Five years ago I stepped into my first (and so far only) CEO role. It seems impossible that it was five years ago but I definitely still remember many moments from my rookie year as a CEO – both successes and mistakes.

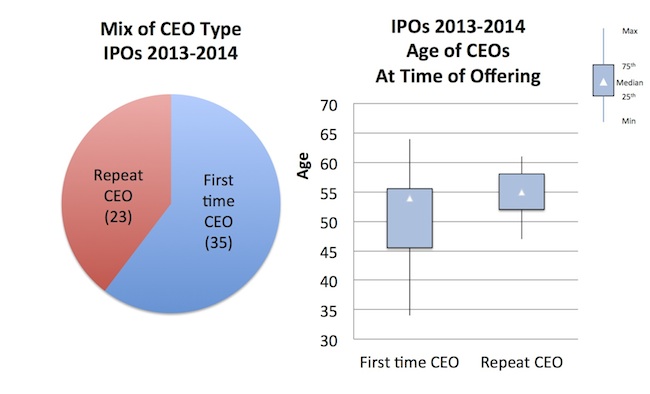

Since the beginning of last year, I count 58 biotech companies that have gone public, and 60% of them have a first-time CEO at the helm. It’s certainly an experienced group in other ways – the average CEO age across all those newly public biotechs is 53 years old and over 70% (42 out of 58) are in their 50s or 60s. Even for the 35 first-time CEOs, the average age is 51 at IPO. Here’s a chart capturing the data:

First-time CEOs were more likely to be founders of the company as well, but this was still a minority:

- 43% of first-time CEOs were founders (15 out of 35) but only 26% of repeat CEOs were founders (6 out of 23)

- Overall, 37 CEOs out of 58 were not founders (64%)

But the experiences of my colleagues and myself tell me that regardless of the road travelled and the number of miles entailed, there are still aspects of that Rookie Year as a CEO that catch you by surprise. Jumping those hurdles can make or break a new CEO’s ability to step up to the plate for a sophomore year.

So in the classic mode of what-do-I-know-now-that-I-wish-I-had-known-then…and with great insights from several friends and colleagues, a few thoughts on the Rookie Year.

Talk to your Board. Frequently. But about the right stuff.

In addition to being a rookie CEO, there’s a very good chance that this is also the first time you’re on a Board of Directors. You may have given presentations to Boards before or sat in on Board meetings, but it is fundamentally different when you’re CEO.

Your Board can help you find your footing – they definitely want you to be successful. The last thing they want to do is have to go find another CEO (their ultimate recourse).

A big part of this is figuring out how to use Board meetings versus what to communicate outside of that setting. A Board agenda that includes every member of the leadership team giving an update is not a good use of time. It can be hard to tell a senior team member that they’re not presenting to the Board when they’re used to doing so; they may interpret it as their work not being high priority.

Yes, the Board wants and needs to know what’s going on, but they do expect you and the team to run the company. Board meetings are to discuss and debate issues. Keeping your Board members apprised of key info along the way and prior to live meetings is critical; NO ONE likes to be surprised at a Board meeting.

Board engagement is at least 20% of where you spend your time as CEO. Think about it – that’s at least a day out of every week. Every Board member I know loves it when the CEO reaches out informally to brainstorm or to find out what’s on their mind or to ask for an important introduction or just to get a drink and catch up. This was the #1 point made by Board members I talked to about rookie CEOs (and, actually, not just rookies).

You cannot and will not make everyone happy.

I remember an afternoon when a senior team member knocked on my door and wanted to talk about a program that had been discussed in a meeting that morning.

An important decision was coming up about whether to continue the program, and this person advocated stopping it because they felt there was a much better program that should be resourced instead.

About an hour later, another person came by to talk about the same program but with the exact opposite view.

Both people were thoughtful and their only agenda was what they thought was best for the company. But at that moment I really understood the phrase “you can’t make everyone happy.”

This is perhaps a particularly stark example; there are many more nuanced instances where you can feel whipsawed by contrasting input from different Board members, or new versus old investors, or new versus old employees as the company grows, and so on. A colleague who serves on a number of biotech Boards said that wanting to please everyone is one of the most common issues he sees with first-time CEOs.

