In the excitement of today’s biotech IPO market, and the bullish period since 2013, it’s almost hard to remember how painful the equity capital markets were back in the day.

When I began my career in venture capital in 2004, the IPO markets were just opening up after the fallout from the bursting of the tech and genomics twin bubbles in 2001. Great companies like Atlas-backed Alnylam and Momenta were going public. Sixteen years later those two are a $15B commercial-stage biotech and a recent $6.5B acquisition by J&J, respectively – very successful biotechs by any measure. But most folks forget that their IPOs were really painful: both priced their offerings ~50% below the mid-point of the expected price range (here, here). This wasn’t an uncommon occurrence.

The IPO markets for most of the 2000s never warmed up much. Jazz Pharma, now a high flying $8B company, “took it on the chin” when it went public in 2007, nearly 30% below its target range. And in 2010, as things emerged from the Global Financial Crisis, the markets continued to be painful: for example, Anacor, acquired later for $5B by Pfizer, came in with an IPO that priced 70% below its target range; Pacira, now $2.5B, was 50% below its IPO mid-point; and Horizon, now $17B, priced its 2011 offering 20% below the range. And those are some of the winners.

Very much related to these challenging pricing discussions, valuations were also extremely constrained back then. Continuing a few of the examples above, Alnylam was preclinical and raised $35M at a $90M pre-money valuation, Momenta was in Phase 3 and raised $40M at $130M, Horizon was also in Phase 3 and raised $50M at $145M. Pre-money valuations during this period was often at or below the private investor cost basis in many IPOs.

In light of that rather bleak market context, in August 2009 I wrote a Nature Biotech article titled “Beyond the biotech IPO: a brave new world” which reflected on the “chronic deterioration in the viability of the public capital markets for the past decade.” It was indeed a challenging period.

During most of that decade, terms like over-subscribed, upsized and above-the-range were almost never used to describe biotech IPOs. Yet today, and to a large extent over the past 7 years, they are almost commonplace descriptors of new offerings. And valuations have also changed remarkably, particularly for early stage preclinical and Phase 1 stories.

