M&A is an omnipresent reality in the biopharma industry, from Big Pharma mega-mergers to smaller acquisitions of emerging startups.

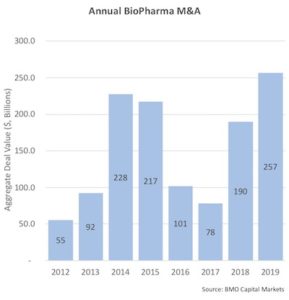

We’ve recently witnessed several large M&A transactions get closed or announced, including BMS-Celgene, Takeda-Shire, and AbbVie-Allergan; according to BMO Capital Markets data, there was nearly $260B in M&A deal activity in 2019. Over the past eight years, we’ve seen over $1 trillion in M&A deal values in aggregate.

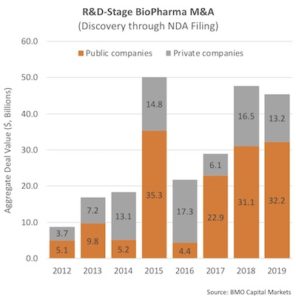

For R&D-stage M&A events, more relevant to the loss-making biotech universe, we saw $45B in 2019, similar to the boom years of 2015 and 2018. This year is off to a good start with Gilead’s $4.9B acquisition of Forty Seven Inc announced today, among others.

In short, we’ve seen a huge amount of overall deal activity in the biopharma space in recent years.

While high profile biotech acquisitions are often celebrated as wins, rarely are the bigger mergers viewed favorably. Pundits and policymakers often claim these larger M&A deals do a myriad of bad things: destroy value, distract R&D groups, consolidate market power, take out emerging competitors, and negatively impact drug pricing. The recent dissenting opinions on the BMS-Celgene merge from two FTC commissioners highlighted this perspective, as both were against approving the deal because of the possible negative competitive impact.

Most academic analyses of big mergers focus on the impact to the merged company itself: what happens to R&D spend, what happens to employees, etc… Often these analyses conclude the deals were “bad for innovation” (here) by reducing the combined R&D activity at the merged entity (or even competitor firms).

What these analyses fail to consider is the overall ecosystem benefits of M&A activity – a crucially important aspect that needs to be better appreciated by politicians and policymakers in Washington: fundamentally, large and small M&A deals, on the whole, help catalyze a more efficient allocation of scarce resources across the sector, especially over the longer term.

Before diving into why that’s the case, some additional background is warranted.

First, relative to many R&D-intensive industries, Pharma is incredibly fragmented. No single player has more than 10% market share in most broad market categories, including across sales metrics and R&D activity metrics. Further, we have hundreds of thousands of researchers on big and small R&D teams chasing the scores of new and established targets and developing new drugs against them. Failure rates are extraordinarily high, as we all know – and the cost and time to bring a drug forward remain significant. Once on the market, we also have a huge number of sales representatives, or specialty medical affairs folks, out in the clinical community trying to convince physicians of a drug’s merits. All of this leads to massive redundancy and hyper-competition on the highest impact approaches. It’s easy to argue there is frequently a temporal misallocation of talent, science, and capital resources at the industry level (see this blog’s commentary on oncology’s concentration from 2012 and 2016).

Second, there’s also a massive difference in the “cost of capital” across different players in the sector. This means there’s a huge difference in the ability of players to fund the long journey from idea to full market commercialization. The larger profitable biopharma companies have a cost of capital near zero – they have significant cash flows, large balance sheets, and can raise low interest rate debt at will. Contrast this to the loss-making biotech world, where access to new capital (funding) is always an issue. Even in the latter group, there’s a huge range in the cost of capital from startups (very high) to pre-profit “small and mid cap” biotech companies. As a sector, allocating our capital (and, by extension, our talent and science resources) efficiently is critically important if we are to keep investors involved the space versus moving their capital to other sectors.