You will never stop thinking about raising money. As soon as you raise money or do a deal, you will realize that you need more money. Soon.

Ironically, you don’t really want your team or the Board to worry about this too much. Certainly the team is a part of the fundraising process – a critical part – but you try to protect their time so that they can actually advance the science and the programs. It’s a tricky balance. But as CEO, you are always raising capital. Always. Especially when you’re not.

You are always on display.

If you’re cranky because you just came in on a redeye and got a flat tire in the rain driving to the office (I remember this day well)…sharing that mood at the coffee machine is a bad idea. There’s a very good possibility that someone will interpret it as (a) you think they’re doing a bad job, (b) something really bad is happening with the company, or (c) both.

We all have both good days and bad, but as CEO, you have to be cognizant that you are always being interpreted. This includes all aspects of how you present yourself, and while there’s not a style formula, you have to be aware that you’re always sending messages – if you swear in a meeting or check your email during a presentation; if you wear a fleece and jeans or a plaid suit; if you’re late; what kind of car you drive; whom you bring to the company holiday party. All of this is scrutinized in a way that it’s not in other roles.

Ultimately, authenticity wins. You can’t be so self-conscious that you’re artificial, and over time, you do better understand how to handle this. But in that first year, it can feel uncomfortable at times.

Yes, it’s a lonely job, but people are incredibly willing to help you.

One time my team and I were having a pretty tough debate about our company’s mission and goals. Everyone cared deeply about the topic, but the discussion was going in circles, and we were all rather frustrated. I had run out of ideas.

What I did know was that I had friends who were also CEOs & Directors. And I called them. I cold-called six different people, described what I was trying to figure out, and asked if they had any ideas or if they’d ever faced this kind of challenge.

Every single person called me back within a day and every single one had at least one very helpful idea. No one had faced exactly the same challenge, but they all had a fresh perspective and offered specific ideas of stuff to try. It broke the logjam in my head (and, by the way, helped me better see the points my team members were trying to make). At the next team offsite, we made a ton of progress. I don’t know if they remember those calls, but I’m still in debt to Vicki Sato, Tom Hughes, Michael Gilman, Mark Leuchtenberger, Jeff Hatfield, and Kees Been. Thanks guys.

Your Board and your team are great resources, but that’s not enough. Cultivating a personal posse of advisors is the third leg of a stool to support you.

Team cohesion is an input, not an output.

I really wish I had understood this in my rookie year. I used to think that talented individuals would become a strong team by working together, that team cohesion was a by-product, an output. I was wrong.

Certainly working together and solving problems creates bonds, but building a strong team is a goal in and of itself and requires explicit time and effort. It’s an input to success. If you work on team-building, the quality of work is better, it’s more efficient, it’s more fun, and it’s what makes you ready to handle unexpected issues and opportunities.

If you’ve ever been part of a truly great team, you know what that feels like. If your current leadership team doesn’t yet feel like that, then it’s time to work on team-building. If someone new joins your team, then it’s time to work on team-building. If your company is growing or changing, then it’s time to work on team-building.

—

This certainly doesn’t cover all of the qualities necessary to be a good or great CEO – it’s a constant learning curve. But the first year may be the steepest.

A closing thought – I also asked some of my investor colleagues and fellow Board members what they look for in a new CEO, since the Board is who hires ‘em. Hiring an experienced CEO certainly seems easier and perhaps entails less risk than someone who’s untried in the role. But since so many biotech CEOs are indeed first-timers, Boards also clearly willing to take a risk on a rookie.

Of course there’s a long list of desired qualities (experience, intelligence, poise, interpersonal skills, etc…) but they also focus a great deal on why.

Why does someone want to be a CEO? What is the person’s primary motivation? Ego? Wealth? Medical innovation? Power? Status? As a stepping stone to something else? To bring important new medicines to patients? Because it’s the next challenge? This motivation will underpin the potential CEO’s leadership style so it is critical to understand for both the Board and the candidate thinking about this role.