We all recognize that realizing value from a biotech company has historically been geared to one of two paths, IPO or M&A, and that they’ve both been getting tougher. There’s been a number of articles recently about some of the new corporate structures geared to achieving returns in the absence of an IPO or a trade sale, and so I thought it would be worth highlighting both the context and specifics of these approaches.

Every biotech needs to understand its “liquidity thesis” – essentially, what is the “unit” by which value will be realized for shareholders.

Company-centric models of value realization like IPOs and M&As are clearly the norm, and can still work. Take Plexxikon’s recent acquisition as an example: 10-years and $65M or so in equity later, they were able to sell their company for $805M to Daichi, in large part due to the excitement of the BRAF program. Or the recent success of cancer play AVEO: up over 100% since its IPO in Feb 2010 as its later stage kinase inhibitor looks increasingly promising.

But betting from the outset of a NewCo on either of these paths is very hard to do today: a long road with little to no stock price appreciation for years until a value-realization moment isn’t a great way to encourage capital flows into early stage innovation. Plexxikon and AVEO had little to no stock price increases for the better part of last 10 years, quite testing for the nerves of any early stage investor. Furthermore, although a Big Pharma buyer may want the infrastructure and capabilities of a company, more often than not they just want the programs. Pushing them to buy the company for the programs often undervalues the discovery engine. Or vice versa. This company-centric liquidity thesis is incredibly challenged in today’s capital market and sector ecosystem.

An alternative model is the “Asset-centric” liquidity thesis where unit of monetization and returns is via single programs. Setting up single-asset companies is one way to do this. We and others have explored this extensively and we’ve got a subset of our portfolio pursuing this approach (e.g., Zafgen, Stromedix, Infacare) and a new initiative to set up more of them (e.g., the Atlas Venture Development Concept). But single product plays aren’t the only way to do this.

Platform companies that can repeatedly and sustainably discover and develop proprietary drugs can also be structured around an asset-centric liquidity thesis, whereby individual deals can generate liquid returns for shareholders. Conventional C-corps are punitively tax-inefficient vehicles for this approach: licensing payments would be taxed at the corporate income level and then again at the C-corp shareholder level – such of loss of value due to tax inefficiency is often prohibited in VC partnership agreements. But a more tax efficient structure can be employed by leveraging LLC structures. Traditionally, LLCs have been a challenge for institutional VC firms for a variety of arcane tax and accounting reasons, but there are several ways of working with them that are increasingly common:

- LLC “holding company” model. We’ve embraced this approach with Nimbus Discovery. Its an LLC “parent” company with individual C-corporations (Inc’s) as wholly own subsidiaries. The platform and team are housed in a ‘management’ subsidiary, and as each program is generated it is moved out and housed in its own entity. When these programs mature to partnering stage, our aim is to have Pharma acquire them cleanly for the IP and data package in an earnout approach (e.g., upfront, milestones, downstreams). The value from the sale of the equity flows through the LLC as capital gain back to shareholders. And we’ll keep working on new programs over time.

- Standalone LLC model. As I understand it, Adimab, Ablexis, and Resolve Therapeutics (and one of our AVDC companies, not yet announced) have been structured in this manner. In this model, licensing deals or technology access payments for specific assets can be channeled through to shareholders directly as LLCs are “pass-through” entities. Most start this way at their inception, but Adimab actually converted itself after its Series D from a C-corp into an LLC (not a small feat, nor a small legal bill; Errik Anderson deserves a ton of credit). Typically, institutional VCs will need to set up special entities that sit between a venture fund and the portfolio company to protect some of their LPs from tax issues. But when the favorable economics of the LLC model are shown to LPs, the choice to go with an LLC becomes quite rational.

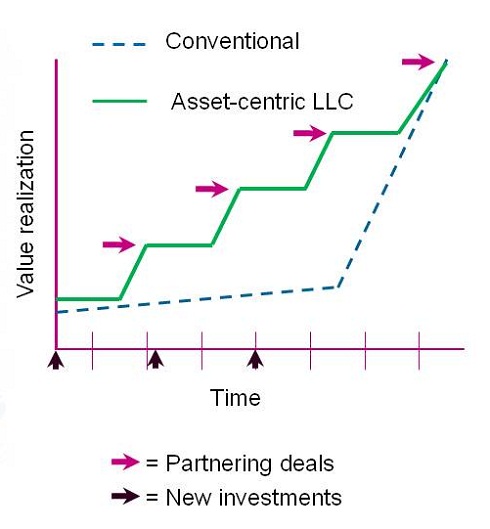

Importantly, both of these LLC structures offer all the normal liquidity options (i.e., M&A or a down-the-road IPO), while opening up new avenues for achieving liquidity. And this new angle on liquidity should help solve one of the biggest challenges in the venture funding of discovery platforms: long, liquid timelines where capital is locked up at flat prices. Asset-centric monetization should smooth out the value creation curve and increase the velocity of capital (and IRR) of investments, as per the idealized chart below.

Like any new or unconventional approach, the LLC concept often elicits an initial negative immune reaction. But I think its here to stay, and should help the sector drive improved returns. I’m also an evangelist for it because the more of us that use it, the more commonplace it will become, and the less friction that will be caused by the novelty of the structure. (Its worth noting, btw, that many angel-backed or bootstrapped biotechs have been LLCs in the past; it’s just never been a structure adopted by the venture community given the historic IPO bias)

Few tips for those entrepreneurs/investors considering LLCs:

- Start with the LLC model at the very beginning. Instead of defaulting to a C-corp as an entrepreneur, go with an LLC. Adimab’s structure switch feat isn’t for the faint of heart.

- Get a good biotech lawyer to structure it. There are many great counsels who will kindly overcharge you, but Mitch Bloom at Goodwin Procter really helped at Nimbus and earned his fees.

- Hire good accounting help to track ‘project’ financing for each program. Solid, well-organized budgets and reporting are key to making the model work.