Biotech is definitely red-hot, and has been for the past eight quarters. Immuno-oncology, cancer metabolism, gene therapy, orphan diseases, NASH, autoimmune – there’s a broad range of disease settings that are capturing the excitement and imagination of investors today.

With some sky high public market valuations, the big question is whether this is “hype and smoke and mirrors,” as framed up by Andy Pollack’s New York Times piece on Sunday (“Riding High, Biotech Firms Remain Way”). In the bull camp, there are certainly some fantastic new therapeutic advances coming from newly minted public biotechs, offering early but breakthrough clinical outcomes; many of these are sporting valuations commensurate with that promise. We’d all obviously like to believe this is a new era of sustainable capital markets support for high impact medical innovation – where the hype is supported by substance – but only time will tell if the high-flying companies of today and their product portfolios can mature favorably into their lofty valuations.

Adam Feuerstein also threw out some “controversies” to kick off the year – citing valuations, drug pricing, conflicts of interest, the “next Sam Waskal moment” and a few others (here). And David Grainger double-clicked on those themes, and adding his rather bearish bubble commentary, in Forbes earlier this week (here).

These three pieces clearly convey the tension between enthusiasm and anxiety in the public capital markets for biopharma today – as they are mostly focused on publicly-traded companies large and small.

But what about the private world of venture-backed biotechs?

The open IPO window has dramatically reduced the cost of capital for growing and scaling venture-backed biotechs, and has created lots of optionality for private companies thinking about their futures. Optionality is a good thing in any startup venture. Further, lots of recent news about the biggest quarter of “venture” funding ever recorded for biotech (here).

But underneath the headlines there’s a lot more nuance in the reality of private biotech ecosystem than meets the eye, so thought it useful to go through some instructive data around exits, funding, and startups, with some well known lyrical refrains from the Cars, Beatles, and Pink Floyd.

I. Exits: “Let the good times roll”

Life science venture capital firms have posted some great mark-to-market numbers over the past couple years, driven by the buoyant public markets and robust M&A.

As Mark Schoenebaum has highlighted, via Stelios Papadopoulous, last year witnessed the most IPOs ever in the history of biotech, outpacing even 2000 (here). Combined, the past two years have seen more IPOs than the cumulative total of the prior decade. Lots has been written here and by others on this IPO environment.

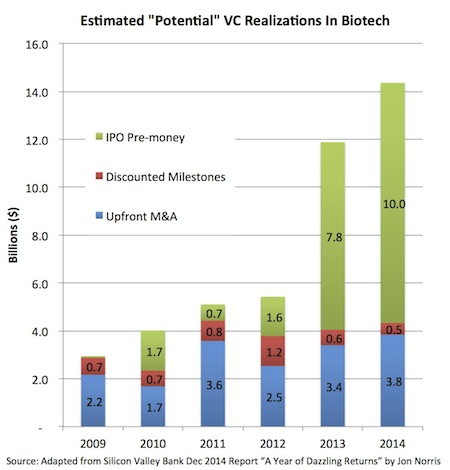

M&A has also been strong, as I’ve noted before (here), as the “silent partner” in driving liquidity. Silicon Valley Bank’s Jon Norris showed in a December report – titled “A Year of Dazzling Returns” – that biotech has seen 85 “big exits” over the past six years and their value has gone up steadily, reaching an average upfront and total deal value of $366M and $507M in 2014, respectively. These are 30-50% higher than just five years ago.

But exactly how much of this excitement has materialized as distributions back to firms and their Limited Partners (the investors in VC funds) is unclear.

SVB’s Norris and his colleagues also takes a shot at estimating this, and it’s as good of an analysis as anything I’ve seen. Below is the summary chart for biotech alone (not medtech/Dx). They make a few rather conservative assumptions (e.g., VCs own 75% of the companies at “exit”, only 25% of the aggregate milestones get paid, using pre-money of IPO as exit value, etc), and estimate that nearly $26B in real or potentially liquid distributions have been generated over the past two years alone. This is 3-4x more than has been invested over that period of time by VCs into biotech; distributions vastly outstripping investments is certainly positive biomarker for the venture sector.

