Pharma corporate venture was back in the biotech news today with the release of Burrill & Company’s June 2012 report. An interesting article by Vinay Singh evaluated the impact of Pharma corporate venture capital (CVC) investing, and the key takeaway is that CVC-backed companies have a higher rate of overall success than those without their involvement.

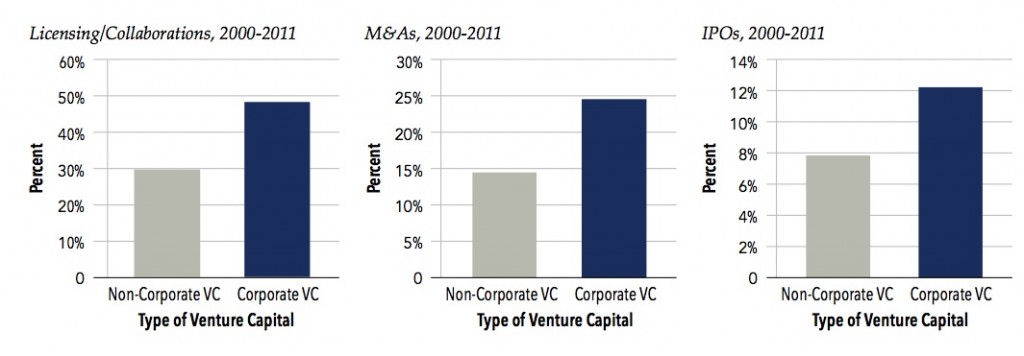

While a similar takeway has been published before by Windhover’s StartUp about a year ago, these data suggests a fairly robust effect from a large dataset. The analysis includes 2907 therapeutics companies that raised venture capital dollars between 2000-2010 across 5100 rounds of financing. Corporate VCs were investors in about 10% of companies, and this pool of 286 companies had what appears to be a markedly higher hit rate: a ~60% higher rate of licensing deals, M&As and IPOs. The figure from the article is pasted below:

As an aside, its interesting to note that the “CVC participation rate” in biotechs of ~10% over the decade reported in this Burrill article supports the perceived uptick in corporate venture activity today when compared to more recent cohorts of data. A recent report published by NVCA/PWC in their MoneyTree earlier this year suggested that 18% of all biotech deals had CVC involvement in 2010-2011. My guess is this rate of 1-out-of-6 biotechs with CVC involvement today probably holds for the aggregate biotech funding rate across all company stages. However, while I don’t have the data breakdown by stage, from what I can tell the rate of involvement in Series A rounds is probably closer to one-third, at least in the Boston biotech cluster. As I’ve written about before, Atlas’ recent portfolio of new Series A-stage startups has a participation rate with pharma corporate VCs of 70% or more.

So these new data from Burrill are entirely all consistent with pharma corporate VC playing an important role in the ecosystem, and that they seem to get involved in good companies that possess better than average probabilities of success.

But the killer question is whether corporate VCs are just good company pickers because they look for things their Pharma R&D organizations may want, or if they actually help shape a better outcome once they get involved either through the value-added “stamp” of Pharma validation or through active deal management contributions. I’ve certainly seen lots of evidence of the latter, so am biased to that answer – but it’s a chicken and egg type of question.

A big caveat to all of these generalizations is worth mentioning: if there are different styles among independent early stage venture capital firms, then its fair to say there are different species amongst corporate venture capital firms. The two ends of the spectrum:

- Standalone CVCs: These firms behave as quasi-independent venture groups, driven foremost by financial metrics but relevant strategically – like SR One, Novartis Ventures, Lilly Ventures, Medimmune. These firms typically function more like traditional VCs: they lead/co-lead rounds, drive a pricing process, and typically take on Board seats. They also tend to maintain high walls of confidentiality from their corporate R&D groups. Lastly, and importantly, they only recuse themselves from Board discussions in a portfolio company if it involves a strategic process with their parent company; otherwise, they are active and often vocal contributors to a BD debate.

- Purely Strategic CVCs. Other firms have a more explicitly strategic mandate, including firms like Amgen, Shire, Abbott, BI, Baxter, etc… These firms tend to join existing syndicates in companies focused on areas of deep franchise interest. They rarely lead the negotiation to price a new round, and most often only take on Observer roles on Boards. During BD discussions, the representatives of these firms typically leave the Boardroom.

The Burrill dataset may be large enough to explore which of these CVC species has contributed to the outperformance suggested by the data. But it would be complicated, as many corporate VCs have morphed their strategies over time. For instance, in the early 2000s, SR One and Novartis didn’t typically lead rounds, they were followers in most syndicates; today, my guess is they lead or co-lead everything they do.

Even if we don’t have performance data broken down distinctly, it is fair to say that the contributions these divergent CVC strategies can bring to an early stage biotech company are very different. Strategic CVCs may plug a company into their R&D organization much more deliberately and bring the capabilities of the parent to bear more explicitly. On the flip side, standalone CVCs bring Pharma insight, smart company-building capital, and a strong governance role – in some ways filling the vacancy left by the shrinkage of the traditional venture firm.

We enjoy working with both, and will continue to. But for biotech’s thinking about their next financing, knowing what you need from your syndicate and how it maps to these differences is certainly important as you choose your next investor.