This blog was written by Jeb Keiper, CFO & CBO of Nimbus Therapeutics LLC, as part of the From The Trenches feature of LifeSciVC.

Elon Musk has a flare for the dramatic, shocking Wall Street (and others) the first week of August with his tweet announcing his intentions to take $TSLA private:

The financial and auto industry spent a lot of energy working out the “hows” and “whys” of going private, and many comparisons were made to the large leveraged buyouts (LBOs) of the “Barbarians at the Gate” past. In biotech, “going public” is the thing to do: 2018 has been a banner year for IPOs. Rubius Therapeutics ($RUBY) raised an eye-popping $241 million last month, and it’s just one of more than 30 biotechs to go public since January. The strength of these IPO cash hauls raises the question: With such a go-go market of capital, why on earth would a company want to go, or stay, private? It turns out that staying private is not just for companies that “need more time to mature,” but can in and of itself be a successful path for high performance biotechs – if they address capital needs, provide investors exits along the way, and support a path to significant value creation in the wake of demonstrable scientific and clinical achievements.

While certain investors, the media, and others celebrate an IPO as an “exit event”, at the heart of the matter the corporate IPO is a financing event. The logic for discovery and development stage biotech companies going public is that they’ll get access to “pools of capital they could not otherwise get in the private market”, as eloquently summarized here, here. There are, of course, significant costs and trade-offs when a company goes public, and much has been written about the regulations, reporting, and distraction burden on senior executive time, not to mention dealing with the vagaries of public investors as Mr. Musk was eager to avoid by returning to the “simpler life” of being a privately held concern. A previous From The Trenches blog by @samtruex outlined alternatives to IPO, including reverse merger approaches to address some of the benefits of the public markets without the “IPO process” itself.

Whither public or private? Most answer based on stage of development: It’s time to go public when your company is advancing into clinical development. It’s more instructive, however, to think about it in terms of your company’s ownership: who your investors are and the nature of your relationship with them. When you are an early stage, private biotech, you may have three investors, each with a representative on your board of directors, all of whom you, as an executive, will know well. These investors bring capital, yes, but far more than that, they bring their company-shaping expertise, experience, connections, and partnerships to help incubate your young company. As a biotech matures, by the time it is considering the IPO route it may have ~10+ investors on the cap table (for example through a “crossover” round), and while some of those investors are bringing more than capital, some of them are much more passive, financial cheerleaders, without direct board seats. Just after an IPO, you’ll likely have hundreds of shareholders, and likely only a dozen with meaningful positions in your company (mostly those in the crossover round). Now your relationship has simplified to just company and financial investor, governed by the rules of being a public trust. But you’ve lost the meaningful and intimate relationships with a close group of investors who are truly vested in your company’s success. With this lens, one can see the logic of staying private.

In general, there are three common reasons cited for why successful, growing companies “cannot” stay private:

- Increasing capital needs are only satisfied through the public market

- Public markets offer the opportunity to provide liquidity to shareholders

- There is an inability to realize mega-size returns for success as a private company

While valid points to consider in the process of deciding whether or not to go public, these three challenges are not insurmountable, and have been addressed successfully by private companies, such as Nimbus, where we have remained private for over nine years. To really dig in, it’s worth addressing each challenge individually.

- Satisfying Capital Needs

As a biotech executive, you have only two things you can “sell,” put simply, to raise capital: equity or product (and either directly or by assosciation, platform) rights. In practice these are often referred to as “financing” and “getting non-dilutive capital”– aka pharma BD partnering. The two paths are often in strategic opposition: an IPO is a form of selling equity; avoiding BD deals that give away the farm and retaining key rights to products in the pipeline is essential to get investor interest in the public markets. For early stage investors though, selling equity to new investors is dilutive to their ownership position, and they push management teams to bring in capital that doesn’t dilute the cap table through BD deals. There is certainly an art to balancing those two funding strategies, which I’ve covered before here.

“At some point, though, you will need someone who can write you a $100m check for a late-stage clinical trial,” says a notable public market biotech investor. He’s right that R&D is an expensive endeavor with year-on-year spends that appear to grow geometrically. Here, corporate strategy plays a big role in thinking about where to get capital. For a new company in the cellular therapy space, where establishing manufacturing is a critical early move, spend rates could hit $100m/year before the end of year three. In cases like these, seeking large amounts of capital for major asset construction and deployment requires well-functioning public markets, and IPO is the natural path for these companies. Both the use of proceeds and velocity of spend drive a strategy to move to the public market quickly.

