Not a biotech conference goes by these days without a discussion about new models for financing or exiting companies, and BioPharm America in Boston this week is no different. I’m on a panel discussing the topic on Wednesday afternoon.

New models come up all the time because we’re an industry in the midst of dynamic change and adaption: changing (and shrinking) mix of venture funds, increasing role of corporate venture efforts, largely inaccessible IPO markets, LP (mis-)perceptions about Life Science returns vs Tech affecting asset class allocations, fund size math pressures, the capital efficiency imperative, etc… Many of these topics have been discussed before in this blog, but I thought I’d revisit the “new model” subject to provide some practical points and examples.

But before that – some context: generally speaking, there are two conventional models for biopharma companies: either drug discovery platforms or product-focused plays. Broadly, these two approaches were reviewed in a prior post on “worldviews” of biotech that framed up some of the key success factors.

To recap some of the challenges with those, it’s clear that both have struggled with industry-wide issues around capital intensity (burn rates) amidst stubbornly high costs of capital. This can only be managed through tighter titration of capital, focused on derisking the story, while seeking non- or less-dilutive sources of funding to take it forward (like accessing big balance sheets of larger partners).

But there are also some very specific challenges to each model. Drug discovery platforms require significant money and time to build, but are frequently only valued for the lead products that they produce and only after they’ve made it into the clinic; in a world where exits are only M&A driven, this greatly handicaps the value of the platform itself, delays time to liquidity, and hence diminish returns. Product plays have typically been roll-ups or spec pharma stories, where portfolios are accumulated under the pretense of product diversification and efficient use of a “management’s bandwidth” – but the crispness of a tight product thesis is often eroded, suboptimal assets consume resources (lemons being outlicensed by Pharma), and the eventual value of the story focuses on a single lead program over time.

These challenges are in large part due to a singularly company-centric view of investing, building, and realizing value that remains commonplace today. But by taking an asset-centric view of both types of models, a number of these concerns can be alleviated.

Here are a few practical thoughts on two asset-centric corporate structure models to platform and product plays.

Drug Discovery Platforms: LLC Holding Company Model.

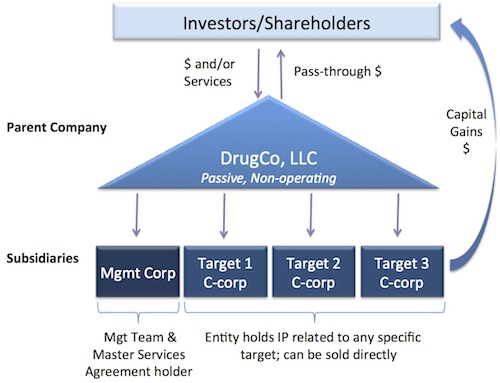

Instead of building drug discovery plays as singular entities (simple C-corp), we believe that taking a more modular approach to discovery engines through the creation of LLC holding company structures can optimize value. The figure below captures the set up:

Here’re the key elements to the structure: The LLC itself is passive and non-operating. This makes for a more tax efficient model for institutional investors (a straight LLC can work well if individual investors are involved rather than VCs). The team and the technology platform itself are housed in a subsidiary C-corp (“Mgmt Corp”), which sets up all the Master Services Agreements and such. Each drug program, right before generating valuable IP, should be moved into its own C-corp subsidiary of the LLC – the data packages and IP related to a program are all housed in their own entities. A variant of this subsidiary model is to put several related programs into a single subsidiary – assuming that the “exit path” for that basket of programs is the same then this makes sense.

Liquidity can be driven through all the traditional manners (M&A of the whole thing, or an IPO), but the real virtue of the model is that single assets can be monetized to create returns without losing the platform: as a program matures and garners Pharma interest, that single subsidiary can be acquired by the partner in a risk-sharing, earnout-based structure. The payments flow into the LLC as capital gains (since it was the purchase of equity), and can be passed through to the shareholders of the LLC. The Board of the LLC can determine how much gets distributed vs recycled into new drug discovery operations.

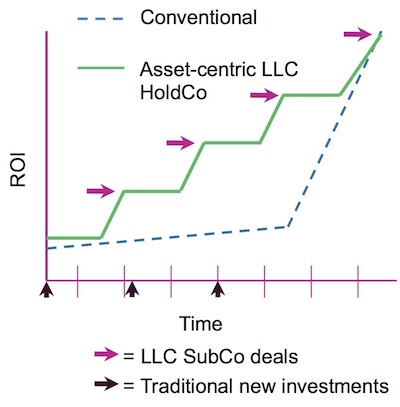

Compare this LLC return profile to a traditional drug discovery company with the illustrative chart below. The dotted line below tracks the relatively flat valuation typically given to a drug discovery biotech over its Series A/B/C rounds; then, like a hockey stick, if things go well it exits at a great multiple. This illustration is realistic: both Avila and Adnexus had flat/slightly down Series B rounds only a couple years prior to their big exits. Now take the green line, illustrative of the LLC model: each asset sale incrementally improves the ROI, and “smooths” the curve over time as deals around Dev Can or IND mature more quickly than waiting until mid-clinic results to catalyze a big exit. So the aggregate return curve and flow of capital looks far more interesting.

