The equity markets have collapsed in 2025, the IPO window is closed, the FDA is in turmoil, the NIH is being gutted… and it’s a great time to start new biotech companies.

Why? Because there are so few being created today and there’s far less competition for biotech’s startup resources.

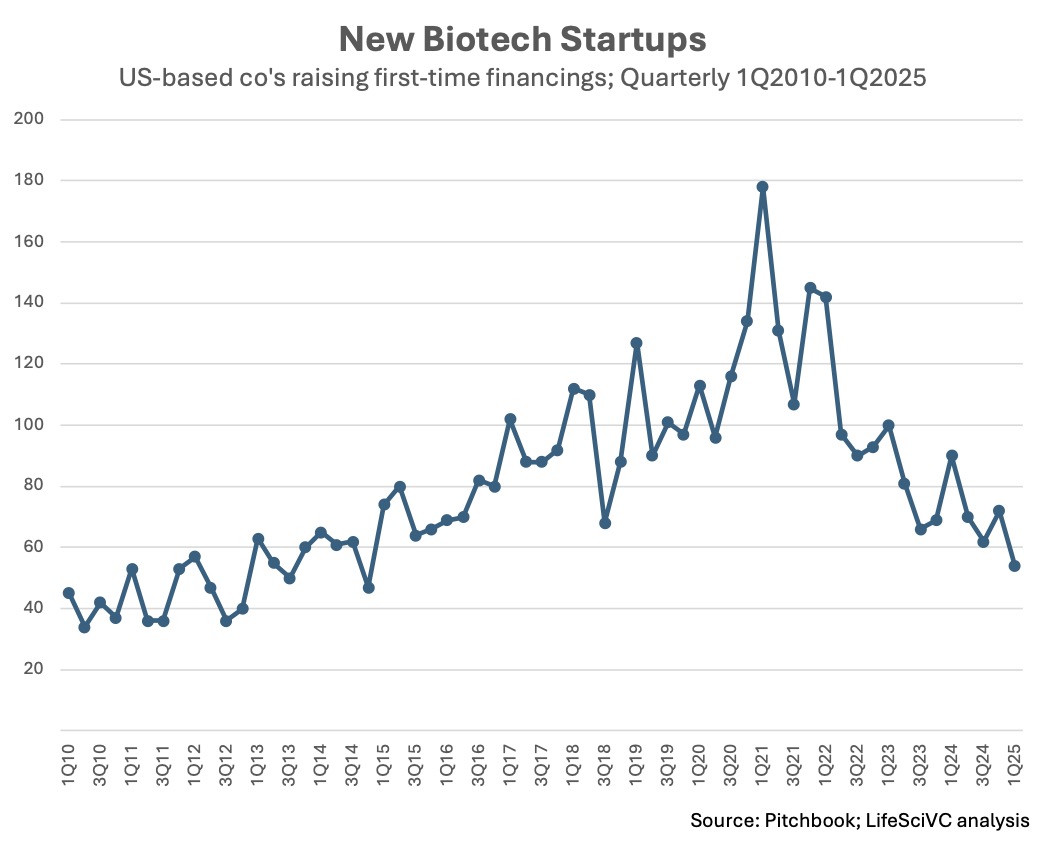

Here’s a snapshot based on the current cut of Pitchbook data: the 1Q 2025 was the lowest quarterly level of new biotech startup formation in the US for a least a decade.

This trendline downwards has been in place for four years, since the all-time-high in 1Q 2021 when the $XBI hit it’s peak, and this contraction was the subject of prior blogs in 2023 (Biotech Funding: Times Are Tough, Maybe For The Better) and in 2024 (The Biotech Startup Contraction Continues… And That’s A Good Thing), both of which highlighted the value of shrinking the pool of VC-backed biotechs. The pace of new startup formation is now down nearly 70%.

If the ecosystem is facing such headwinds, and public investors in particular are fleeing to safer havens, why do we hold the contrarian view that now a great time to start new biotechs? Because we’ve been here before: over the past twenty years as a venture investor, I’ve witnessed multiple investment cycles.

