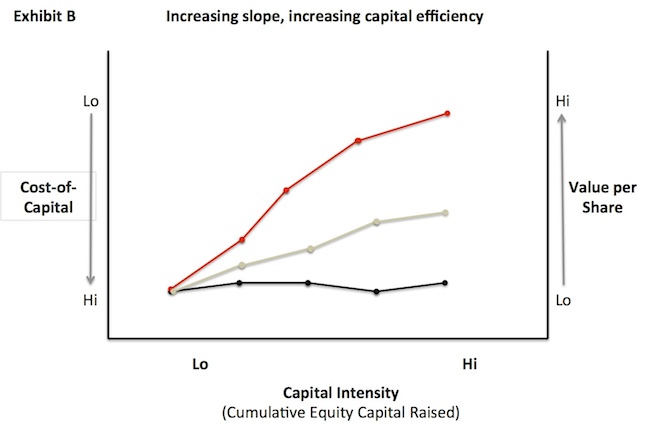

As shown in Exhibit B below, with capital intensity plotted vs. the cost-of-capital, companies that traverse lines over time with higher slopes reflect higher levels of capital efficiency. For example, the “black-line” is a biotech that raises more and more capital but does so at essentially the same high cost of capital – reflecting an inefficient use of equity capital (for the early investors, certainly). Biotechs that are able to throttle up and hit the “red-line” are ones that raise money at consistently higher valuations, thus demonstrating a nicely efficient use of equity capital along the way.

Sadly, from the genomics bubble-burst in 2001 through most of the next decade, the “black-line” archetype was more the norm. The capital intensity of biotech deals was at best uncorrelated with the value created and, at worst, inversely related to returns (certainly above ~$75M or so in venture equity) (see Figure 3 of Nature Biotech article “When Less Is More” here or this analysis by Lalande of Sante Ventures here). These data showed that the more a biotech raised in equity financing, the less likely it was to generate a stellar return. Essentially Exhibit A (above) got left-shifted for most of the decade. It was out of this environment that the mantra of capital efficiency evolved and became commonplace.

But it’s fair to say the environment for biotech has changed over the past few years, at least for the time being. Capital efficiency has been somewhat “uncoupled” from capital intensity because of a reduction in the cost-of-capital. More companies have been able to “ride the red-line” in Exhibit B. The late stage private and public equity markets are (appropriately!) rewarding earlier stage innovation with meaningful step-ups in valuation over time.

Lets take two examples.

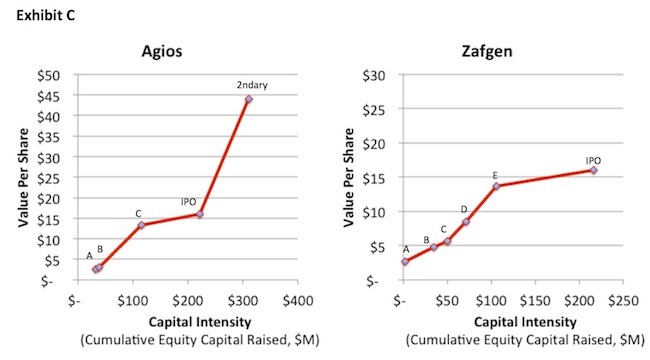

Agios is the archetypal big biology platform play, led in large part by Third Rock Ventures. They initially raised a $33M Series A round, tranched (if I’m not mistaken), at $2.73 per share (split adjusted). This created enough scientific progress to lock in a landmark Celgene deal, bringing $120M in largely non-dilutive funding (and some Series B equity). This deal drove the momentum to raise the $75M+ Series C at $13.50 per share, a handsome step-up in value, in 2011. Then it went public, raising $106M more, at $18.00 per share, and is now trading at $37 (as of this blog’s writing). If equity capital intensity was your only metric for efficiency, you’d conclude that Agios has raised ~$300M in equity and therefore must not be capital efficient. I’d argue strongly otherwise: Agios was incredibly equity capital efficient because it was able to continually improve its cost-of-capital as it ratcheted up its capital intensity.

A recent IPO from our (and TRV’s) portfolio, Zafgen, is another example, albeit of a more focused approach: Zafgen has been interrogating the role of a single pathway (metAP2) in obesity. We raised five preferred stock series before the IPO: the Series A was $2.63 per share, B was $4.74, C was $5.69, D was $8.53, E was $13.64, IPO at $16 and is trading above $18 right now. We’ve raised over $200M to date, but with a nice upward appreciation of the stock price over time. Moving a drug program into multiple clinical trials and hundreds of patients is capital intensive – but can also be very capital efficient with strong data in the right market environment.

Those are clearly two “red-line” companies. Many others exist in the current crop of recent IPOs: Epizyme, Aratana, Karyopharm, Ultragenyx, etc…

Another flavor of the “red-line” capital efficient company would be those that get bought at premiums in value before raising additional capital. Seragon and Labrys both raised only ~$30M in equity before being bought for $725M and $200M upfront, respectively. Clearly those are very capital efficient deals – and could be illustrated by nearly vertical lines in Exhibit B.

But lots of “black-line” companies exist. AVEO’s “go big” approach demanded it raise $200M+ from 2005-2011 at flat prices of $9-11/share; unfortunately their late stage asset’s demise has left them in a challenging position (see prior AVEO blog here).

But not all black-line companies fail to work out: Portola raised $200M+ from VCs over a 7-year period at essentially the same price, roughly $13-15/share; after its IPO, it has moved up to $24, so is a positive outcome for returns but can hardly be deemed “capital efficient” for the early investors.