A huge caveat to those numbers is required, however. Most VCs are still not liquid (i.e., have not sold or distributed shares) from their 2013 IPOs, much less the ones from 2014. Taking a look at the major holders of some of the early IPOs in 2012-2013 reveals that VCs still maintain very large positions (e.g., Epizyme, Agios, Tesaro, etc). As discussed in late 2013 (here), achieving liquidity from IPOs in thinly-traded stocks isn’t always easy but the run-up in 2014 certainly helped. Actual distributions are significantly different than the “potential” embedded in the chart above.

Cambridge Associates, a leading investment advisor, provides quarterly and annual benchmarks on venture capital as well as commentary. Their October 2014 letter highlighted that “VC Distributions Hit Highest Level in almost 14 Years” across all sectors in venture as of early 2014, and that “The Health Care Sector was the Top Performer in the VC Index”. My guess is that when the data is in on the second half of 2014, there will be further positive themes of strong distributions and solid performance from biotech and healthcare.

At the end of the day, sending cash home at good rates of return to LP’s is all that really counts in the venture business. Mark-to-market valuations are just paper until they are realized. Fortunately, this exit window has created a more liquid environment than at any point in the last decade, and it’s been a good time for realizations. Looking forward to seeing the data on the real returns from this bullrun for VCs in a few quarters.

II. Venture Funding: “With A Little Help From Our Friends”

Times certainly change. It was only three short years ago when most industry pundits (aka Chicken Littles) were yelling that the sky was falling on life science venture capital (here) when the quarterly funding numbers were down. The “death of life science venture” was widely heralded.

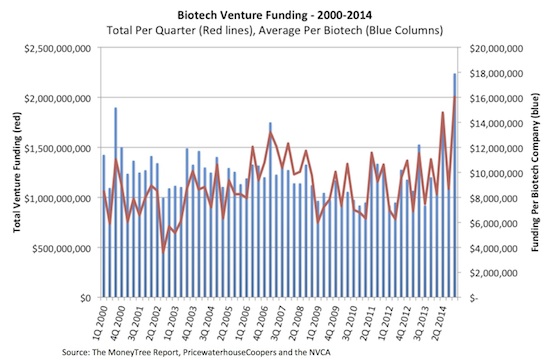

But in the last three months of 2014, “venture capital” funding into private biotechs posted the largest sum ever recorded in the history of the sector – just above $2 billion – according to the MoneyTree Report from PricewaterhouseCoopers and the NVCA.

These fund flows are obviously good for scaling companies and helping catapult them into the public markets or M&A with momentum. But its worth noting two very material nuances in the data around who is funding it, and who is getting it.

Who is driving this funding increase? Its not venture capitalists in the conventional sense.

The later stage financings that have been driving up the aggregate numbers are almost without exception driven by crossover investors (like hedge and mutual funds who typically invest in public companies) or non-traditional partners like big financial institutions. For example, the Alaska Permanent Fund put nearly $300M into Juno Therapeutics during their private rounds, and the eye-popping $450M raised by Moderna was filled out with a broad range of buyside, public-market investors.

On the early stage side, nearly one third of all Series A funding comes from corporate venture capital (CVC) – and this has been increasing over time, as discussed before (here).

My estimate, based on discussions with a few bankers who track crossover activity, and an appreciation of CVCs contributions, is that only around 50% of the $6B invested in private biotechs came from “conventional” venture investors (meaning independent venture firms backed by groups of LPs).

By comparison, in 2011-2012, privates biotechs raised ~$4.5B in each year, of which probably 75% was from these conventional VCs. So my conclusion is that its been roughly the same amount of capital from this group over time. This may change as new VC funds raised in 2014 and 2015 come online, but remember that only 15-20% of a new fund is deployed in Year 1 so even new fundraising by newly-flush conventional VCs is unlikely to move the funding needle quickly.

The second question is who is getting the funding?