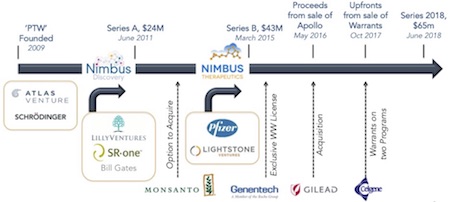

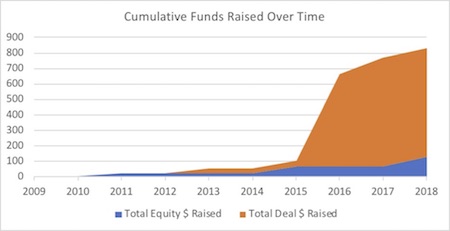

A company focused on small molecules, however, has a different strategic context. The small molecule world has predictable costs, timings and scale, and can be pursued by leveraging CRO collaborators, all of which lends itself to creating a pipeline of drugs that can be either financed or partnered to provide the capital to progress. Forma Therapeutics, a small molecule company, started over 10 years ago with a $4m Series A and they have done multiple successful partnerships and financing that have allowed them to stay private all these years. Nimbus has followed a similar strategy of combining deal-making with financing to grow and develop the company, as illustrated below:

These events led to significant capital accumulation over time through both equity and deals in ranges of upper decile early public biotechs, as illustrated here:

- Providing Liquidity to Shareholders

Much has been written about the tradeoffs on “IPO versus M&A” exits (e.g., here, here), and there are clear lessons to be taken about returning capital to investors. As Nimbus demonstrated two years ago in the sale of one of its subsidiaries for $1.2B ($600m of which came in the first year) to Gilead Sciences, a private company can create an “M&A return” while also continuing operations. That’s much more difficult, if not practically impossible, for a public company (as elucidated in my blog at the time). Capital returns to Nimbus shareholders from “excess proceeds” from BD deals first began in 2016 with that sale, and since then about 80% of deal capital has been returned to shareholders, providing healthy returns while also still fueling the current pipeline of R&D programs for future value creation:

- Realizing Mega Returns

On this point, the staying private argument might be more heavily debated. Investment bankers have clear data showing that public market companies get a much greater valuation lift from positive R&D news. Take the case of Intercept ($ICPT), whose lead drug, obeticholic acid, scored an amazing result in a NASH Ph2 study (“FLINT”) in 2014. The share price soared overnight, taking the $700m market cap company to an implied $7b valuation. Locking in a momentary change of value is difficult, though, as today Intercept is worth about half that valuation. Still, for companies like Receptos (acquired by Celgene for $7.2b in 2015) and Kite (acquired by Gilead for $11.9b in 2017) the public markets absolutely enabled much of the M&A negotiation strategy; it is unclear whether, say, Receptos, had it stayed private, would have been happy to take half the amount and still earn a great return.

However, as in the tale of Intercept above, often times the run-up of public company biotech valuation anticipates some sort of M&A deal, and when the deal doesn’t materialize and the long, expensive road of first commercial launch is followed, share price typically depresses. Regular SEC reports will show that at such times, behind-the-scenes investors betting on M&A switch out to new investors betting on commercial promises.

On the other hand, staying private can realize exceptional value too. Had Nimbus gone IPO six months before the Gilead deal, in those heady days of 2015, perhaps our market cap could have been $400m (taking a generous 90th %ile IPO at the time) at the point where Gilead wanted to buy. An acquisition at that point would be for the whole company, and given the fact that our market cap was a known public quantity, the chances are, our board would have had to seriously consider an offer lower than $1.2b for the whole company. Staying private allowed a much more focused discussion on future potential and reasons to sell / pass, and likely resulted in (much) better returns.

For now, it looks like Tesla will remain a public company and the thought of going private faded in but a few short weeks. In Mr. Musk’s case, there were numerous factors derailing the billionaire, including the fact that the investors willing to take private shares included competitors and a concern by the bond holders in a “private Tesla’s” ability to service that debt (summarized here).

So, will Nimbus ever go public? Maybe. Rest assured, if we ever do, we’ll have carefully thought through the options, trade-offs, and limitations of that strategy, and proved to ourselves and our investors that the NASDAQ Board selfie is worth the trouble.

Big thanks to the many mentors, friends, and members of the Nimbus family who have contributed all of the wisdom behind this blog.