Lastly, the steady rise of emerging biotech over the past few decades as a powerful force for innovation is well accepted: more drugs are being discovered by smaller firms than ever before, as evidenced by the increasing proportion of active INDs and new drug approvals (NDAs) attributed to smaller firms. The biotech phenomenon of the past decade, with stock market indices up ~500% since 2010, has been heralded as the “golden age” of biology and medicine. While there are many contributors to this biotech success story, one of the unsung heroes has been the steady march of M&A deals in our ecosystem as a tool for efficiently (re)deploying resources.

In short, M&A has helped address some of our ecosystem’s redundant and bureaucratic inefficiencies, like those highlighted above, by helping the sector better allocate the scarce value-creating resources of talent, science, and capital over the long term.

Talent

Every big and small merger contributes to the fluidity of the biopharma talent market.

In the five years between 2009-2013, according to the Wall Street Journal, Big Pharma companies shed at least 156,000 American jobs. Many of these were in R&D, and many of those individuals moved into emerging biotech firms, CRO partners, or other players in the biopharma ecosystem. The disruptive impact of M&A integration on a merged company’s organization is almost certainly real, but as a sector it should be offset against the benefits of bringing catalytic new additions into the talent pool – either into younger biotech firms or cross-fertilizing with other Pharma organizations.

As I’ve written before, talent acquisition from Pharma is the lifeblood of startup biotech. Most of the executive teams around the industry spent some time in large Pharma companies. By my quick estimate, more than 90% of our three dozen CEOs spent some time in their careers in Big Biopharma companies. These experiences are important, and contribute to the grey hair in the C-suite that enables better judgement.

Thinking of the Boston, the diaspora of biopharma executives from acquired firms has been essential to the success of the cluster; for example, when Genzyme, Millennium, and Wyeth/Genetics Institute were acquired by Sanofi, Takeda, and Pfizer, respectively, it prompted a significant migration of talent about a decade ago. We’re seeing that now with former Shire and Celgene teams in the Boston area. The same is true in other geographic clusters, with talent movements from acquisitions of Genentech, Immunex, IDEC, OSI, Tularik, and many others over the past two decades.

Of course, talent movements occur without mega-mergers and big M&A events as part of ‘normal’ talent turnover. But M&A creates temporary but significant dislocations that certainly enhance the local volume and overall fluidity of the talent market.

Smaller M&A deals, which are much more frequent, are also crucial for these talent flows – contributing to the recycling of serial entrepreneurs to seed new teams and startups. Many of our current portfolio executives came from prior M&A exits at Padlock, Nimbus, Stromedix, Arteaus, etc…

In short, by liberating talent to find new opportunities, large and small M&A alike help create liquidity in the talent market. This liquidity better matches prospective candidates’ skills with companies’ capability needs – which over the long run creates a more efficient deployment of talent across the ecosystem.

Science

M&A also has a dramatic impact on the scientific portfolios of the post-merger entities. It certainly changes the critical filters for evaluating programs, and almost always alters R&D capital allocation decisions. As described well by others, two simple ways to improve R&D productivity are to (a) start projects based on better science and (b) improve decision-making around what programs to allocate capital to. M&A can and often does help with both of these areas.

In the case of mega-mergers, the integration of two predecessor companies brings a new lens to program and portfolio prioritization. Fresh eyes with less familiarity or confirmation bias can often lead to better (or at least different) decision-making about what science to fund vs kill, and what projects to start. New reviews also deprioritize drug programs that are either below the bar in their opinion, or are in disease areas outside of the scope of the newly merged entity. Some of these ‘deprioritized’ assets remind me of the phrase that “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure”: differences of opinion on the merits of different programs is part of the science shuffle that occurs after mergers.

Thankfully, with the rise of external R&D models over the past two decades, these potentially interesting or off-strategy assets are often spun-out to other Pharma companies or emerging biotech portfolios. Some will even have new startups nucleated around them. The number of biotech companies with ex-Pharma assets as their lead programs is strikingly large, and these programs are often liberated through post-merger scientific portfolio reviews.

