Macrocyclic drugs are an emerging class of therapeutics that promise to open up drug target spaces which are poorly addressed by small chemical entities and larger biologics. Cyclosporin is the classic template of such a drug: a cyclically constrained peptide with modifications to both its backbone (N-methylation) and selected side chains (“non-natural” amino acids). Cyclosporin’s unique attributes of facilitated oral delivery and intracellular targeting have make replicating its profile the holy grail of most macrocycle concepts.

In the past five years, more than a dozen companies have been funded under the premise that they can rationally design or screen for “cyclosporin-like” macrocyclic drugs to find uniquely differentiated therapeutics, including Aileron, Bicycle (where for full disclosure Atlas has invested and I’m on the Board), Ensemble, Peptidream, and Ra, among others.

In September, first SciBX Summit on Innovation in Drug Discovery & Development was convened to tackle the challenges that face the development of these macrocyclic drugs and “puzzling out the basic science underlying these molecules”. They also wrote up an outstanding review of the Summit and space in last week’s SciBX (free pdf download here); for those interested in the space, this is a must-read.

Since they’ve already done a great job summarizing the four major challenges, I thought I’d just reiterate them and then move to the biggest question of all. Here were the four major challenges that need to be overcome for the next wave of macrocycle R&D efforts to be successful, which were cited by the Summit and articulated in the SciBX piece: improving pharmacokinetics (serum half-life, tissue exposure); understanding cell permeability; achieving oral bioavailability; and understanding their binding modes.

These are serious challenges. So why have (and why should) venture investors bother channeling capital towards macrocycle plays? Because this modality could be big. Macrocycles offer a number of advantages over bigger biologics, including better ligand efficiency, tissue penetration, delivery, and cost. And versus conventional small molecules, they offer improved selectivity and larger binding modes (useful for PPIs), among others. But this new wave of programs will only be big – and individual deals will only be successful – if their team’s figure out how to channel scarce resources into pursuing the right differentiated applications. Like most drugs, the key will be to differentiate them from known modalities (and other macrocycles), and this will fundamentally depend on a target-by-target, disease-by-disease analysis.

This strategic target selection question is paramount for all new modalities: if you pick targets that are “well validated” in order to stay with “low risk” opportunities, you may win the battle but not the war: you prove the modality works but poured funding into a program that lacks lack significant differentiation or at the very least faces crowded classes. If you pick targets that are too hard or too risky, then you could end up never proving that your platform is worth anything. This target choice tension is evident in every early stage platform company that I’ve been a part of, and can be a huge value driver or value destroyer.

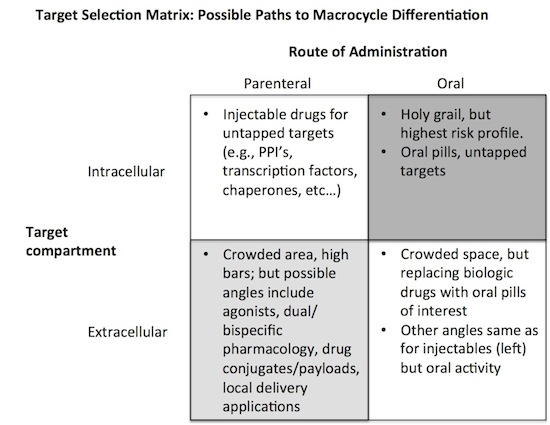

At Atlas, back in 2008 when we were initially evaluating the macrocycle class, we felt the “differentiable” target space was best approached with this matrix:

Obviously the most exciting applications would be for macrocycles that are orally active, cell penetrant drugs that open up totally novel, untapped targets. But its also the most high risk, and the challenges, as highlighted by the Summit, make this unlikely to be low hanging fruit any time soon. However, if it could be done, this quadrant would certainly deliver on the high cost of capital demanded by venture investments in the space: this is high risk, high return domain.

At the opposite corner are the injectable macrocycles that have to compete in the extracellular space. It’s a high bar here, and while the risk is low, the opportunity set is constrained. Just another injectable approach to the same set of well known serum proteases or cytokine targets is simply not that interesting, nor are most locally administered versions. The only realistic way to achieve a venture return on these approaches is creatively demonstrating what is likely to be a narrower differentiation profile. Here are a few: agonist approaches are tough to do selectively with other modalities and might work well here especially with shorter PK profiles; dual-acting macrocycles, engineered to hit two targets selectively, could open up more cost-effective and tunable bispecific functionality; lastly, conjugating toxic payloads onto macrocycles may prove more interesting than ADCs if they provide better tissue and tumor penetration, as well as clear stoichiometry, than bulky biologic approaches. All these are theoretically differentiable profiles, but the killer experiments around these and other angles are being done now by many macrocycle startups.

The other two corners of the matrix are somewhere in between with regards to their degree of both risk and opportunity. The top left quadrant offers access to truly novel target biology with an injectable drug, which is an interesting mix. The reliance on an injection for delivery shouldn’t impair its product profile if the biology is truly distinctive. In some ways, this is one of the quadrants with the best balance of risk and opportunity given the obstacle of high oral activity.

At the bottom right, orally-active compounds against more conventional extracellular targets is a tricky one. Is simply making an orally available anti-TNF or anti-IL17 interesting enough? If its as efficacious as a marketed mAb, then of course as it will also have big cost-of-goods advantages. But is that a bet whose risk is dischargable early in development? Probably not. This is a big challenge for venture investors to wrestle through. Oral active versions of the narrower differentiation profiles mentioned above (agonists, dual pharmacology, conjugates) could be interesting, but gastric stability and adsorption may preclude those from working optimally and may conflate the risk profile.

In the long run, solving the challenges that the Summit laid out (PK, permeability, oral bioavailability, and binding modes) will be key to this class delivering the big therapeutic impact we all hope to witness. But in the short-run, getting some early points on the board with other more modestly differentiated approaches will be important markers of success for the next wave of molecules around the macrocycle modality. Getting the balance right between these short- and long-run product aspirations, and the investments required to get the field there, will be of critical importance. Hopefully at least of few of the current crop of emerging startups in the space will successfully address these challenges.