Amidst lofty public markets and robust fund flows, it’s easy to forget the importance of equity capital efficiency in building new biotech companies. But like gravity, it’s a fundamental principle and rests at the heart of generating quality returns in any market. By deploying early, expensive equity dollars carefully and thoughtfully, a startup can preserve its upside in a wide range of market outcomes.

Capitalize a startup too much but fail to achieve escape velocity (or miss the market window), and the inevitable hiccups of drug R&D will severely punish returns. The flip side is also true: starve a company, fail to achieve key milestones, and a challenging fate is sealed. The optimal equity capital efficiency is a goldilocks challenge and has to fit the business opportunity in front of it – one of finely balancing the cost of capital with the burn rate and subsequent value creation within companies (here). The impact of capital efficiency on returns has been discussed many times here in the past (here, here).

A recent Silicon Valley Bank report from Jon Norris and Kristina Peralta caught my attention as it highlights the compelling impact of being smart with your equity dollars if you want to preserve the potential for attractive returns in an M&A setting.

Their report covers the broader funding and exit environment in biotech, and is well worth reviewing. The summary first line captures it all: “The overall boom in healthcare propelled fundraising, investing and exits in 2014 to the highest level in several years, eclipsing our bullish outlook from a year ago.”

But the hidden gem in the data they present was their finding around big exit M&A values, estimated returns, and the impact of equity capital efficiency.

Norris & Peralta looked at 85 M&A exits in BioPharma that were larger than $75M upfront (so called “Big Exits” in their analysis). This includes deals like Alios’ acquisition by J&J, Seragon’s by Genentech, Labrys’ by Teva, CoStim’s by Novartis, and many other exceptional deals. As noted before, the M&A environment in recent years has been very strong (here).

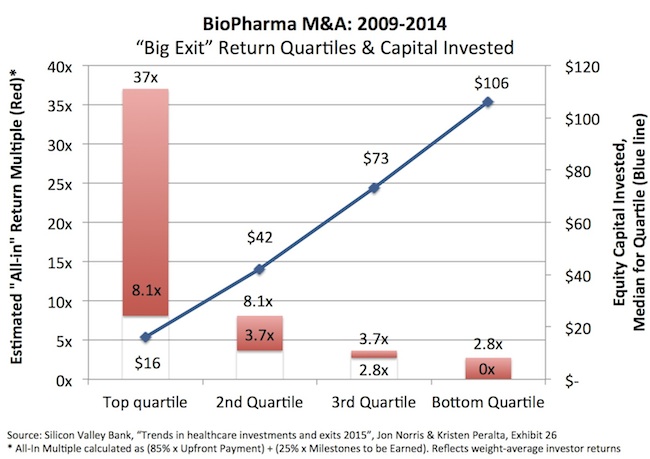

The authors estimated “all-in” returns to investors by taking 85% of the upfront payment and 25% of the future milestones; these are reasonable if not conservative assumptions given the experience with milestone payments recently (here). They created return quartiles in this dataset and looked at the median amount of capital raised in each group.

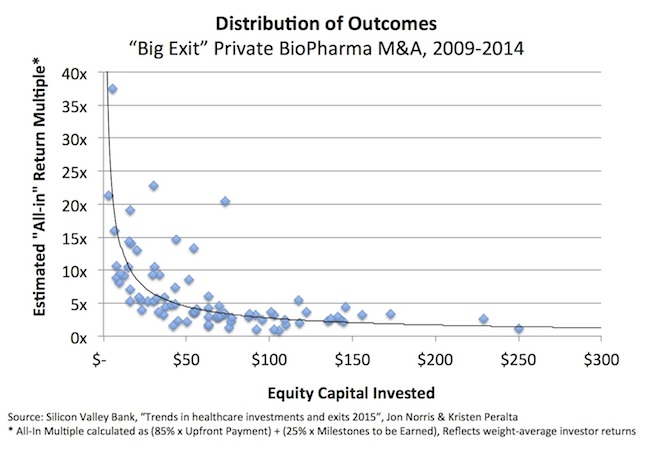

The findings, re-plotted below as both quartile analysis and a distribution, are striking:

Two obvious observations from the data:

- A very clear inverse correlation exists between investor returns and equity capital deployed. Pouring equity dollars into deals isn’t driving up M&A returns; or, said another way, M&A values don’t move up proportionally with invested capital. Returns from acquisition-based exits frequently go down with increasing amounts of funding.