Again, like talent, there’s a natural cadence of spinning out assets during ‘normal’ periods of portfolio assessment that gets significantly amped up by M&A dislocations. It’s fair to say that lots of VCs and entrepreneurs are hungrily pouring over (or awaiting lists of) out-licensing opportunities from Takeda, AbbVie, and BMS following their recent acquisitions.

Acquisitions of smaller biotech firms can also help deploy science more effectively. Most startups are constrained by their capital base, so doing broad and expansive Phase 2 or 3 campaigns is incredibly challenging. Most startups don’t run half a dozen parallel Phase 2s in different indications with a single program; cash-rich Pharma does this all the time. So biotech M&A can put exciting assets into larger organizations who are much more resource-enabled for bringing them to the broadest patient population around the globe in the fastest possible time.

These are a few perspectives of how M&A can lead to a more efficient advancement of scientific substrate at the industry level.

But beyond just bringing assets into new organizations, these M&A transactions put science into the hands of new organizational champions – those protagonists who are deeply committed to bringing the scientific programs forward to patients and the market, like John Hood with fedratinib. Without passionate champions, projects don’t make it through R&D gauntlet and into new approved drugs, at either small or large companies. The combination of a more fluid talent and science marketplace helps advance these new potential drug candidates by more efficiently aligning them with new passionate leaders.

Capital

M&A events liberate a lot of investor capital that recycles back into the ecosystem.

The scale of this recycling from M&A is mind-boggling. Geoffrey Porges at Leerink estimated in July 2019 that nearly ~$180B in cash was returned to investors via M&A over the prior 12 months – in comparison to less than $30B in equity financings (IPOs, Follow-ons) over that period. Porges’ conclusion is one that I also share: “…the magnitude of these liquidity events could explain the surprising durability of the capital markets cycle in the sector.” When cross-sector fund flows into biotech have been stagnant (as we’ve seen with the puts and takes of fund flows in recent years), one of the major buyers in the equity capital markets are healthcare funds that are redeploying cash from portfolio M&A events into new purchases of equity issued by biotech companies.

The recycling of capital from these M&A events has several effects worth calling out specifically.

First, M&A sends cash back to a large number of institutional public investors, which of course increases the availability of funding for cash-burning companies. This makes it easier for later stage biotechs to issue equity in the public markets, as well as in pre-public crossover rounds.

Second, M&A sends “realized returns” back to the Limited Partners of VC funds, helping the latter report better IRRs and investment multiples, which over longer cycle times increases the interest of LP’s in the space. Historically the ugly stepchild of Tech venture capital, Biotech has never seen LP interest in the sector as strong as there is today. This means raising biotech venture funds is easier, and this increases the supply of venture capital funding available for new startups and younger private biotechs. In line with that, venture capital funding into private biotechs has risen 3-fold in the past eight years, to a run rate of $20B+ per year.

Both of these effects work to dramatically reduce the cost of capital for innovative biotech companies across the spectrum – from new startups to SMid-cap pre-launch biotechs.

By freeing up capital, often from illiquid private or thinly traded public stocks, M&A enables investors with the opportunity to reassess where they’d like to deploy their capital – thus improving the liquidity and efficiency of capital allocation across the sector. Innovative projects are able to attract more capital in this environment, and are afforded with a lower cost of capital in the process.

—

Large M&A events in biopharma are frequently viewed with negativity, by both academic critics and government policymakers. These transactions certainly can create significant disruptions for the merged entity, with potentially negative impacts on that firm’s R&D productivity.

But the beneficial impact of M&A on the overall biopharma ecosystem is profound and should be better appreciated by those involved in policy: in short, by improving the efficiency of allocating the scarce resources of talent, science, and capital across the sector, M&A drives huge benefits – and much of biotech’s current success in advancing innovation stems from these long term positive impacts.