This blog was written by Brian Fenton and Paul Burgess, CBO and GC of RaNA Therapeutics, respectively, as part of the From The Trenches feature of LifeSciVC.

On April 18, 1775, Paul Revere was summoned by Dr. Joseph Warren of Boston to ride to Lexington with news that British regulars were marching into the countryside north of the city. A seemingly daunting task, Revere crossed the river into Charlestown, mounted a borrowed horse and began his famous trek. Fast forward to 2016, and another daunting task unfolds: A small biotech across the river from Boston sets out to acquire a promising asset from a global pharma with U.S. headquarters in Lexington. The former begins the story of the American Revolution, and the latter…perhaps a new revolution in mRNA therapeutics.

Code-named “Project Patriot”, the deal had been months in the making at RaNA. And except for the press release, the details of the likely exciting moments, urgency and inevitable roadblocks needed to be surmounted in any deal will remain hidden like the secrets lost in that daring ride. And as we know with all significant deals (which are no small miracles when they happen), corporate development is a team sport that requires close coordination and execution at all functional levels to be successful—the idea of any lone rider solely responsible for getting a deal done is as romantic as Longfellow’s thrilling poem.

But what is public is that earlier this year RaNA announced what could be a truly transformative deal for the company by acquiring Shire’s messenger RNA Therapy (MRT) platform. In addition to this asset, RaNA welcomed Shire’s former MRT employees – a group focused on the development of the technology since 2008 – and acquired two late-stage preclinical programs in cystic fibrosis and OTC deficiency, the most common urea cycle disorder. With the acquisition, the company is now highly focused on mRNA therapeutics, significantly expanding its ability to correct a wide range of disease genotypes and access new targets not currently addressable by existing technologies and modalities. As part of the agreement, Shire got an equity stake in RaNA and is eligible for future milestones and royalties on products developed with the technology.

Acquiring Mature Technology in Biotech

Most biotech M&A transactions are from the other side – think Allergan’s recent acquisitions or Pfizer’s Medivation win in 2016. Far fewer are deals where biotech companies acquire mature assets from pharma, but just as Bruce noted towards the end of last year, early stage deals are heating up as the demand for innovation grows and Pharma looks to de-risk its platforms and externally enable more of its pipeline candidates.

Biotech companies, too, are on the hunt for ways to expand growth and resources. While most start-ups develop technology from an early stage or license IP from a university, some start-ups acquire mature technology from large pharma or another biotech company. One the of challenges with out-licensing mature technologies is finding the right balance for the investors and the out-licensing companies. From a big company perspective, it is certainly easier just to kill a program than to take the time and effort to out-license it. An out license requires the approval of the scientific organization, legal and sometimes HR if people go with the technology. Documents must be identified, separated and transferred. Legal and business development must draft documents, undergo IP and scientific diligence and negotiate a deal. An out-licensing company certainly has to believe in the technology to undergo such a process, but as described below, when the investors and the out-licensing company get it right, there is a lot of upside for all parties involved.

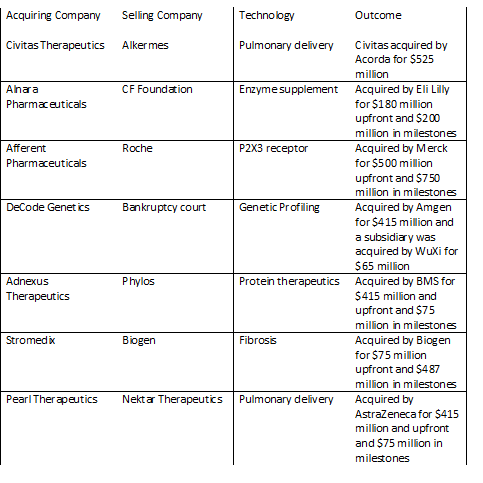

Civitas is a great example of using a mature pulmonary technology to quickly advance a product and lead to a successful exit. Alkermes had spent about 10 years developing its pulmonary drug delivery technology, but hit a point at which the technology was no longer core to the company plans. Civitas was formed in 2010 and acquired the technology, inhalers, manufacturing and products from Alkermes. Alkermes kept an equity stake, milestones and royalties in the ultimate products. Over the course of less than four years, Civitas raised $118 million and completed a successful Phase 2b trial in Parkinson’s disease. In 2014, Civitas was acquired for $525 million at about a 4.5-fold return for investors.

Adnexus Therapeutics and Decode Genetics are additional examples of mature platforms which were acquired from bankruptcy and resulted in favorable venture capital return. Adnexus, which was originally called Compound Therapeutics, acquired its Adnectin technology platform from Phylos out of bankruptcy. Adnexus advanced that platform and was acquired by BMS for $415 million upfront and $75 million in milestones about three years later. Decode was over ten years old when it went into bankruptcy. The company was funded again out of bankruptcy and was acquired by Amgen three years later for $415 million.

Another interesting example is the case of Alnara. Alnara acquired a mature enzyme replacement product which had previously been under development at Altus and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. In about two years, Alnara raised $55 million, conducted a successful phase 3 trial and was acquired by Eli Lilly in for $180 million upfront plus additional milestones (over a three-fold return on investor cash).

