Two key geographic clusters dominate the biotech landscape today. These two areas, Boston and San Francisco, combine a unique blend of biomedical science, venture capital, entrepreneurial talent, risk-taking culture, and geographic density. Other regions have some or all of these elements, but not in the same magnitude or momentum that Boston and San Francisco have today – and the gap is just getting bigger.

Last year, GEN ranked Boston #1 and San Francisco #2 in their biotech clusters report (here). Others have covered these clusters and the rivalry between them (here), as the Economist did with “Clusterluck” earlier in 2016. But rather than draw distinctions between them, I’d like to focus on these key clusters relative to the rest of the biopharma ecosystem.

Context

Relative to the US biotech scene, Europe is often viewed as a laggard in the biopharma space from an entrepreneurial perspective. Of course, there are notable exceptions – like Actelion’s incredible success – but, by and large, there’s limited funding, limited R&D-veteran entrepreneurship and risk-taking, and limited prospects for scaling companies. While there is great science across many world-class research institutions in Europe, the commercialization of their science into local startups and emerging biopharma companies remains a challenge.

Two relevant analyses were captured in the data-rich report from HBM Partners on the M&A environment which highlight the essence of this challenge from a venture perspective: US-based biotechs drove faster exits (here) with higher investment return multiples (here) than their EU counterparts.

These data are striking. But how much of this outperformance was driven by the two key clusters in Massachusetts and San Francisco? (I’ll refer to them as the “key clusters” from now on). In an attempt to answer this, I’ve worked with Pitchbook to assemble some data on these two key clusters relative to the rest of the US, as well as Europe.

The quick conclusion is that the rest of the US should likely use the Euro as its biotech currency; outside the key clusters, the rest of the US biotech sector performs and looks a lot like the European ecosystem.

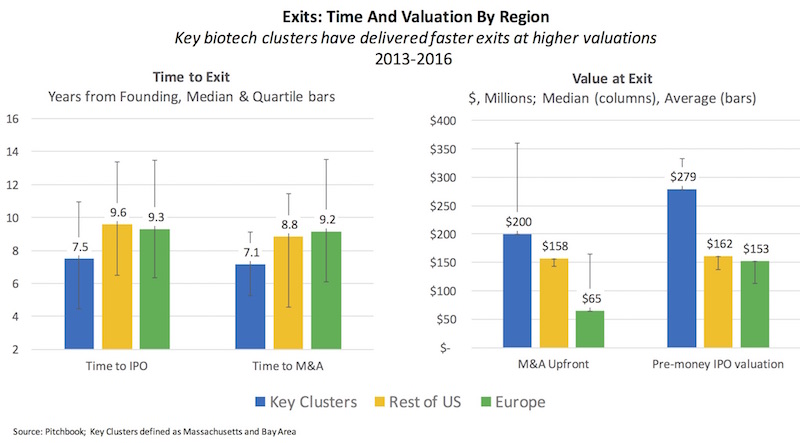

As shown in the charts below, examining either M&A or IPO events between 2013-2016, biopharma startups from the key clusters were roughly two years faster at the median to get to that exit outcome (left chart): 7-7.5 years to M&A or IPO versus 9-9.5 years. The quartile ranges are shown as well. Similar timeline differentials are evident in prior time periods over the past decade as well.

In terms of value, biopharma startups in the key clusters have outperformed both on the median upfront M&A and the median IPO pre-money valuations during 2013-2016 (right chart). The average dramatically skews the distribution upwards in the key clusters (due to big outliers). Again, this differential in value also exists during other time windows of the past decade.

Holding periods and valuations at exit are reasonable but only directional proxies for investor returns. The actual returns depend on pricing of each of the venture rounds, as well as timing of stock sales, etc. But it’s reasonable to assume based on these data that biotech returns in the two key clusters have outperformed other regions.

Why is differential in performance happening?

Biotech historians in the future might call it the “Great Consolidation of Talent and Capital.” While Silicon Valley quickly emerged in Tech a few decades ago as the nexus of all things IT and venture capital, in biotech it’s been far more geographically egalitarian in the past. San Francisco and Boston were clearly important leaders in the early decades of the field, but so were other biotech clusters: Seattle, San Diego, Raleigh, Philly/NJ, Colorado, etc… Most of these also had legacy Pharma or big Biotech footprints that were important for cultivation of talent. And great firms grew out of places well beyond Boston and San Francisco: early winners like Immunex, IDEC, Centacor, Medimmune, and Celltech, just to name a few – and firms like Celgene (San Deigo, NJ) and Amgen (Thousand Oaks) – all born in other geographies.

