This blog was written by Bill Marshall, CEO of MiRagen Therapeutics in Boulder, CO, as part of the “From The Trenches” feature of LifeSciVC.

Dictionary.com defines “outlier” as: (1) something that lies outside the main body or group that it is a part of, (2) someone who stands apart from others of his or her group, as by differing behavior, beliefs, or religious practices (Synonyms: nonconformist, maverick, original), (3) Statistics: (a) an observation that is well outside of the expected range of values in a study or experiment, (b) a person whose abilities, achievements, etc., lie outside the range of statistical probability.

Having spent a couple of decades operating within the life science industry in Colorado, the term strikes me as quite descriptive of the experience in lesser known biotechnology clusters.

My scientific experiences really drove home a deep desire to be open minded and avoid being dogmatic. Old friends characterize it as simply reinforcing a contrarian viewpoint. Fittingly, I thought I’d offer a dialog on the appropriate balance of concentration versus separation as it applies to innovation in the life science startup ecosystem. As you might suspect, I’m an advocate for providing a more balanced distribution of financing to biotech clusters across the country to maximally engage talent and provide additional opportunities for innovation.

The most recent JLL life science trends report ranks the Denver area at number 11, a 2014 Fierce Biotech article listed the Denver metro region at number 12. So the region is just outside of the top 10. However, the disproportionate amount of capital deployed between various regions creates a couple of mega-clusters (Boston and San Francisco) and essentially everyone else. The most recent Money Tree™ Report shows that in Q3 2015, of the $2.9B invested in biotech and medical device, approximately 62% was invested in Boston and San Francisco. Thus there is a significant constriction in the amount of venture funding available to the outliers. While capital constraints in the outlying clusters has always been the case, there has been a significant magnification since the financial meltdown of 2008.

The restriction in availability of capital actually provides a heightened bar for the quality of the science and the team in outlier startups that are successfully funded. The concept is akin to the notion that the significant pullback in the amount of capital available to startup activity as a result of the 2008 meltdown led to an enhancement in the quality of funded organizations.

First off, let me state clearly that I think very highly of the companies and individuals that are operating in the mega-clusters. The many collaborations with them and opportunity to interact on a regular basis have been vital in helping to define a path for miRagen. I also fully understand many of the reasons that investors have focused on company creation near their own backyards. I appreciate many of the theoretical advantages of clustering companies of similar endeavors as they can leverage common resources and promote common interests. However, it seems to me that there is an optimal size of clustering that leverages many of the benefits while minimizing the detriments of overcrowding.

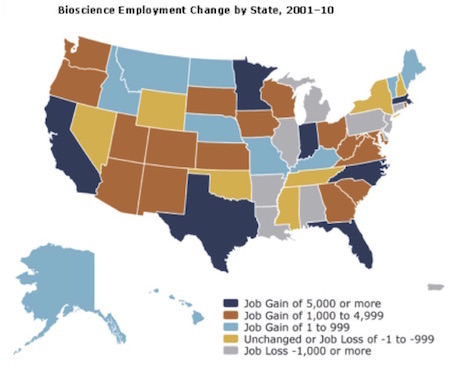

A biotech cluster requires several important attributes; major academic biomedical centers, public and private life science companies, access to capital through government or venture, access to appropriate service providers, seasoned entrepreneurs and a skilled workforce. There are several areas that fit this bill and have entrepreneurial academic investigators generating intellectual property that can serve as the basis for a startup enterprise.

So what makes me think that providing additional funding opportunities to the smaller clusters is a good idea? The notion of outliers being drivers of extreme innovation and progress. To succeed in outlier environments requires a combination of out of the box thinking, technical expertise and past experience. It is also absolutely true that there is amazingly talented and self-motivated individuals that reside in the outlier clusters. Another indicator that dispersion can lead to enhanced innovation comes from Christensen’s seminal book on encouraging innovation in large companies. The classic example being IBM’s movement to create small focused business units in distinct geographies helped the company evolve and thrive.

Biotech clusters are an example of the macroeconomic concept of agglomeration. By co-locating in the same area one is able to leverage supply channels, a supply of trained workers and infrastructure. However, there is an optimal level of agglomeration and when areas become too concentrated they suffer from diseconomies of scale. When density becomes too high, the effects on costs and competition for labor actually have a negative impact on the agglomeration economy.

I also worry that overconcentration of biotech may lead to a form of groupthink that begins to force all investment models in the same direction. The tendency to follow the pack is accentuated in more concentrated environments and may lead to decisions that sacrifice out of the box thinking that has delivered amazing results for our industry.

My biggest concern is that truly innovative technologies and concepts in outlier clusters may not receive sufficient funding to be able to prove themselves. Thus they never deliver on their full potential to lead to a beneficial impact on human health. I’ve seen first-hand examples of innovative companies with compelling intellectual property positions struggle to obtain financing. At the same time, there are examples of what I consider dubious technology concepts that garner large amounts of funding, principally based on their location or founders. While I understand that track records are important, as the FTC disclaimer goes, “past performance is no guarantee of future results.”

The selective pressures in smaller clusters have led to success in discovery and innovation in biotechnology. As I mentioned, the Denver-Boulder area ranks just out of the top 10 biotech clusters, but has a pretty amazing legacy of entrepreneurial researchers and successful startups that have had a significant impact on the industry. Since 2007, the acquisition of Colorado bioscience companies has generated about $11B.

Tremendous innovation and value creation has occurred at many outlier clusters. For instance, Pharmasset was founded in Atlanta based on an Emory University discovery, and was acquired by Gilead for $11B for the life changing HCV drug Sovaldi®. Immunotherapy power houses Kite (Santa Monica) and Juno (Seattle) have created individual market caps of over $2B based on breakthrough drug discovery concepts.

The Boulder-Denver area, like some other outlier clusters, offers an amazing quality of life, a highly educated populace and a level of entrepreneurial spirit that provides an opportunity for innovation in biotechnology. So while our industry will likely always be anchored in Boston and San Francisco, my hope is that the history of biotech innovation in our outlier cluster will continue long into the future. Next time, instead of “flying over”, please stop in and explore the opportunities available in the Centennial State.