Taking a purely microeconomic viewpoint, startups operate in an “biotech equity” supply-demand environment. When demand to purchase new equity accelerates in frothier markets, tons of supply gets created: over 170 startups got their first financings in 1Q 2021. When demand contracts, supply shrinks: as it has over the past four years. But as a supplier – which venture creation firms like Atlas are – we’d much rather operate in a world of scarce supply as we create our “products”. When everyone is creating startups, hyper-competition for resources, patients, and mindshare is a challenge. But with scarce startup supply, when investor demand returns, which it will (as financial cycles are endemic to markets), we’ll see value appreciation: by providing a fresh supply of new equity ownership around promising drugs (with clean cap tables), founding/existing equity holders will be rewarded. Paraphrasing an early mentor of mine: as an early stage VC, you need to have an inventory of emerging investments for when the demand part of the cycle accelerates.

Beyond basic supply-demand economics, the three ingredients – or “resources” – required for VC-backed biotech startups are all very favorable today: science, talent, and capital.

Scientific substrate for startups is as strong and mature as ever. As a sector, over the past decade we experimented with and developed a broad toolkit of modalities to address specific drivers of disease with a wide range of therapeutic deliveries. We are now deploying the tools that work best in the context of new medicines addressing real unmet needs, by developing degraders, drugs based on covalency and allostery, genetic medicines, or multi-specific engineered biologics, to name a few. And we’re sourcing this startup substrate from all over the globe (from China to the Cambridges, from Italy to Indianapolis) to create NewCo’s, often headquartered in our backyard biotech communities.

The market for talent has loosened considerably; great leadership and strong managers are never easy to attract and retain, but things are far more favorable for recruiting teams than back in 2021. Voluntary turnover rates are at decadal lows, and the pool of available talent is deep (and filling with the unfortunate RIFs and belt-tightening). While there’s always a “war for talent” for the best teams, the “heat of combat” has come down considerably in this market.

Private capital remains abundant by historic measures, even if more risk-averse today, and more focused on assets than platforms. The first quarter of 2025 saw more than $5B in venture funding for biotech, and over the past twelve months there’s been $25B invested. Compared to the same annual period in 2017 and 2018, this is 50% and 25% higher amounts of venture funding, respectively. And it’s 300-400% higher than at the start of the secular bull cycles in 2013-2014. Every week there’s a new $100M+ mega-round being announced. So there’s plenty of dry powder, even though it often feels like firms are just sitting on it. While private valuations for emerging companies seeking Series B and later private rounds remain challenging, funding rounds are getting done (though taking longer to close). And those backlogged private companies waiting to go public need to weigh the deep discounts of raising in the private markets (and the significant equity dilution that implies) with the alternative of selling/partnering assets to strengthen their balance sheets. We’ve seen a number of those deals lately.

Stepping back and looking at these long-term dynamics when you are in the midst of the bear market part of the financial cycle is often very difficult. And for investors (and management teams) who are being judged on their monthly or quarterly returns, it’s brutal. These near-term challenges are not to be taken lightly as they have ripple effects and consequences. Redemptions to funds and capitulation to stock prices raises the cost of capital, sometimes beyond existential levels – as we’re seeing in the public markets today.

Big doses of discipline are important medicine for emerging companies to take right now: focusing on portfolio priorities, tightening budgets and belts, exploring partnership alternatives, considering creative mergers, etc….

Multi-year contractions like the one we’re in help to recalibrate the overall number of biotech companies. Flux in this ecosystem determines the equilibrium state: startup creation adds to the system, exits and failures subtract. Startup creation is down considerably, and while good exits are constrained (IPOs and mergers/acquisitions), failures have accelerated (shutdowns and liquidations/bankruptcies). So the “flux” favors a smaller overall ecosystem, though this process takes years to reset. Likes pigs going through the snake, biotechs work their way through the system. After four years of this prevailing flux dynamic, the private VC-backed ecosystem that remains is much healthier: the average health of the herd goes up with scarcity.

But it’s also important to remember that great companies are often born out of tougher times. Alnylam was started in the nuclear winter of 2002. Nimbus was formed in the spring of 2009, at the bottom of the markets. Kymera was being formulated in the late 2015/early 2016 bear market.

The startups that are being created today – the few and the proud – will likely be the emerging stars of 2030’s. It takes years to go from idea to clinical proof of concept in patients; unless you’re a startup being formed with existing drug candidates, it’s unlikely a de novo discovery startup will have true clinical PoC before the end of the decade (only five years away). As an early-stage venture investor, a core part of our job to help enable these future winners – by creating, funding, building and scaling the next generation.