In recent years, this has changed – Boston and San Francisco are now the preeminent biotech clusters. And their gravity in the ecosystem is only getting stronger.

Beyond having great science and the right “pixie dust” in the local environment, two fundamentally important ingredients to the success of any cluster are capital and talent – and both are aggregating into the two key clusters.

Capital

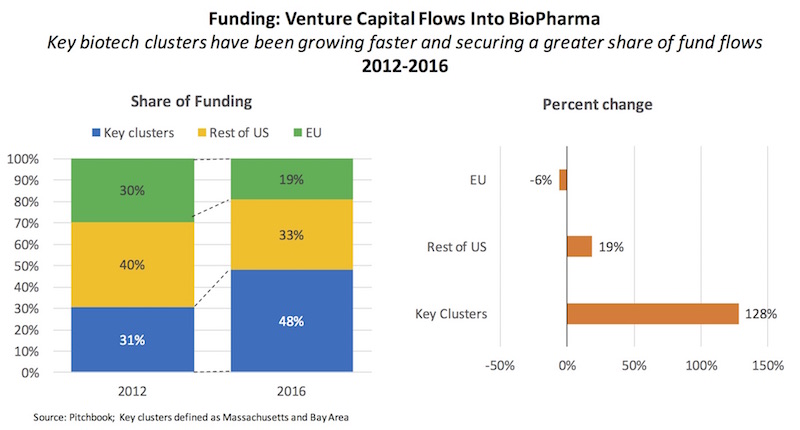

Over the past decade, startups in the key clusters have been consuming ever-greater portions of the global biotech venture capital pie.

As shown in the chart below, since 2012, these two key clusters have increased their share by more than 50%, now securing nearly half of the global venture capital funding budget for biotech. In the US alone, depending on the data source, the two clusters are now receiving 60-70% of the country’s venture pie. Both the rest of the US and the EU have shrunk on a relative basis as a response. The percent change in absolute dollars reflects this – nearly 130% increase in five years into the two key clusters, with the other regions relatively flat or down. Looking back to 2007, most of the change has occurred in the past five years – the distribution of capital across geographies were nearly the same between 2007-2012.

On top of the flow of venture capital, other funding sources are also consolidating into these geographies. Take NIH funding, for instance: California and Massachusetts rank first and second in terms of total NIH funding to its institutions. And Massachusetts ranks a far-and-away first with regards to NIH funding per capita, nearly 3x higher than most other strong states (like CA, NY, PA, NJ, etc). Five of the top six NIH-funded independent research hospitals are in the Boston area (here). Fund flows like these further contribute to the consolidation of biomedical activity into the key clusters.

However, it’s important to call attention to the disconnect between where scientific discoveries are made and where startups are formed. Many of the new companies that get created or launched in the two key clusters do not have scientific roots in those regions. As an example from our own portfolio here at Atlas Venture, despite nearly all of our startups being located/formed in Cambridge MA, the founding science is sourced from all over the globe: Unum came from Singapore, AvroBio from Toronto, Padlock from Florida, Quartet from EPFL in Switzerland, Delinia from San Francisco, etc… About a third of our new startups have roots or connections into Boston’s research institutions, a third with institutions across the rest of the country, and a third outside of the US. So the concentration of capital doesn’t mean scientific sources have shrunk; in fact, it’s increasingly clear to us that science competes on a global stage and we need to access the best substrate wherever it may be – but put the startup where it can take advantage of the benefits of a key biotech cluster.

Talent

It’s much harder to quantify the talent metrics, but one only has to see all the cranes in Cambridge MA to know that big things are happening here. Nearly every major biopharma company has a research footprint in the region. Same goes for the Bay Area, though much more spread out around the region.

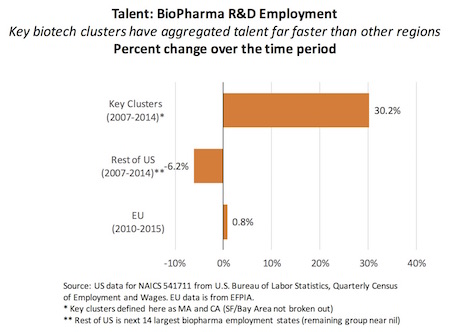

To get a sense for the consolidation of talent, here’s a chart that attempts to capture the change in biopharma R&D employment in the three geographic groupings. The key clusters have seen R&D employment grow by 30% in past decade, versus shrinking in the other major biopharma states (like PA/NJ). Europe, according to their pharma trade group, is flat – though I suspect the metric is actually down in Pharma R&D organizations and up in the CRO R&D world. As a macro point, these data reflect the intuitive sense we have of recruiting talent from other regions into Boston: with regards to R&D teams, prior Pharma hubs are shrinking rapidly while Boston is growing. We’ve even recruited a few sun-loving San Diego biopharma vets to move to the Boston market recently.

