This blog was written by Michael Gladstone, Principal at Atlas Venture, as part of the “From the Trenches” feature of LifeSciVC.

For a great company, an IPO is a financing event. Not an exit. Not the end.

This is important to remember. It seems we’ve been hearing more about the shakiness of the biotech IPO window. Usually, observers cite one or both of two main factors:

- Recent volatility and perceived losses in the biotech market

- Failures of several IPO’ing biotechs to meet their targeted price range

Re: #1, given my role and my firm’s focus, I’m somewhat less interested in the gyrations of the broad public market. At Atlas Venture, we are long-term fundamentally-driven biotech investors, with a focus in transformative therapeutics companies striving to discover and develop new medicines. This takes years, and if it succeeds, savvy early investors are usually rewarded regardless of the state of the public market. That being said – at the time of this column’s writing, the Nasdaq Biotechnology Index (NBI) is up 9% from the start of the year, and is higher than it has been any time in history before 2015. I don’t know what the future holds, but it does not feel today like the sky is falling for biotech investors.

The perception of point #2 above is more interesting to me. Fierce Biotech published a story with the title “Biotech IPOs are staggering as the bulls begin to fade back.” Citing two recent early-stage companies that have priced IPOs below aggressive pricing ranges, John Carroll writes, “The IPO window may not be closed, but the giddy days of going public with sky-high valuations appear to be behind us–at least for now.”

But are things really so bleak? Carroll uses the examples of Dimension Therapeutics (whose IPO priced at $13/share, below $14-16 target) and MyoKardia (who priced at $10/share, below $15-17 range). But what valuations did these companies go out at?

Dimension’s IPO post-money was $350M. By virtually any metric, this is fantastic for a pre-clinical company, and it is a testament to the quality of Dimension’s team, programs, technology, and Bayer partnership.

Likewise, Phase 1 MyoKardia’s IPO post-money was $275M, demonstrating clear interest from public investors in their novel cardiomyopathy therapies.

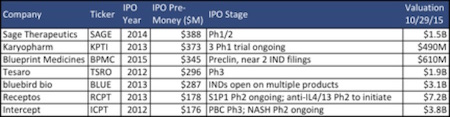

These valuations compare very favorably to many IPOs deemed very successful and which financed similarly high-quality companies to additional clinical data-driven value inflection points.

This has several key implications for me:

- Dimension and MyoKardia actually debuted with valuations the compare favorably even with some of the highest flying IPOs of the last several years, including compared to companies with more advanced programs

- Many of these successful IPOs may actually look “cheap” today, given how much value was created subsequently by each of these companies, driven by effective development of paradigm-changing medicines with the IPO funds

- And, most importantly: the ability of these biotechs to raise large pools of capital at these strong valuations enabled them to continue to build their companies and develop their drugs, providing new options for patients and rewarding public investors and pre-IPO investors alike

The last point is key. Making medicines is hard, and it costs money. For a biotech company and its investors, an IPO is an opportunity to access additional capital with an acceptable cost, which funds the company to continue to develop its drugs.

If the pre-IPO investors are also able to recoup some of their initial risky investment (and ideally make a profit in the process), that’s great both for those investors and the biotech ecosystem that relies upon them to build and fund the next round of new companies. But for most investors (and of course for the biotech company and the patients that may benefit from it), an IPO isn’t the end of anything. It’s just a way to finance the continuation and acceleration of new drug development.

Maybe some companies have been aggressive in their targeted price ranges. Great! This is in the best interest of their investors, founders, and employees, and the higher their valuation, the more capital they can raise to advance their programs. But the perceived “staggering” of these companies here seems to be a product of these aggressive expectations, rather than a genuine misstep or disappointment that bodes poorly for the industry.

Viewed in a vacuum (or even relative to the fantastic biotech IPO performance of the last several years), these are excellent financings that will enable great companies to continue to trek forward. If preclinical or Phase 1 companies can raise $50-70M at valuations of $275-350M, that’s fantastic news for investors, the drug developers at those companies, and the patients who rely upon them. Let’s hope things stay that way.