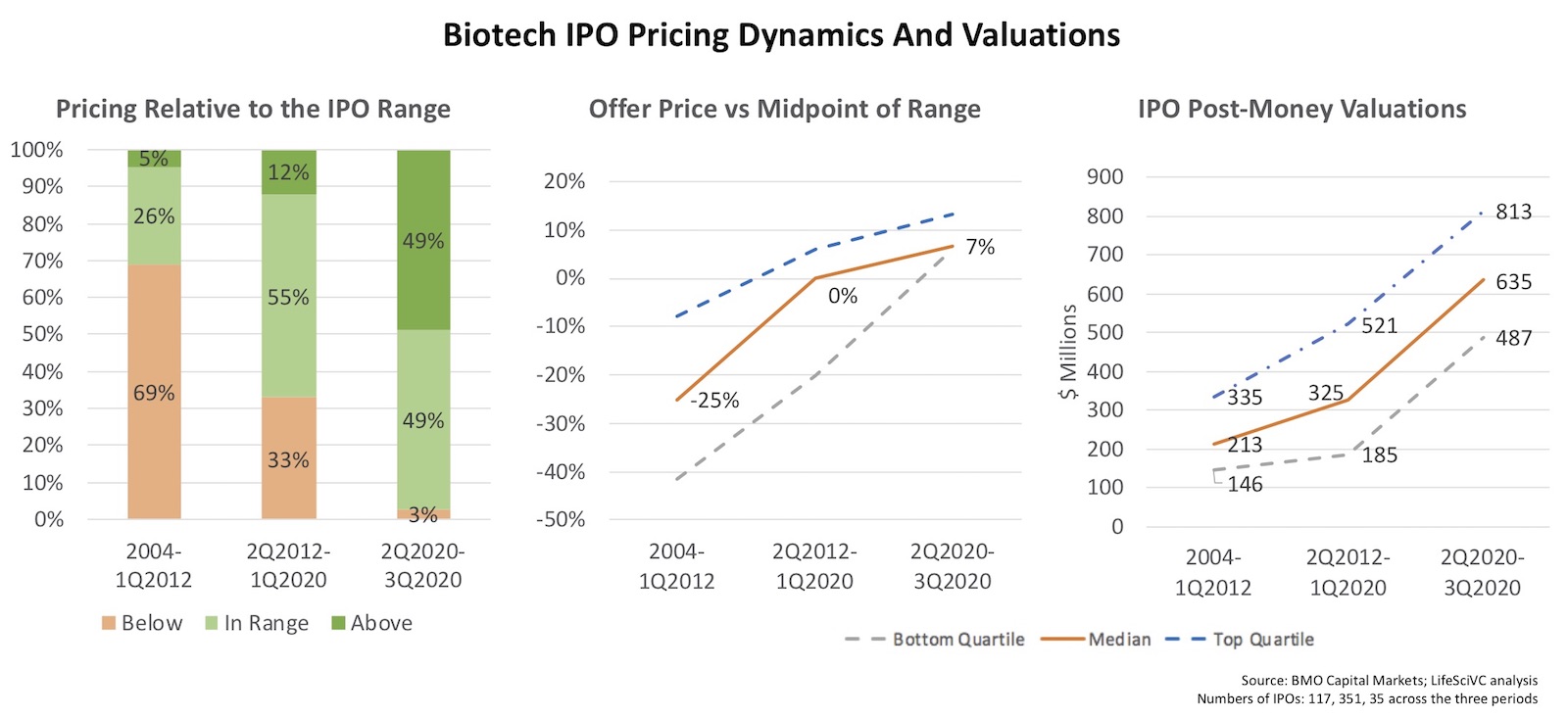

Before digging into the reasons why, here’s a snapshot of some aggregate longitudinal data, courtesy of BMO Capital Markets, relating to how IPOs priced back then versus more recently:

- Price discovery and IPO range setting has improved. From 2004 through spring 2012, more than two-thirds of IPOs priced below the range. In contrast, from mid-2012 through winter of 2020, two-thirds priced in the range or above. And since April 2020, 97% of the IPOs have priced in the range or above (all but one IPO). As the middle panel below shows, the median pricing relative to the mid-point of the expected IPO range was -25% in pre-2012 period versus 0% in the post-2012 period (meaning in the latter period pricing typically happened at the mid-point). And since April 2020, the median pricing has actually been 7% above the mid-point ($1 above the midpoint, so commonly referred to as the top of the range).

- Valuations have grown significantly. In the 2000s, the median post-money valuation was only $213M. That grew by 50% into the next decade to $323M, and more recently has exceeded $600M. A bottom quartile IPO today is valued above a top quartile IPO in the 2000s, and often has early stage lead programs.

The obvious observation from the two left hand panels is that there was pervasive and significant mispricing, or mis-setting, of the expected valuation range in the IPO process of the 2004-2012 period versus the more recent periods. The setting of a price range is often more art than science, and requires gauging likely but not certain IPO-buying behaviors before deciding on the optimal valuation guardrails. But it appears that eager bankers and aspiring biotechs got it wrong way more than they got it right in the 2000s.

And the clear takeaway from the right hand panel is that there’s significantly more demand for biotech IPOs today, and hence valuation appreciation.

So what changed in the IPO markets before/after 2012?

Two of the more well-appreciated responses involve (a) greater innovation and (b) the depth of the capital markets.

Biopharma has certainly been innovating and making new medicines that matter, and the markets have paid attention. As a sector we’ve taken the promises of the prior decades, like those around the Human Genome Project, and begun translating them into real medicines with impact. Think about the advances in precision genetic medicine, engineered cell therapies, gene therapies, oligos, and many others. Further, COVID and our response to it have highlighted the role of science and biopharma in leading us out of this crisis. These innovations are real and will continue to deliver, and the markets have taken notice.

Further, the equity capital markets for biotech are indeed much deeper: there is a lot more capital in the healthcare equity markets across biotech specialists at mutual funds, hedge funds, and even sovereign wealth funds. In particular, early in the period (2011-2015) several of the Big Biotechs drove significant outperformance of the NASDAQ Biotech Index, drawing more investors into the sector. Even though Big Biotech stock appreciation may have waned in the recent few years, many small and mid-cap biotech stocks have outperformed. All of this has deepened the pool of capital churning in the sector in search of the next big one. The feast or famine nature to risk-on/risk-off capital flows, characteristic of the biotech sector’s first 30 years, seems to have abated.

The greater capital market interest in biopharma has created a virtuous cycle for the sector’s IPOs. In the past, companies often raised less ($30-50M) at challenging valuations, could barely fund their R&D aspirations, and had to come back to the markets frequently. Given the small size of the raise, many large institutional investors couldn’t participate: their allocations would be far too small, and the illiquidity too constraining. Today, a much more positive cycle exists: companies are raising more capital, which gives larger funds opportunities to deploy meaningful amounts, which increases demand and raises valuations. These higher valuations enable raising more capital without taking on dilution beyond the typical 20-25% IPO range. More capital means more robust R&D programs and broader pipelines. A positive cycle, for sure, and one that has enabled larger generalist pools of capital to participate in the sector.

