This blog was written by Mike Gilman, CEO of Padlock Therapeutics, as part of the “From the Trenches” feature of LifeSciVC.

I stumbled into a bit of a mess a few weeks ago. It was with the best of intentions, of course. Chemical & Engineering News had graciously named Padlock among its “Top 10 Startups To Watch” and was hosting an AMA on Reddit to talk about the feature and answer reader questions. They asked me to drop by and contribute.

In response to a question from a sophomore chemistry major asking if maybe she should switch majors in search of better job prospects, I wrote this:

I would add that, unfortunately, medicinal chemistry is increasingly regarded as a commodity in the life sciences field. And, worse, it’s subject to substantial price competition from CROs in Asia. That — and the ongoing hemorrhaging of jobs from large pharma companies — is making jobs for bench-level chemists more scarce. I worry, though, because it’s the bench-level chemists who grow up and gather the experience to become effective managers of out-sourced chemistry, and I’m concerned that we may be losing that next generation of great drug discovery chemists.

The next day this comment had been picked up by the Chemjobber blog, with the title, “Medchem, commodified” and from there it propagated to The Curious Wavefunction blog under the headline “The Death of Medicinal Chemistry?”

I mean, ouch. I was just trying to help.

But it provides me with an excuse to collect my thoughts on the profound ways in which the drug discovery ecosystem is changing. For the better, in my opinion, though not without innocent casualties.

Moreover, it also gives me a chance to explain today’s Padlock news: After two years of virtual virtuosity, we are now opening our own wet lab – two of them, in fact.

The great disaggregation

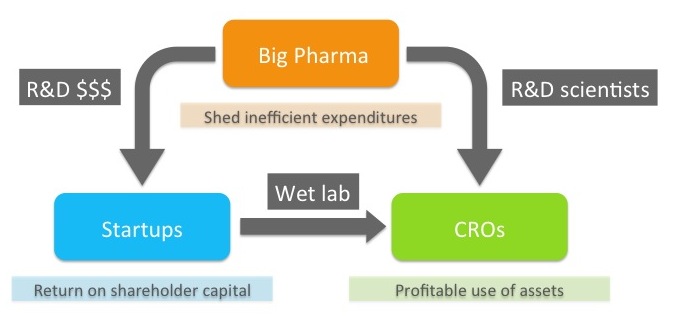

Pharma historians will look back on this decade as an inflection point for the industry when the model for drug discovery changed for good. There’s little question that pharma is under substantial pressure as the world changes rapidly around it. Whether with strategic intent or panicky reaction, pharma companies are responding by shedding inefficient parts of their business.

Among the most inefficient is early-stage discovery. Not, I should add, because pharma scientists are any less intelligent or capable. Rather, it’s because pharma discovery efforts bear enormous and largely legacy infrastructure costs. Equipment, buildings, whole grand research campuses inflate the cost structure of discovery. And human infrastructure – large, layered organizations with byzantine “processes” and seesawing “strategies” – further encumbers the science. The result: unattractive returns on investment. As a consequence, pharma companies are steadily downsizing their internal discovery activities.

Yet the show must go on. People still get sick and die too young – we need new medicines, plenty of them. And while large pharmaceutical companies are perhaps not so terrific at discovering new medicines anymore, they are actually quite good at developing these medicines and delivering them to patients.

But they have to get these drugs somewhere. So they are increasingly outsourcing discovery to the startup ecosystem. They do this directly by forming partnerships with biotechs, indirectly by forming or participating in venture capital funds, and even more indirectly, but no less importantly, when they acquire venture-backed companies, affording investors an exit and enabling them to raise more funds and finance a new generation of startups. One way or another, much of the capital to fund the research done at companies like Padlock, is coming from pharma.

Meanwhile, what’s happening to all those great scientists who are losing their jobs as pharmas downsize their discovery teams? Many of them are being hired by contract research organizations (CROs) – providers of drug-discovery capabilities for hire. Evotec, which is Padlock’s primary CRO, is now the largest employer of medicinal chemists in the UK, having scooped up scores of talented scientists from dead or dwindling UK pharma sites.

Now let’s close the circle. Pharma is outsourcing discovery to startups and sending its scientists to CROs. At the same time, startups are increasingly relying on low-infrastructure virtual discovery models, outsourcing their wet lab work to these same CROs. So, in a way, you have exactly the same folks discovering drugs for exactly the same pharma companies, but in a reconfigured structure in which the scientists now work for CROs and are funded by venture capital managed by an entrepreneurial startup. All while pharma companies simply watch and wait – let others take the risk and then deploy their balance sheets to acquire the winners, liberating the entrepreneurs, investors, and CRO scientists to do it all over again.

Let me tell you why I think this is a very good thing.

