This blog was written by Jeb Keiper, CBO of Nimbus Therapeutics LLC, as part of the From The Trenches feature of LifeSciVC.

Unsurprisingly, I had not given that much thought to the parent entity of my new employer when I joined Nimbus in 2014 – what was the difference between an “Inc” and an “LLC” anyway, how much could it matter? The answer: plenty. In 2010 Nimbus Discovery LLC came out of stealth mode in a post called “Discovering Nimbus“, now Nimbus Therapeutics. The idea, born out of the capital crisis of ‘08-‘09, created structural flexibility for a platform company as it worked on therapeutic targets and has been well covered by prior blogs (here, here).

In April of this year, Nimbus announced an agreement where Gilead bought one of our program-focused subsidiaries, Nimbus Apollo, which comprised our entire ACC program, including the lead clinical molecule for NASH. This transformative deal, discussed here, gave an opportunity to, as one of our lawyers put it, “take the Ferrari out on the highway and really see how it runs”: a fitting test of this corporate structure. The track results are solid, but like any first run with the throttle wide open, some fine-tuning is necessary; so with that experience and working in this LLC model for 18 months, it is now time to blog about “life in the trenches” with this structure. I’ll focus on the operational aspects of starting, growing, financing, and recently, exiting and recycling capital within this structure, all while producing new medicines for patients. What comes next is a deep dive on the admittedly wonkish subject of corporate structure in the biotech space.

Program Subsidiaries – All About Flexibility

When Nimbus began in 2009, the initial architecture and framework involved two elements: (1) program-focused subsidiaries, and (2) the use of an LLC holding company for investments. The structure very much had “pharma BD partnering readiness” in mind to allow focus only on the assets of interest (program-focused subs) and allow a vehicle for tax efficient capital returns to investors (the LLC holding company), blogged about here.

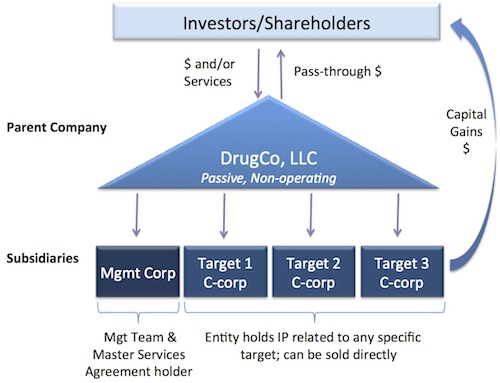

Let’s take a walk through the implications for both of those elements, starting with the subsidiary structure. As illustrated in the figure below, reference is made to a corporate entity with a holding company, a passive and non-operating LLC, as parent entity and multiple subsidiaries designed to solely hold groupings of assets, including the IP estate, of the enterprise (we’ll call these the “program subs”). The program subs usually exclude the employees, facilities, or a shared platform utilized by the entire entity since those elements are all held in a single sister subsidiary, the “operating company”. This operating company is designed to have multiple service agreements in place with each program sub to execute work on the program sub’s behalf and assign arising IP to that particular program sub.

Nimbus, Forma, RaNA, Spero, and others employ this structure and there are other “subsidiary structures” out there, such as F-Star Limited and PureTech PLC’s operating company architecture for academic spin-outs (an interesting aside regarding public market funding of the parent (here)). Since Nimbus’ formation, the use of these types of structures has grown in biotech, but as described in the previous blog posts (here), it is not the right structure for every biotech. Getting exact industry numbers on the corporate structure choices is complicated, but thanks to the Atlas team for their updated numbers here: 7 out of 29 Atlas-backed companies (Series A or beyond) used this LLC structure (~24%).

The flexibility this structure provides on the business development/ partnering front is a blessing. You can construct an equity-only transaction, an option to acquire or option to license, a traditional licensing deal, or intricate multi-asset development collaborations. That is not to say any of those deal types cannot be achieved with a traditional structure, but the subsidiary structure allows existing IP, arising IP, non-compete clauses, and the preservation of platform IP vs. asset IP to be easily identified and pre-packaged for a variety of transactions in a subsidiary structure. For example, in an M&A type transaction, everything relevant to the program can be lifted out, including CRO and CMO relationships, supply chain contracts, academic relationships, IP licenses, financial statements, governance and quality processes, etc., without disrupting staff, platform, or the underlying infrastructure.