- Top quartile return multiples are very attractive – above 8.1x. The companies in this dataset are obviously “winners” in that they attracted >$75M upfront, so its to be expected that this “success biased” quartile distribution would be skewed upward from broader deal datasets. These returns represent top 3-5% outcomes in the VC business.

A few other statistics called out by the authors are worth highlighting:

- Within the top quartile, 19/22 deals raised less than $50M in equity capital, and zero raised more than $100M.

- Ten deals (in the top quartile) have had M&A return multiples more than 10x of invested capital, and three above 20x.

- In the bottom return quartile, 19/21 deals raised more than $50M, and 12 more than $100M.

- Since 2009, only two M&A deals with more than $70 million in equity invested returned multiples greater than 4.5x.

A couple caveats are worth calling out in the data. The “big exit value” calculations could be much higher if milestones are paid out, and this could skew the analysis; unclear from the data if there’s more “at-risk” in the lower quartiles than the upper quartiles. Further, these are “all-in” returns, as the authors call it – which means they are an estimate of the weighted average investor returns. Because of this, the actual returns to early or later round investors could greatly differ from these depending on the pricing of the rounds. It’s a good approximation, historically, for estimating returns for investors.

These observations are entirely consistent with prior analysis. In fact, the distribution curve looks remarkably similar to an analysis published in Nature Biotechnology in 2007 called “When Less Is More” on the subject of capital efficiency (see Figure 3a here).

In today’s IPO-centric market, where the cost of capital has been dramatically reduced versus the 2003-2012 period, the opportunity to scale companies more aggressively and earlier in their lifecycle has opened up new options for startups. Having a credible alternative to Pharma M&A via the IPO route has certainly enhanced returns for investors and management teams across the board, and creates a path for building then next Genentech, Vertex, Regeneron, and the like.

Companies like Agios have exhibited remarkable equity capital efficiency in how they have taken advantage of the public market opportunity to scale: the Series A, which brought in a tranched $33M raise, was priced around $3/share, and its trading at 35x that value today. A big part of how Agios and other companies have done this is via creative business development; their landmark deal with Celgene allowed them to scale with non-dilutive funding during a critical time for the company, which opened up multiple options (and new disease areas) to the startup.

If well structured, less dilutive funding mechanisms via creative collaborations can catalyze significant value creation and optionality for young companies. As the SVB authors note:

Thus, companies should look to leverage non-dilutive funding when possible. Many companies started since 2009 have diverse asset pipelines, and partnerships with big biopharma can help by providing non-dilutive funding and validation of the technology. In addition, we have seen an upswing ?in patient advocacy groups that are providing non-dilutive grants to help defray clinical costs in specific trials. This also provides clinical development opportunities for companies without adding to equity capital.

Its not uncommon in today’s market to see young startups aggressively capitalizing themselves and scaling quickly – the allure of going public early and at lofty valuations has considerable appeal, and can generate great returns if well timed and the markets remain accommodative. If public market investors want to jump into an early stage story at lofty valuations, a startup definitely needs to take the interest seriously. This can be a route to achieving escape velocity – the speed with which one can overcome the constraints of gravity. Over the last decade, there are a number of companies that have done this successfully (and Denali, announced yesterday, may very well become one); but there’s a far longer list of companies who haven’t been able to turn their capital intensity into gravity-defying velocity.

The rocket fuel approach can work well in buoyant markets, but it’s not without its risks. There’s a tradeoff that needs to be balanced; significantly over-capitalizing a startup too early can elevate the risk of less disciplined resource allocation, but it also greatly reduces the degrees of freedom for what an attractive exit path might be – and can often take viable M&A off the table. Although there are exceptions, Pharma by and large won’t regularly pay billions for preclinical assets. Preserving exit optionality has real strategic value.

This new SVB analysis drills home the principle that disciplined equity capital efficiency – and creative business development – provides the opportunity for generating great returns in both M&A and IPO exit environments.