A few examples of a longer trajectory include Afferent Pharmaceuticals and Pearl Therapeutics. Afferent was started with some P2X3 antagonist compounds from Roche. After seven years and about $75 million raised, Afferent was acquired by Merck for $500 million upfront and up to $250 million in milestones. Pearl Therapeutics was a spin out of Nektar with a pulmonary drug delivery technology. Pearl raised about $170 million over seven years and was acquired by AstraZeneca for $415 million upfront and $75 million in milestones.

Finally, Stromedix is an example of a boomerang type deal. In these type of arrangements, a larger company licenses a product to a smaller company to advance beyond a certain stage and then takes the product back. In the case of Stromedix, Biogen licensed an antibody for fibrotic disease to Stromedix. Stromedix raised $38 million before Biogen reacquired the company for $75 million upfront and $487 in milestones.

Recent spin outs

The Promise of mRNA Therapeutics

To give more context to the RaNA/Shire deal, it is useful to review the promise of mRNA therapeutics. The last few years have seen an explosion of interest in in this area as a therapeutic modality. The ability to send the body instructions to produce its own drug is a compelling concept so elegant that it seems almost too good to be true, but undoubtedly, could be transformative for the field of medicine.

The idea of delivering mRNA to encode protein production in an animal dates to the early 90’s when direct injection of various mRNA reporter genes were first used. In 1992 it was shown mRNA encoding for vasopressin could reverse diabetes in a rat model via intrahypothalamic injection. The nascent mRNA field however was plagued early on by manufacturing, delivery, stability, targeting and other challenges, such that the field was somewhat deprioritized by researchers in favor of developing DNA based technologies including plasmids and other viral vector delivery systems.

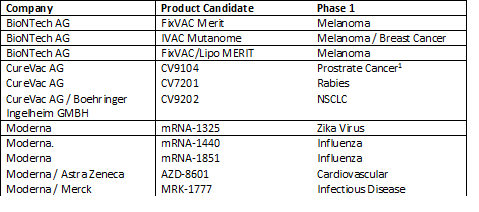

In the last five years, however several of those challenges have been addressed, at least initially. An early pipeline of product candidates, overwhelmingly in infectious disease and cancer vaccination, has emerged with innovators and their partners betting that the technology provides a better immune response than can be achieved with recombinant protein coupled with adjuvants or DNA-based vaccines. The broad therapeutic potential of mRNA is still, however, very early in development with only AZ/Moderna thus far disclosing something other than a vaccine in the clinic.

mRNA clinical pipeline*

1CureVac announced CV9104 failed a Phase IIb monotherapy trial in January 2017

1CureVac announced CV9104 failed a Phase IIb monotherapy trial in January 2017

But as evidenced in the over $2.5B raised by companies in the field through financing or early partnerships, interest has remained strong over the last few years.

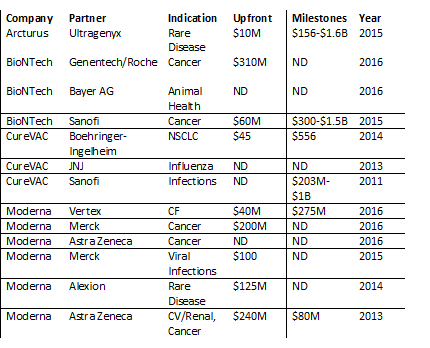

Major Deals in mRNA Technology*

But with any emerging field, many challenges still loom. Delivery for instance, remains a key area for improvement in the field just as it was for anti-sense oligonucleotides until galnac conjugation technology pioneered by Alnylam demonstrated success in subcutaneous administration of RNAi gene knockdown in the liver. In addition, much like we have seen in the gene-editing space, the mRNA field has seen some recent IP saber-rattling, particularly around LNP (or lipid nanoparticle) delivery.

RaNA believes it’s mRNA technology is different than the competitors. While most of the field has focused on vaccines, RaNA scientific team has been working on mRNA replacement therapy for almost 10 years (along with a smaller amount of vaccine and other work). Through this process, the company and its academic collaborators believe they developed key advantages and learnings in mRNA delivery and manufacturing. While RaNA uses a variety of sequence modifications to increase expression, the technology does not use chemically modified bases. The company believes these and other attributes are critical for advancing into the clinic. And yet while in many respects still in its infancy, the promise of what mRNA therapeutics offers us is an exhilarating glimpse of what could be the dawn of a new era of treatment for many.

And although the gun battery at Fort Washington Park in Cambridge, MA (the oldest surviving fortification from the American Revolutionary War) remains silent after almost two and half centuries, just around the corner in a former Vertex building, RaNA has been busy positioning its newly acquired mRNA arsenal towards the clinic. With Project Patriot complete, the company aims to file an IND by year end on what could be the first mRNA-based therapeutic for the treatment of all cystic fibrosis patients regardless of mutation. And with the biotech’s anticipated first shot into the clinic, it’s very likely RaNA will find itself on the front lines of another revolution in medicine. And just as it did in 1775, the road begins across the river from Boston.

* Summarized from industry sources