Equity in Deal Making

The use of equity in deal making has been widely covered, along with it’s pros and cons. When the accountants are satisfied that you’ve balanced control and decision making between parties, using equity in place of cash can be very effective in aligning incentives. However, it can also create nightmares for deal doing with large organizations that are laden with additional bureaucratic oversight for equity transactions: I was once told by a pharma BD lead, “this deal won’t get done if we have to involve the CFO’s office”.

The accounting boffins have a point – using equity can create major accounting headaches, especially when keeping books under IFRS or an internal financial control system that favors expensing what could have been considered R&D balance sheet investments (in one crazy twist I’ve seen: charging equity investment as an expense on a shadow R&D Exec’s P&L, thus dis-incentivizing that person from equity deals to grow their pipeline). In these cases, using program sub equity in an upfront or collaboration may prove intractable.

At the end of the day, deals get done not because of a novel corporate structure, but because of the great science a biotech develops. Just because you have an LLC, each counterparty will have its own needs, preferences, and situations, and may well have very different requirements. Just take Nimbus’ partnering activities over the years: our recent ACC deal with Gilead is an acquisition (here), our IRAK4 Genentech deal is a traditional license agreement (here), our agriculture deal with Monsanto is an option-to-acquire (here), as was our research deal with Shire on novel rare disease biology (here), each executed with a different program sub.

Financing the Subsidiaries

The subsidiary structure gives flexibility in terms of financing as well and under this structure one could even contemplate having different investors investing into the program subs they want to support and avoid those they do not. In a model like the PureTech approach cited above, this can make sense; however, when there is an underlying platform or operating company, as there is with Nimbus, this approach could create problems. Fundraising for Nimbus is just that: fundraising for Nimbus. Our investors own a piece of the holding company, and since that parent entity is the only single shareholder of a program sub, the fractional ownership of any program sub is identical. This is a critical alignment mechanic, without which, if one investor had more $ in Sub A, and another had more $ in Sub B, how should the CSO spend her time? What if she spent more with Sub A than B? Could investors on the Board truly be unbiased in their counsel to management when they were differentially incentivized? Furthermore, the more advanced a single program is from the rest of the pipeline, the more this structure will beg for independent funding, split or other schism (as covered in this blog on the asymmetry of maturity challenge). (NB: the solution for some other structures is to have a different CSO for each sub, but then you’ve lost the talent efficiencies and platform leverage). That means fundraising for this particular structure that Nimbus and others have ends up being very similar to other biotech fundraising: we raise capital for our whole company, pipeline and platform, and spend it according to a budget process identical to what others with single entity structures practice.

Rise of the LLC

The LLC parent for a multi-sub structure is a natural fit: the intent of the LLC in this model is to invest capital into each program sub, which then spends that cash on services from the operating company and external CROs, etc. The LLC can give investors a tax efficient mechanism of returning capital once one of its subsidiary’s shares are sold, similar to what Private Equity firms or investment groups would do for their investments in public equities.

“This sounds great, sign me up!”

Whoa! Before rushing down that path, however, there are a couple of important points to keep in mind, which will impact your company differently by stage of growth:

- Start-up through Series A: the LLC structure is not simple to establish or operate – multiple entities need to be incorporated, intercompany operating agreements need to be put in place, control mechanisms and governance must be ensured, all with the risk that mistakes in the setup can be very difficult (and costly) to fix later. Have your best lawyer on hand (Mitch Bloom and his team at Goodwin Procter have been essential to Nimbus), and be ready to spend that seed cash and equity money on getting this right: it can pay off in the long term. A further wrinkle that argues for early LLC setup involves the creation of the subs themselves. Often times early IP is nucleated by the employees and platform in the operating company: it is essential to move that IP into its own stand alone sub early in its lifetime. That is going to require BoD authorizations, paperwork filings in Delaware, operating agreements, a new set of financial statements to track and audit, etc. Frankly, it is a daunting task for any early stage leadership team – and it is people who matter here. Holly Whittemore, Nimbus’ VP of Finance and Operations, has been at Nimbus from the beginning and has designed and orchestrated all of the legal and financial complexity for Nimbus; without her, none of this would fly.

