By Aoife Brennan, CEO of Synlogic, as part of the From The Trenches feature of LifeSciVC

I remember vividly my first vacation with the man who would be my husband. In the days before Airbnb and on-line travel websites, he had all the books and had thoroughly researched each destination, every transport option, all the food venues. The guy clearly had process.

In contrast, spontaneity was my compass. I tactfully broached the subject of maybe being more open to serendipity on our trip. He begrudgingly handed over his Lonely Planet full of page flags and told me I could choose where we would eat that evening. I flicked to the ‘Where to Eat’ section only to find he had already underlined and dated his top choice. If chaos is the law of nature; order is the dream of this man.

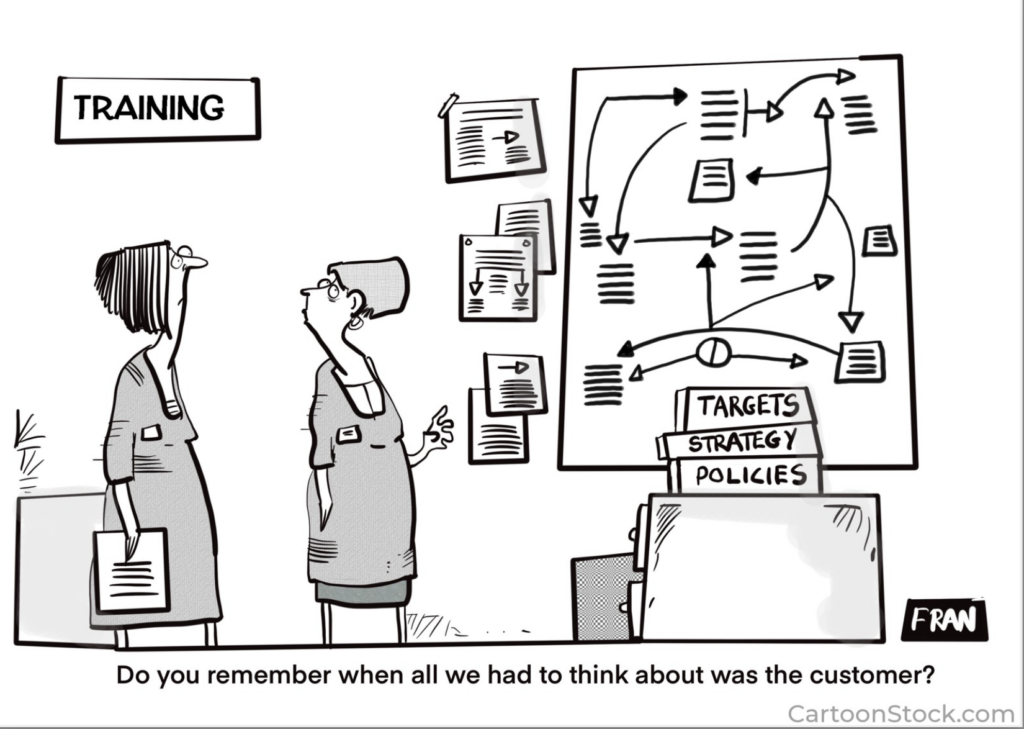

The question persists: how much process is too much when planning a vacation? This question, I’ve come to realize, holds relevance not just for wanderers but also for companies at all stages of their lifecycle. An oft-cited motive for biotech peers leaving their current roles is the aspiration to re-engage in the genuine work of scientific innovation and drug development, evading the trappings of bureaucracy in larger organizations. It can feel like fidelity to organizational processes supersedes the core mission itself.

Yet, an awareness of entropy pervades our collective consciousness. We’ve witnessed the disintegration of organizations and groups into chaos without the guiding hand of process and discipline. Creating balance in ensuring just enough process is a critical part of a CEOs role but there are few guideposts and certainly no one size fits all.

Reflecting on my seven-year journey at Synlogic, I’m reminded of our nascent days in drug development. The absence of standard operating procedures, project teams, or any concrete structure was palpable. Over the years, we’ve grown into a clinical-stage development organization, with our lead product candidate for PKU now undergoing a pivotal clinical trial. We’ve established a GMP manufacturing facility, weathered an FDA inspection unscathed, and introduced and revised processes along the way. This voyage has granted me ample opportunity to ponder the intricacies of process management and glean valuable insights.

Organizational process rheostat.

Within every team-member lies a distinctive process ‘sweet spot,’ dictating their preferred mode of operation. Some team members are naturally inclined toward structured approaches, while others break out in hives at the mere sight of a Gantt chart. Transparent discussions concerning the organization’s needs, transcending personal inclinations and past practices, are pivotal in securing buy-in and alignment with objectives.

Likewise, vigilance is paramount when individual functional units devise processes that others must adhere to without a collective understanding of the process’s overarching significance. We’ve encountered numerous false starts, instances of ‘process mutiny.’ We introduced a talent review process with the aim of streamlining and standardizing assessments, but it languished in obscurity—admired but unused.

Prudence in engaging external consultants is equally essential. Those unfamiliar with the intricacies of a company can institute processes that prove to be costly diversions.

The overarching aim of the CEO and management team should be determining what is right for THIS organization at THIS time.

Knowing when to let chaos rein and when to rein chaos in.

Andy Grove’s description of navigating this balance of process and agile innovation during his time as CEO of Intel resonated deeply with me. As companies mature and expand, an influx of process becomes inevitable. However, maintaining adaptability in the face of unforeseen developments is equally vital. In biotech change is the only constant. Processes and infrastructure that were built for a situation that is no longer relevant need to change just as quickly. Program discontinuations and staffing cuts can be easier to accomplish than killing the sacred process cow. Grove makes the case for allowing more chaos at times of uncertainty/pivot points.

Recognize that there is a cost to process.

The cost of lack of process and disorganization is often easier to spot than the cost of too much process. It can feel good to respond to a missed goal or some other negative business outcome with a new committee, a rigid process, frequent reporting. The cost of too much process when all those committees and reports compound is lack of agility, an avalanche of busy work and the alienation of the organizations most creative problem solvers. In the words of Nietzsche ‘you need chaos in your soul to give birth to a dancing star’.

I personally like the concept of ‘minimal viable process’ which involves being prepared to try things out, get feedback and reverse course on things that are not working. Minimal viable process will be unique to each organization and may also look different for different areas in the organization- we would never expect the research team to follow the same processes as the GMP manufacturing team. Ensuring that everyone in the organization understands why is an important objective of our internal communications and training.

To help ensure that an organization remains close to minimal viable process, it can be important to align on the timeframe under consideration when implementing new processes. I would advocate keeping that timeline relatively short, even at the cost of revisiting the process in less than 12 months. We recently upgraded our pharmacovigilance infrastructure but had to pull back when we realized a lot of the processes recommended by our vendors were only relevant for the post-marketing setting, which is still a few years away.

Achieving minimal viable process for vacation planning is still a work in progress for me. 20 years on and I continue to strive to take fantastic journeys that achieve balance between chaos and order. I occasionally get my way and discover surprisingly great places to eat.