These two dynamics – innovation and the deeper capital markets – are certainly valid, and explain a lot of the increase in valuations and interest in the space.

But they don’t explain the more efficient IPO pricing process in the recent period relative to the 2000s with regard to the expected valuation range.

Two major structural changes to the way IPOs get launched explain that change: the JOBS Act and the rise of the crossover round have unleashed a much more efficient price discovery mechanism in the post-2012 era.

Jumpstarting IPO efficiency

The Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act is the unsung hero of the biotech IPO boom since its passage in 2Q 2012. While largely discounted by the tech sector, the impact of the JOBS Act on biotech IPOs can’t be over-estimated in my opinion.

Candidly, I don’t think any of the financial reporting or cost reduction elements of the law, widely touted as really important at the time for “Emerging Growth Companies,”have actually had any meaningful impact, as supported by other research (here).

However, the two primary “de-risking” elements of the JOBS Act were profoundly important in biotech:

- Confidential S1 filing. Before the JOBS Act, filing an S1 was instantly public and let the world know you were trying to IPO. For many aspiring biotechs without a good read from the public markets, this exposed them to huge “signaling” risk. S1s of less compelling stories could sit out there for months, sending the message to the public equity markets that the story was stale, mispriced, or uninteresting. Pulling an S1 was public too – revealing to the world that a company failed in their attempt to go public. These negatives carried large reputational risks. By allowing a confidential filing, biotechs could start the IPO process outside of the glaring eyes of the investment community. This also allowed them to be “ready” to flip their S1s public when the markets felt strong.

- Testing-The-Waters (TTW). In the past, when an S1 was publicly on file, biotechs couldn’t meet with public investors outside of the formal IPO roadshow. This meant a lot of biotechs were “going blind” on price discovery. They, and their bankers, had to make big guesses on price – and, as the data suggests, were often wrong. With the TTW process, while an S1 is confidentially on file, a biotech can meet with public investors to gauge interest. Feedback from TTWs, often with 40-60 investors, provides hugely valuable input into the likely demand for a biotech’s upcoming offering and setting the right price range for an IPO.

Several factors contributed to the uncertainty in pricing before the JOBS Act. Given the complexity of the science behind most biotechs, especially early stage stories, and the lack of insight financial “modeling” provides in many of these, jumping into a biotech IPO as a public investor is difficult to do after one short initial meeting during the traditional road show. This is in part why crossover investing has appeal: the ability to do deep due diligence in a private round to establish conviction about an upcoming IPO.

Furthermore, bankers competing for underwriting business are often picked for telling a management team and Board that their company is worth a lot. Perhaps a lot more than it really is worth. And without the TTW process of price discovery, the initial price ranges for many IPOs of the pre- JOBS Act era were inflated as a consequence.

The JOBS Act helped resolve those inefficiencies in price-setting.

Crossover rounds: the quest for alpha.

Crossover rounds are name given to venture financings that are meant as the last private round before a public offering and involve investors that are typically public market players. These have become commonplace today as biotechs chart their path to an IPO.

While nowhere near as frequent as in today’s market, crossover rounds did happen before. And they didn’t protect a company from mispricing their IPO ranges. Merrimack Pharma, priced just before the JOBS Act, had a marquee list of public investors in their last private rounds; unfortunately, MACK still priced below the range, 22% below the midpoint, in March 2012. Other 2010-2011 IPOs with public crossovers involved included Ironwood and Tengion, both of which came in below their targeted range. Much of the insider participation in many of these IPOs came from crossover investors, a characteristic that remains true today.

The “crossover phenom” in biotech really caught momentum in the 2012-2014 period immediately following the JOBS Act. This was in large part driven by the quest for alpha. Just playing the market indices wasn’t enough. To outperform, there was a belief you needed the alpha of picking the beset new IPOs and catching the pop. Generally speaking, biotech IPOs were performing well in that period (see here for 2011-2012, 2013, 2014), but in order to get a meaningful allocation and a good cost basis, many public investors would seek out these private rounds to secure positions. And, as noted in a blog here in 2014, the involvement of the best blue-chip crossover investors appeared to be a good biomarker for an IPO’s quality: better valuations, bigger raises, and stronger aftermarket performance in the 2012-2014 period.

The positive dynamic of meaningful crossover involvement has continued since that period. Crossover rounds have multiple benefits. As noted above, they allow public investors a chance to thoroughly evaluate a biotech before the TTW process. By doing so, they enable a biotech to build deeper relationships with important public buysiders. They also strengthen the balance sheet.