More importantly, this model also enables the potential for an ‘evergreen’ biotech model – since you don’t have to sell the entire company to generate returns, and you don’t need to take a company public to get liquid, this LLC holding company model enables you to invest, build, and harvest returns out of a drug discovery engine over much longer time frames. It’s easy to argue for “going longer” when you’re sitting on healthy return already. This feature certainly has real appeal to many management teams that want to build a lasting company in the current ecosystem.

It’s worth noting that nothing is free, so this structure costs something. Care must be taken to track the flow of funds for accounting reasons across these entities – which requires more sophisticated finance expertise. You also need more lawyer time to get this structure in place and maintain the appropriate governance. But these costs are dwarfed by the potential benefits.

This model is more than just a good thing to talk about at conferences: at this point, all of our recent discovery plays at Atlas have adopted this model. We pioneered the structure with Nimbus Discovery LLC in 2009, launched RaNA Therapeutics LLC in 2011, and stealth-stage Boreal Therapeutics LLC in 2012. Other drug discovery plays like Forma and Viamet (non-Atlas deals) have been convinced of the value of this LLC approach, and have reorganized from C-corps into LLC’s due to the clear advantages of the structure. I suspect that most drug discovery plays will move towards this model over time.

Product Plays: Single Asset Project Financings with Structured Buyouts.

Single asset project financings aren’t new news; we and others have been investing in these types of deals for years (e.g., Stromedix, Zafgen, Infacare, and others). By creating a portfolio of these approaches we are able to balance the binary risk profile of these companies.

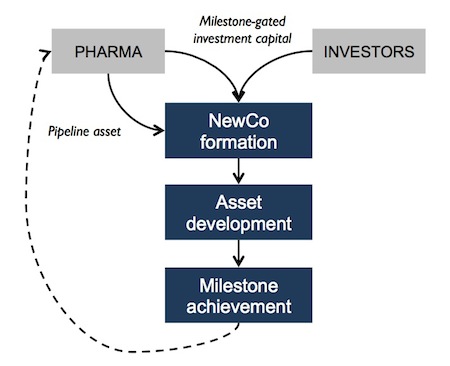

A more recent trend shaping our view of project financing models has been Pharma’s increasing interest in finding creative P&L-sparing means to fund more R&D efforts externally, especially in the context of shrinking internal budgets. This dynamic, coupled with the increasing sophistication and specialization of the CRO ecosystem, has enabled the creation of single-asset deals with defined liquidity paths via structured buyouts.

Here’s the “simple” description of how these deals get done: Pharma has a handful of assets it believes are interesting but can’t be funded due to budget constraints. These assets are typically not on the out-licensing list per se, because the Pharma is interested enough to want them back if they work; most pure out-licensing plays are sour lemons (though many biotechs have made lemonade). The Pharma then opens up its kimono and shares the profiles of these interesting assets and their development plans with us. We do our diligence on those, share an “open market” view of the strengths/weaknesses (which most Pharma’s have found valuable), and then identify one or two we’d like to push forward on. We typically bring in a team of experts to rework the development plan with a lean, fast-to-PoC project-financing mindset. At that point, assuming we like the way its coming together, we negotiate a pre-defined exit path for a possible investment: upon successful completion of XYZ clinical study, the Pharma will buyout the asset-centric entity in an upfront plus milestones type transaction. For Atlas to consider a deal, the upfront plus near-term milestones needs to generate the potential for a top decile outcome (>5x); longer term milestones and royalties help secure outlier potential if the drug makes it to market. We also need to customize the deal’s more nuanced attributes: the accounting and tax structure of the deal, the nature of the IP transfer (or not) to the new entity, what to do in different “grey” outcomes, timing of specific financings, etc… Then the final proposal with all the juicy details needs to be approved by the right internal decision-making committees at the Pharma partner. All this takes a lot of time, lots of time, and with lots of potential for frictional loss. But, once completed, we think they make for very interesting deals for both Pharma and for Atlas.

We set up our Atlas Venture Development Corp (AVDC) initiative to push these types of deals forward back in 2010, and our Shire Alliance in 2012 is a variant of this theme. Several other groups have recently announced efforts to also seek deals of this type, including CMEA’s Velocity initiative. I’m not sure how many have been done in total across the industry, but to date we’ve closed two such transactions.

Arteaus is working with Eli Lilly on an anti-CGRP antibody for migraine prevention, and is in the midst of its clinical proof-of-concept study. Upon successful completion of that study, Lilly has the right to acquire Arteaus in order to pursue the antibody’s further development. This project raised an $18M Series A financing to complete Phase 1a, 1b and 2a; OrbiMed joined us in the financing and things have gone well so far.

More recently, Annovation struck a similar structured deal with Medicine’s Company (MDCO) around a novel anesthesia asset. In this case though, we actually sourced the asset from Partners and during the seed funding secured the relationship with MDCO as a natural buyer.

Since starting AVDC, we’ve reviewed well over 200 opportunities and only closed two. Our Shire Alliance has reviewed over 100 assets, and is actively evaluating a few maturing opportunities; we’re hopeful we’ll have more to announce by yearend. Reality is that it’s not easy to get these deals done – patience and creative problem solving are some of the most important ingredients.

But when done well we think they address a number of the issues that plague product-focused biotech plays – they offer a pre-defined and tightly-titrated capital intensity, a virtual development efficiency, and a clear path to liquidity in a reasonable timeframe.

Looking forward to discussing these and other “new models” at BioPharm America on Wednesday.