As this implies, for startup biotechs, larger biopharma companies are the lifeblood of the talent flows (prior blog on topic is here). Most of our early stage startups are led by teams with experiences inside of larger R&D organizations. The serial cycle of biotech entrepreneurship – starting companies, recruiting talent, discovering new medicines, and getting acquired (or going public) – is accelerated in high density clusters. The entrepreneurial diaspora enabled by biotech M&A is just much larger and more vibrant in these clusters (here). As shown by the data above, faster timelines, more acquisitions, and more R&D talent flows just add more and more water to the millrace, powering the wheel of the biotech mill churning out startups in these key clusters.

As these data suggest, the great consolidation of talent and capital into the two key clusters has clearly been happening in the past decade – and shows no signs of abating any time soon. While the prior return metrics of time and value are clearly lagging indicators of an ecosystem, as they reflect the value creation pace and trajectory in the past few years, metrics around talent and capital flows into startups will most definitely shape the future of these ecosystems.

So what are the implications of this consolidation for different stakeholders in the ecosystem? Here are a few thoughts.

If you are a sector or civic leader in one of the key clusters, some simple advice: don’t get complacent. Make sure the local infrastructure doesn’t fail you at the most critical moment. Congestion, commutes, and chaos can only lead to an exodus over time of those interested in a better quality of life. Further, building capacity to grow will be important; scarce lab space has already driven rents in Cambridge to outlandish levels. We’re seeing startups begin to move back out to the Rt 128 corridor. While still part of the greater Boston ecosystem, those locations are less hyper-connected to the benefits of the density and proximity of the Kendall biotech scene. Lastly, make sure you keep importing ideas and talent into the cluster from around the world or you risk becoming insular; ideas are global, talent is mobile – so keep focusing on bringing them into the region.

If you aren’t in a cluster today, different stakeholders might think about this challenge differently. A few themes:

- Can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. One school of thought would suggest that rather than fighting the consolidation, work to benefit from it. If you are an academic investigator interested in founding a new company, and you want to maximize its chances of success, you might consider putting the startup in a key cluster and create virtual links back to your lab elsewhere in the US or Europe (we’ve done this successfully many times). You’ll need connections into those clusters, but some creative use of email and social media can usually get you that. If you are a tech transfer executive, you might also work to build connectivity with venture creation firms in the key clusters.

- Give them an offer they can’t refuse. The alternative for economic development minded folks in other regions is to enable your local startups with “extra” advantages. Provide R&D credits or funding, like Texas did with CPRIT grants – these significant funding infusions lower the cost-of-capital for young startups and let them progress with less equity investment (since its less available outside of clusters). Unclear whether these are sustainable in the long run, but they could help prime the pump. It’s also important to cultivate more anchor tenants to remain or build in the region; easier said than done, but the revolving door of talent from larger biopharma into smaller companies is a crucial component to a successful cluster. Along those lines, facilitating the return of your regions biopharma diaspora could help; many exec’s in the key clusters hail from other parts of the country or world, and some wouldn’t mind returning “home” like former California investor JD Vance recently did with Ohio. I’m sure tax deductions to successful returnees would spur lots of interest. At the end of the day, in the face of this ongoing consolidation, regions need to figure out how to give their startups a leg up to compete without a major disadvantage.

- Be the big fish in the small pond. This is a riff off the age-old contrarian investor thesis. Much like biotech has been a recent contrarian bet in venture capital amongst many LP’s, creating or investing in startups outside the key clusters could offer some advantages – fewer competitors for the regions talent and capital, even if scarce, means that you could attract more of them. And there’s less threat of losing talent if there’s few other places for them to go. Further, operating costs are lower – both people (salaries) and fixed costs (rents, etc) are often far less expensive outside the clusters. Most of these other regions remain under-appreciated, and a local champion might get a reasonable cut of the “best” ideas in the smaller pond. But you’ll need to figure out how to evolve these businesses into global competitors over time – and one idea is to have a satellite office inside one of the major clusters to access the talent and capital advantages of those markets (which we’ve done with numerous startups in the recent past, like here).

The current trends around capital and talent flows strongly suggest that Boston and the Bay Area will be the preeminent biotech clusters for the foreseeable future – and the global biotech startup scene needs to figure out how to adapt to that reality.