Let’s start with the startups. As I argue above, we receive cash directly or indirectly from pharma companies, through the intermediaries of venture capitalists. And we in turn send a big chunk of that cash to CROs like Evotec to do the actual work. At Padlock we forked over nearly half our Series A proceeds to Evotec. So, you might ask, how are we even adding value here? Are we just useless middlemen?

Well, no. Because we have a very specific goal – really our only legal obligation as corporate officers – to generate a return on capital for our shareholders. And while we may occasionally become distracted by other issues, like the science maybe, our investors are always available to remind us of our obligation. (My esteemed editor points out that advancing the science is how we generate shareholder return. Point taken. But I hope he takes my point as well.)

Consequently, we are focused on three key operating principles:

Risk arbitrage. The projects we typically take on in a startup are not secret or mysterious – the science is usually in plain sight for all. Rather they are just a bit too new, too poorly validated, or too risky to appeal to a larger company. Startups thrive on risk – at least they should – and careful assessment and management of risk should be our bread and butter (as I’ve noted previously here and here). So we take on programs too risky for pharma and laser-focus on discharging those risks, so the propeller heads with their financial calculators can calculate nice fat NPVs when the pharma companies come back to have a look.

Disciplined management of capital. We are basically operating on rolls of quarters, constantly having to justify the next tranche of cash from investors. This creates two powerful forms of discipline. One is the intellectual discipline of assessing what we know today and the next new thing we will learn that is actionable (and risk-reducing). The second is the execution discipline to get it done on time and on budget, because we will get precisely the number of quarters it takes to get there and not a single quarter more.

Project management and coordination. This is where the rubber hits the road. No matter how clever we are at arbitraging risk and managing capital, we still to need to get sh*t done. Drug discovery is a complicated business (duh). Assembling a multi-disciplinary drug discovery team, ensuring they stay on track, reviewing and maybe even thinking a bit about the data they generate, is daunting – all the more so if the team is many time zones away. For the last two years, Padlock has consisted of no more than five full-time employees. Yet we’ve been managing a cast of thousands, (well, literally about fifty scientists) dispersed across the globe – Europe, China, India, and all over the US – CROs, academic collaborators, consultants and advisors of every imaginable sort. It’s a very particular skill – and something of an unnatural act for most scientists, who generally prefer to be hands-on. Yet it’s the skill that a virtual company will live or die on.

So, hopefully, I’ve convinced you that we are more than a pack of monkeys seated at typewriters – that there’s a very specific skill set and mentality that is unique to the startup environment that’s precision-tuned to extract the largest amount of actionable, meaningful data from the smallest-possible amount of capital. And that’s a very good thing in the harrowing business of making medicines.

What about the CROs? As I noted earlier, CROs are increasingly staffed with refugees from large pharma companies. These folks are highly experienced and know what it takes to discover and develop drugs. But they are living on another planet now – weird atmosphere, two or three moons in the sky, different gravitational pull. Which is to say that they are in a P&L business operating on fairly tight margins, very different from the environments in which they toiled previously. Managers at a CRO are not concerned about five- and ten-year pipeline evolution. Rather they have quarterly profit targets to hit and therefore need to exercise fiscal discipline in how they deploy their scientific resources.

Let’s recap. We’ve got basically the same money (from pharma) funding the work and the same people (also from pharma) doing the work, but these resources are deployed dramatically differently. The capital is now managed by investors and startups, with a ruthless focus on getting answers, and the work is being done in organizations with a fiscal discipline that would blow the minds of most pharma CFOs. Doesn’t this feel way more efficient than deploying these resources in larger organizations, burdened with infrastructure and, shall we say, a less intimate connection to the bottom line? Perhaps that’s why we’ve seen such impressive strides in just the last few years in how our industry is turning new science into powerful new medicines.

The virtues of virtual

Why be virtual? First of all, because you can. The steady disaggregation of the pharma industry, shuttering of sites, firing of scientists, has fueled the creation and growth of a vast new industry of providers of drug discovery services. Many of these entities are clustered around former pharma sites, like Ann Arbor, Kalamazoo, and St. Louis in the US, where entrepreneurial pharma refugees have built new businesses. And established companies like Evotec have, as I’ve already mentioned, steadily hoovered up liberated scientists from defunct or shrinking pharma sites in Europe. Recently, Evotec took over an entire Sanofi facility in Toulouse, roughly doubling its headcount in one transaction. Every conceivable capability you might need is available from an external provider, and the quality is high.

Second, the success of a startup depends critically (even existentially) on efficient use of capital, just enough to get the job done and no more. That means keeping fixed costs down. At Padlock, our fixed costs (rent, salaries, and other overhead) are roughly 20% of our burn. Everything else is a variable cost, meaning we can dial it up or down on relatively short notice and without having to hire and fire to make those changes. Each month we can precision-tune our spend to the most critical answers we need. And we do.