- Growth into the Clinic: as your company builds out to grow and expand, the flux of capital into your organization structure increases: programs that originally had a burn rate of $3m per year progress to Phase 1 and $3m per quarter, and eventually Phase 2 and $3m per month. The LLC operating agreement (highly customizable documents, typically laden with investor protections), often make navigating future fundraising difficult, and in the extreme case of considering public equity markets, an IPO would require you to wind up this wonderful LLC structure you slaved over into a C-corp to list on the NASDAQ, as Intellia ($NTLA) did prior to their IPO. As an aside, with a bit of preparation the transition from LLC to C-corp is simple; the transition from operating C-corp to LLC is fraught with difficulty: if you are going to leverage an LLC, do it from inception if you can. Another snag in growth relates to employee incentives. Unlike typical C-corps, typical LLC’s do not have shares, they have members who hold “profits interest units”, and these “units” cannot be assumed to be like shares – often it is impossible to have an unused pool of units for new hires, so every single new hire requires Board or LLC member consent votes, and forget expansion of units or stock option analogs, both are nearly impossible. Furthermore, handling units for employees or others that have separated from the company are often treated differently than stock, and in many cases there are no simple remedies to issues of dilution and managing non-investor fractions of the cap table. Practically speaking, a good lawyer will tell you anything is fixable, you just might be spending your senior management bandwidth on resolving these issues so you can grow beyond 20 people or hire that key new executive, instead of on the science, platform, and talent themselves.

- Harvest: Let’s say you’ve managed the complexity, kept track of finances, advanced the science, and you finally get to a point where a transaction seems possible: make sure your suitor is aligned with your thinking. Those who ply the dark arts of business development know you may have multiple parties interested in your science, but one party sees an acquisition target, another sees a co-development relationship, and yet another sees an option arrangement. To the flexibility point raised above, you are set – your structure should enable any of those; however, the implications of each of them could be quite different: an acquisition recycles capital, but resets the company, a co-development deal could lay a path where you seek the public equity capital markets to bolster growth, whereas an option may fund one or two subsidiaries, but not others, with various ownership fractions and slightly skewed incentives. One of the more interesting, and difficult questions in a biotech LLC structure occurs when one of the program subs is acquired. Within an LLC, proceeds from a sale are distributed to members and charged appropriate capital gains rates – that part is straightforward. However, the tax burden for any LLC member is not based solely on the money distributed, but rather on the funds distributed plus funds reinvested in the rest of the company. This means if you sell one of your early-stage programs (using fictitious numbers here to make the point) for $50m, but the rest of your LLC investments on the balance sheet were $150m, some of your incentive unit members could owe more in taxes than they would have been distributed in actual cash (they would owe taxes on their portion of the LLC’s $200m). So that liquidity you thought you’d have with this structure vanishes, and starts creating incentives to sell off the most valuable part of the pipeline just when it is accelerating up the value curve. Watch-out as well for your company’s liquidation preference (especially participating preferences): an acquisition deal that falls below the preference stack is disadvantaged to be in an LLC from a tax perspective (both investors and employees would have fared better with a C-corp), whereas when the acquisition deal upfront is greater than the preference stack, an LLC is likely to be advantageous.

- Pharma’s Perspectives: The impacts of an LLC structure are not all about the smallco biotech – there are points for Pharma to consider as well. Acquiring a program sub is a much more straightforward endeavor than acquiring an operating company: acquire all the IP, datasets, regulatory interactions, and R&D service relationships with no leases to wind down, no employees to integrate or severance to pay out. Another plus for pharma with the program sub acquisition, beyond the balance sheet, is that after the deal is closed, the buyer does not have to deal with a sea of faceless investors, but instead can engage, and hold accountable for any issues, the parent LLC and management team since they are left intact (this last point isn’t always obvious until contract drafting, but ends up being critically important for pharma risk management calculations). The acquisition itself offers a bit more complexity for the legal and BD teams than a simple share sale, but it is eminently navigable for two willing parties.

- Planting new seeds: If you do get to that point of sale and have agreement on distribution, you will face the question of whether (and how) to reinvest any of the proceeds back into the rest of the company. You will effectively be thrust from deal celebrations into figuring out how to map future financing, complete with uncertainty around individual investor participation, conditions to meet, revisions to the operating agreement, governance concerns, talent flight risk, etc. Here you need to have steady investors and a phenomenal Board, which we at Nimbus are blessed to have, allowing us to avoid a dilutive equity raise in the near term. Commitment to the LLC structure, to the company and its mission, and to the team is critical to minimize disruption and keep management focused on the science and creating value.

Share the Experience

The use of program subs and LLCs as investment holding companies has been around for ages, but it is only in this last decade that creative investors, management teams, and lawyers have experimented with their advantages and disadvantages to solve some of the classic challenges in entrepreneurial drug discovery and development. Nimbus’ example is no longer unique, but the variety of situations and structures out there is multiplying. In the biotech ecosystem, we share our successes and failures to improve, and we hope in part this blog has been informative, so join us and share your experiences, good, bad, and ugly, with the LLC model so we can advance the field together.