Many black-liners, though, get recapped over time. Dicerna’s Series A and B rounds faced a 25:1 split, and the common sharesholders a 250:1 split, effective with the July 2013 pre-IPO crossover round (here). Similar splits happened with Ambit and PTC Therapeutics’ early rounds. In hindsight, it’s clear that those players weren’t able to be very capital efficient with their early equity dollars. Late stage investors in those deals may make money (and Dicerna certainly seems to be strong trajectory).

The narrative above highlights how the challenge of capital efficiency is fundamentally an early stage investors’ dilemma; there are plenty of late stage investors willing to re-price your inefficiently deployed early stage capital if you don’t manage your business properly and create enough meaningful value. It’s easy with 20:20 hindsight to see which companies were capital efficient with their early equity and which weren’t, but the trick is how to think about this prospectively.

Unfortunately, of the two drivers of capital efficiency – capital intensity and the cost-of-capital – only the former can actually be managed proactively. Capital intensity is a function of the burn rate, and is therefore at least somewhat predictable. When you start a big platform, you should bet on it requiring a good dollop of equity to bring it to fruition. Start a single-asset “built-to-buy” preclinical project and its likely going to need far less funding.

In contrast, the cost-of-capital is almost purely an extrinsic factor – determined by the sentiment of the markets for high-risk equity in general and your kind of story in particular. In a “risk-on”, QE-supported world like the last couple years, the cost-of-capital in biotech has been at historic lows, clearly helping buoy the biotech markets as a whole and specifically the emerging companies (pre-IPO/IPO-stage companies). Strong data from high profile late stage programs has been a big positive for further upward sentiment. In short, the market’s willingness to offer lower cost-of-capital becomes a big driver of what is ultimately deemed an efficient use of equity capital, and vice versa.

But since capital intensity is the only “manageable” or “predictable” factor, optimizing capital efficiency depends greatly on how that is managed. Being thoughtfully efficient in your deployment of equity is the only defense against unpredictable, negative market sentiments, especially since trying to “time the markets” is a recipe for losing money.

With that link to capital intensity in mind, there are at least four ways to improve equity capital efficiency in any environment – and leveraging the personalized medicine theme of “the right patient, the right drug, at the right time” – I’d call it the “right amount of equity, at the right time, at the right price – and spent on the right stuff”.

- Right amount of equity: “How much should we raise?” is one of the most frequent questions I hear these days. My answer is always the “right amount”. Figure out what you need to spend to get to some clear derisking and value infection, with realistic expectations for near-certainty of delays, and raise that amount. It’s the only way you traverse the red-line in the chart above rather than the black-line. Raise too little, and you won’t have hit the inflection, and you’ll be punished for it on valuation. Raise too much and you’ll have a bloated cap table and a post-money valuation too big for your britches. Importantly, offsetting the amount of equity capital through creative deal-making can greatly reduce the amount of equity required (and greatly enhance the capital efficiency): upfronts, R&D payments, milestones, and other payments can great significant leverage for both the early equity dollars, founding shareholders, and management team.

- Right timing of equity. Tranching, in my opinion, is good for everyone when done in a balanced manner. By titrating in the funding over a set of intra-round milestones, it shields the investor from losing more capital in a deal that fails to deliver, and it rewards the team and founders for seeking alternative cheaper forms of funding (less dilution). It’s a high-class problem to have to say “we don’t need that last tranche” of equity because you’ve found something non-dilutive or at the very least less-dilutive, or achieved an early M&A or IPO without additional tranches of funding. It needs to be done in an appropriate manner though and we strive to find the right balance. I’m sure we’ve gotten it wrong on occasion, but in general it’s a critical element of smart, capital efficient early stage funding.

- Right pricing of equity. This is much harder to control, but making sure you’ve done the first two enables better odds of this one working out in your favor. If you’ve raised the right amount in prior rounds, have an attractive cap structure, and don’t need to raise a ton of new dough, you are in a good place to manage your pricing in a new round – especially if you have insiders with deep enough pockets to go longer without a new investor. The latter point is key to having leverage in the “right pricing” of new equity. It’s also important to ensure that you’ve canvased different pockets of the investor community: later stage VCs, cross-over investors, corporate venture groups, even family offices and angel investors.

- Spent on the right stuff. Making sure you pick the right programs to fund with significant capital early in the life of a company is clearly critical, especially for platform companies. A biotech’s fate largely depends on how compelling is the first major program (as discussed in before in blogs like this one); early target selection that plays to the differentiated strengths of the platform becomes a huge driver of future success. Companies that start to pour funding into less attractive but “more advanced” programs under the practical pressure to “be in the clinic” or “validate the platform” often destroy value. I’d rather see a company take much longer to get to the clinic, but be more judicious and thoughtful about which compelling program(s) to fully power up and advance into development – because that’s where the capital intensity ratchets upwards. Playing with lots of projects in drug discovery, killing the less compelling ones quickly and cheaply, is critical to channeling larger amounts of equity capital into the “right stuff” over time. As investors, we do this at both the portfolio level (our cohort of seed-stage and asset-centric companies) and at the company level (where platform companies allow for broader product candidate portfolios).

Optimizing the capital efficiency of a deal – and of an entire early stage portfolio – is clearly more art than science, and it certainly isn’t “small ball” as some would suggest. It requires some dynamism around market sentiments, but fundamentally, a sound early stage investing strategy is one rooted in managing the capital intensity of a deal to fit the business model – which goes a long way to ensuring a capital efficient outcome for the company and its shareholders.