Third, by outsourcing our wet-lab work to Evotec and other entities, we have also essentially outsourced our organizational complexity. Our organization can stay flat and simple, because Evotec’s isn’t. We don’t need an HR organization – and its endless cycle of performance reviews, promotion controversies, “managing” of poor performers – because our contractors do. Call it HR arbitrage. That’s not just a cost saving; it defines our culture. We are all about getting answers – managing science, not managing people.

But all this capital efficiency is not without offsets. One is the challenge of integrating activities across multiple contractors or collaborators, often on different continents. It’s not uncommon for us to have to ship materials from China to Europe to the US and then back to Europe within a single study. Lots of time and expense) and plenty of opportunity for mishap along the way.

Another is communication. We have many collaborators that we have never met face-to-face because they are thousands of miles away. And because we are basically ugly (North) Americans and expect everyone to speak to us in English – because heaven forbid we should know any of their languages – things get lost in translation all the time. Significant CRO projects are typically managed by weekly or biweekly team teleconferences. It’s not unusual to discuss a proposed experiment only to get on the phone two weeks later to find out it wasn’t done or was done differently than we’d planned – not because of malfeasance but rather because of simple miscommunication or misunderstanding. Issues that would be flagged and resolved in a matter of minutes if the experiments were being conducted down the hall end up consuming weeks of time. And, remember, folks, in our business time is money and money is the oxygen we breathe.

Softer – but no less critical – considerations impact efficiency as well. Scientists at a CRO will never feel the sense of urgency and the sheer existential angst that focuses our minds in a startup. Although you’d think that angst is a bad thing, it’s probably our greatest strategic advantage. We freaking care about what happens in our experiments, because if the project fails we’re going home. The CRO scientists will simply move on to another project. That mismatch in urgency and motivation can be a significant source of frustration in an outsourced program.

I mentioned earlier that many of the scientists at these organizations are outstanding – smart and highly experienced drug hunters. That’s great. But although sometimes you want them for their minds, other times you just want their bodies. You want them to shut up, swallow their objections to your stupid ideas, and just do the damn experiment that you’re paying them to do. Getting this balance right is tricky, because, again, these are talented folks. You want them thinking and caring about your program. But ultimately the responsibility and accountability is with you and not them. Keeping the relationship collegial but still insisting that things get done your way is surprisingly challenging.

Why we’re devirtualizing

On balance, we’ve been very happy with the all-virtual model we’ve pursued at Padlock for the last two years (2014 in “seed mode,” 2015 flat-out). We’ve made terrific progress. We completed two high-throughput screens, have moved forward with more than a half-dozen chemical series, the most advanced of which should deliver a develop candidate around the return of daylight saving time (which is a super-stupid idea, by the way, topic for another blog post). We’ve got some monoclonal antibodies as well. All of this on about $12M in capital spent. No way we’d still have half our Series A in the bank if we’d built out a lab and hired a team of full-time scientists.

Yet that’s precisely what we’re doing this week. We’re actually opening two labs – one in San Diego, helmed by Kerri Mowen, one of our scientific founders who is moving from Scripps to Padlock, and one in Cambridge, where we’ll be bunking for a year with our friends at Unum Therapeutics. By the middle of January, we will have doubled our headcount.

So why?

As I noted at the very beginning of this screed (very long ago, I know), medicinal chemistry has become nearly a commodity, so we are not hiring bench chemists. We have, however, hired a second seasoned drug-hunter to help with the management of all of our outsourced chemistry. Drug discovery chemistry is actually a pretty decent business model for CROs, which, unlike discovery startups like Padlock, are a real business with shareholders who expect profits. Generating those profits quarter after quarter requires fiscal discipline and a degree of predictability – if you employ ten chemists for six months, you know roughly how many compounds they’re going to get. How far these compounds will advance any single drug discovery program is harder to predict. But as a portfolio, medicinal chemistry programs have a relatively predictable cadence that is a better match to the exigencies of running a profitable business.

Biology, on the other hand, especially true discovery, is not a profitable business model – I think we’ve got abundant evidence of that. There’s not much of a script for discovery – it happens on its own inscrutable timeline. When it does happen, however, it’s a thing of beauty and can create tremendous value. But it’s boom or bust. It requires different types of investors, management, employees, and a completely different culture than a conventional P&L business. And now is the time for Padlock to go to a hybrid model, in which we continue to outsource chemistry but internalize and own our biology. We’ve found ourselves in the midst of some fascinating new science – we’ve got a tiger by the tail, I think – and it’s clear we need our own dedicated scientists, bleeding Padlock colors, crying Padlock tears, experiencing all that beautiful existential angst.

And I have to tell you: I am psyched.