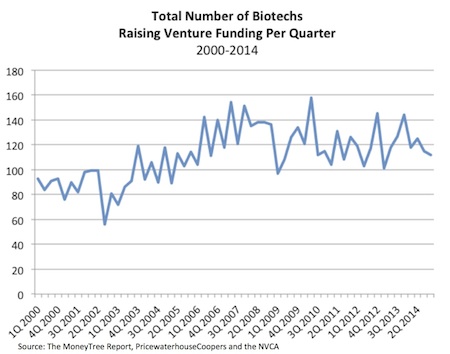

One would think with a big spike in aggregate funding that lots more biotechs would be getting financed. As the chart below reveals, the same number of private biotech companies got funded in venture rounds during the lean bunker-mode of 2009 as got funded in the bubblicious climate of 2014.

So with the increase in funding and steady number of funded biotechs, the same number of companies simply raised more money. Interestingly, this has almost always been the case in biotech. As simple math reveals (when you hold the denominator constant), there is a very clear correlation between the average raised and the aggregate funding over the past fourteen years. This is depicted visually below – the red line (quarterly funding) and the blue bars (funding per company) closely track each other. One could argue from this finding that there is nothing structurally new about the dynamic or volume of funding in the private biotech arena.

So in summary, venture funding levels have gotten higher in 2014 with a little help (a lot of help) from our friends outside of traditional “venture”– but there’s roughly the same number of “emerging” biotech companies getting the “venture love” out there.

III. New Startups: “Wish You Were Here”

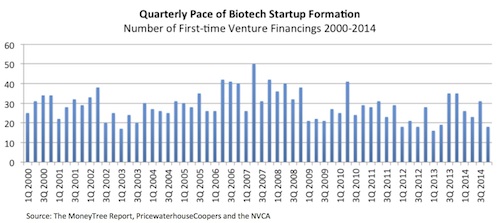

The reality is there still aren’t many of new biotechs being formed.

In fact, as a sector we started fewer biotechs in the booming 4Q of 2014 than in any quarter of the “bottom” in 2009 and 2010, according to The MoneyTree Report report’s “first financings” data. Only in two quarters of the last 14 years has the biotech sector started fewer companies than 4Q of 2014.

These data above highlight a staggering and glaring disconnect between the demand for innovation in biotech today and the formation of new startups to address that demand.

Unlike other sectors, where elasticity occurs between demand (where later stage/public investors are pouring capital or acquirers are buying companies) and supply (new startups to fill that demand), biotech reveals almost complete inelasticity – as I discussed in September’s posts on the “flux” of supply and demand in the biotech vs tech startup ecosystem (here), and the scarcity in early stage biotech (here).

The creation of new startups is vital to the long-term health of the biotech, and eighteen new startups doesn’t “replace” the private biotechs that exited from the venture ecosystem in the fourth quarter. With only a few venture firms, like Atlas, currently focused on the creation of new startups, the constrained supply of new companies is likely to remain in place for the near-term, at the very least. It also bodes very well for those of us starting the next crop of innovative young companies – producing limited supply to engage burgeoning demand.

But as Pink Floyd noted, it’s lonely in the fish bowl, year after year – we wish more folks were in the early stage ecosystem starting new biotechs and helping us build them.

Concluding Thoughts

It’s a great time for biotech – both in the public and private markets. The exit environment is the best its been in years, and created significantly more investor and Limited Parnter interest in the life sciences. This is a great thing after years in the doldrums.

But the nuances in the venture market reveal some of the structural aspects of the biotech sector. We don’t create very many new venture-backed companies, even in boom times, and the steady state number of maturing biotech companies getting funded each year hasn’t budged for much of the last decade. These feel like important structural constraints to recognize.

This reality helps restrain the exuberance of the current market, and despite the very positive exit tailwinds of 2013-2014, I don’t think we are anywhere near at risk of overfunding and over-competing in the startup venture-backed biotech arena.

Although certain areas, like CD19 CARTs and checkpoint inhibition, have instantly become crowded, there remain an enormous number of unmet medical needs, as well as innovative approaches to address them, that deserve and are receiving thoughtful and disciplined funding.