The dreaded “lockup expiry” is something all newly-minted public biotechs begin to worry about shortly after their offerings. The fear seems reasonable: venture investors and other large shareholders, now free to trade, dump large amounts of stock into the market quickly, creating significant downward pressure on stock prices.

Should they be worried about a flood of stock impairing their stock prices? The data suggests, in general, this isn’t a real concern: its more urban legend than reality.

Here’s some background: all major private shareholders, including VCs, typically sign what’s called a lockup agreement during an IPO process. This forbids these shareholders from selling their stock during the first 90- or 180-days after an offering. Once past that date (the “lockup expiry date), these shareholders are generally free to trade their stock – unless they remain insiders. Insiders would include any shareholder privy to material, non-public information, like Board members, management teams, and integral SAB members, as examples. Insiders can only trade during “open” trading windows when all relevant information has been made public, usually following quarterly updates or other major corporate news. Many insiders use 10b5 plans to set up a trading plan for selling a predetermined amount of stock at predetermined price over a longer term period. Atlas Venture, like many other firms, often uses these plans as part of our long term portfolio planning.

Since a lockup expiry releases a number of shareholders to trade, volume usually increases on that day and thereafter, increasing the liquidity or float of a given stock. This is reflected in the average daily trading volume statistics. Most IPOs only involve issuing 20-30% of the shares, and a majority of IPO shares go to long-term public holders rather than investors that will trade in and out. Because of this, most biotechs are very thinly-traded immediately following their IPOs. Before the lock-up, liquidity is a real concern for most companies, as very small changes in daily volume can alter the stock price. This is in part why newly-minted IPOs have such high volatility. Getting past the lockup expiry increases the daily trading volume – though most stocks still remain rather thinly-traded for several years following their IPOs.

In theory, since volume often spikes around a lockup expiry date, it could put price pressure on the stock. Based on a recent analysis from Wedbush, on average, trading volume often doubles around a lockup expiry date.

But what actually happens to stock prices?

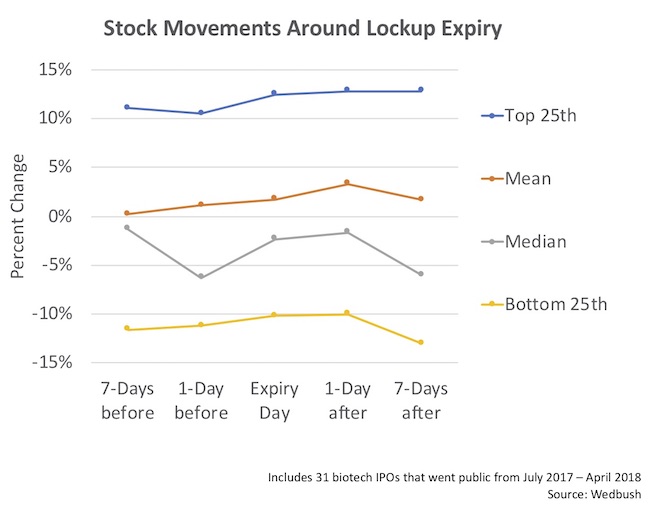

Thanks to input from the team at Wedbush and Cowen, two prominent investment banks active in the biotech space, we were able to look at the last 31 biotech IPOs that have passed their lockup expiry dates. These companies went public from July 2017 through April 2018.

The graph below captures the analysis. Relative to the stock price 30-days before the lockup expiry, there’s very little movement across the distribution of share performance. Best performing quartile of stocks actually move up 10-12% during the two-weeks straddling the lockup expiry date, relative to the month before. The mean and median are around +/- 5% during the period – which, if you watch these small cap stocks on a daily basis outside the lockup window, is really no different than during a normal two-week period of time. The bottom-performing quartile drops 10-15% relative to the month prior to the expiry. These data reaffirm the reality that new biotech IPOs are high volatility stocks.

These data suggest there’s really no discernible “systematic” effect on stock prices at or around the lockup expiry date, at least in this recent cohort of biotech IPOs. Looking at at longer Changes are much more company specific.

Frankly, if there were a systematic effect, the “market” would actively trade around it and extract returns from these trading dislocations – diminishing the opportunity over time. Perhaps there used to be a bigger effect in earlier IPO windows of the 80s/90s, which created the urban myth in the first place, but these data suggest that a systematic lockup expiry move is largely not present in today’s market.

What might some of those intrinsic, company-specific factors be that affect the trading behavior at lockup expiry:

- if the major shareholders are sitting on a great return already, do they try to sell more at a lockup (vs those with mediocre returns taking a wait-and-see approach)..

- if the major shareholders have lackluster returns at the current price, but think it could get worse, do they try to sell more at around lockup expiry just to get out…

- if it’s a young exciting company in a relative new VC fund vintage (vs an old tired company in a long duration VC fund ready to close), does that change a shareholder’s view of “going long(er)”…

- if there’s likely news flow or data in the near term after a lockup, do shareholders choose to wait for the upside (and upcoming data is always positive, as we all know…)

- if there’s a pending financing, or a financing overhang, do major shareholders decide to wait until after a follow-on financing to begin exiting their positions…

- if there are lots of potential buyers in the market, but no liquidity before the lockup, does the stock go up with expiry because now buyers can enter the market and acquire shares in the open market…

So many permutations. I’m sure there are many more.

But the conclusion remains: the boogeyman of a systematic lockup expiry downdraft on stock prices is largely a scary but unfounded urban myth. It totally depends on a company’s individual circumstances.

VCs, large shareholders, and management teams should try to proactively manage these intrinsic factors to ensure a smooth process on the road to building a strong public shareholder base. For more, see this post (“Biotech IPOs: The Exit Challenge As Lockups Expire“) from 2013 where a number of the themes remain relevant.