And they help guide the price of the IPO. Bankers love to use the “step-up” analysis to put guardrails on the IPO price: if the median step-up of the last 25 offerings is 1.4-1.5x, then that’s where they will typically start. Take a 40-50% premium to the price of the crossover round, and that’s often the mid-point of the valuation range. And with the crossovers providing significant insider participation in the IPO, they help to stabilize pricing around that expected range – or at least not below that range.

This crossover phenom has definitely contributed to the dramatic reduction in the frequency of “below the range” mispricings in the past few years.

New structural change: virtual IPO roadshow?

While crossover participation and the two major derisking elements of the JOBS Act are both continuing to support a vibrant IPO market, the reality is the traditional IPO process still creates a challenging tension on valuation for companies.

Crossover investors often just have a toehold position pre-IPO, and want to put a lot more capital to work in the IPO and beyond – so they aren’t necessarily incentivized for higher prices. The friendly cabal of thought-leader buyside accounts wield significant influence on how an IPO comes together.

Ultimately, it’s the sense of scarcity and demand that drives a truly successful IPO, and this sentiment is often borne out of how the early “book-building” process happens in an IPO. Do you have just 1x of the expected raise “covered” with demand by the end of the first day, or is it 4-5x? The faster that book builds, and with what quality, sends a very strong message to the market.

Traditionally, an IPO roadshow would take 7-9 days, interacting with 100+ investors and traveling all over the country. The IPO order book would build slowly at first, with many investors waiting to get a read of the sentiment from the underwriters. Further, the buyside would call each other and talk about the deal. There was always a weekend in between, when investors could further watch and wait to see how things were coming together. I won’t suggest there’s been collusion on constraining pricing, though there might be, but the orderly and rather prolonged process of the roadshow put most of the leverage on the side of the buyers, not the sellers (biotech).

This is where COVID comes in – and the launch of the virtual IPO roadshow. I think this is a structural change that flips that balance, helping biotechs regain some of the leverage and create a more efficient market for their offering.

The virtual IPO roadshow is typically only 4 days, and some stronger IPOs close their books on the night of the 3rd. Management teams “meet” the same number of investors, but they do it via videoconferencing without the travel friction and distractions. The book-building happens quickly, and exposes the company to less market volatility. If buysiders like the story, they can’t wait to see how the book builds over the first 5-6 days of a traditional roadshow. They need to put their orders in quickly or will miss out. The virtual roadshow helps inject some FOMO into the biotech IPO process, and that’s a good thing for companies.

The data appear to support this conclusion: since the first virtual roadshow in April 2020, nearly every IPO has priced at or above the range (as shown in the charts above). Demand has been strong, and upsizing above the range has been a common occurrence.

Of course, overall sentiment towards biotech has been strong since hitting the bottom in March and has obviously been a positive force for driving IPO demand. If (when) that sentiment cools, there will certainly be some less successful IPOs, especially if the quality of the stories declines in frothier moments. That said, we’ve had strong periods for the biotech equity markets since 2012, with robust numbers of IPOs, and yet never saw pricing at or above the range with this frequency. I think, at least in part, the strength of the recent IPO market is the result of a structural change associated with the virtual 3-4 day roadshow process.

Critics might also say if so many biotechs are pricing above the range it means the underwriters are underpricing them. If valuations were low, I might share this view. But with IPO valuations moving upwards, as shown in the prior chart, it’s hard to see merit in that critique in aggregate – though there is certainly mispricing (up and down) on specific stories.

Today’s IPOs are some of the most highly-valued offerings we’ve ever seen, and the price setting mechanisms in the S1/IPO process are much more efficient than before. There are still challenges with how the IPO process enables companies to access the capital markets, which in large part explains the rise of SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies) as an alternative path to “IPO” (and likely the subject of a future blog).

As we all know, a biotech IPO is really just a financing to help fuel an R&D pipeline – and today there’s much more capital being allocated to fund those pipelines. Of course, positive post-IPO performance is far more important than the IPO pricing event itself, and often reflects the generation of exciting data or deal-making that further advances the company’s prospects (or not).

But a healthy, efficient IPO process that unlocks strong demand in the equity markets is a critical step in the biotech lifecycle – and it’s evident there are many structural and market forces contributing to that positive dynamic today.

So what’s the next decade of IPO financings going to look like? Lots of reasons for optimism, but it’s anyone’s guess given how much has changed durably from a decade ago, and market cycles will always play a role.