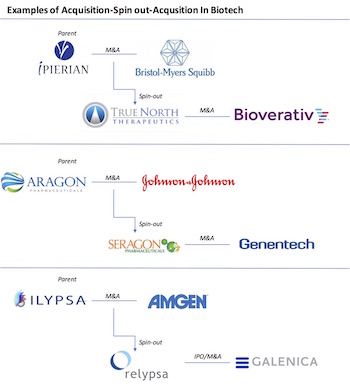

Lightning can definitely strike the same place twice, or so it seems in biotech. The latest example is True North Therapeutics’ recent acquisition by Bioverativ for its program addressing cold agglutinin disease, a type of rare autoimmune hemolytic anemia: it was a startup born out of a prior acquisition, where it was spun-out of iPerian following the latter’s purchase by BMS.

This acquisition-spinout-acquisition dance move solves for an important macro issue in biotech deal-making: in a multi-asset portfolio, one buyer may not want all the assets, or only assigns marginal value to them. This frequently leads to the suboptimal scenario of selling the entire company so that the buyer can get the lead asset, but not getting “full” value for the rest of the portfolio. These post-acquisition spinouts addresses the common “asymmetry of maturity” around R&D-stage portfolios in many biotech companies: the lead program is usually much further along in the R&D process, and thus drives the majority of the imputed value by the Pharma buyer while the other less mature programs go unappreciated. Negotiating to spinout the other assets at the time of the acquisition is one solution to this problem, but it’s not without its challenges.

Before sharing some thoughts on the overall approach, it’s worth sharing more color on the recent example of iPerian/True North for context. iPerian was started in 2009 as a merger of an East and West coast startups, Perian and iZumi Bio respectively, in order to develop drugs based on iPS cells. iPerian raised ~$80M over the next five years, in the latter part pivoting its business plan into antibody development. It’s lead program was an anti-tau antibody that BMS acquired in April 2014 for neurodegenerative conditions. As part of the asset acquisition, the team at iPerian spun-out their 2nd program, a C1 inhibitor called TNT009, into a new startup called True North. This new entity was launched with a Series A financing in June 2014 of $22M to fund development TNT009 in a set of rare diseases. According to Crunchbase, most, if not all, of the original iPerian investors participated: Kleiner Perkins, MPM, SR One, and several others. In 2015-2016, True North raised an additional $120M from blue-chip later stage and crossover investors, in three equity financings, to power up this asset-centric story, bringing TNT009 successfully into Phase 2 with an eye on taking it all the way. Bioverativ, in search of additional pipeline, acquired it earlier this week to “complement” its hemophilia business.

Getting two bites at the apple can help juice up the returns for all the shareholders. iPerian was acquired for $175M on a total equity raise of ~80M, a reasonable ~2x average multiple for a story that pivoted significantly from its founding thesis. Up to $550M in future milestones were promised, though BMS recently out-licensed the asset to Biogen (Bioverativ’s parent, funnily enough), so it is unclear how much of those economics were transferred to Biogen (versus being renegotiated as is often the case). For True North, it was acquired for $400M upfront, with up to $425M more in milestones, representing a good multiple on the invested capital over just a few years. Across both, an aggregate of $220M went into these assets for $575M in upfront value and up to $975M in milestones – roughly $1.5B in value. Some portion of this will go back to the original iPerian investors (through their initial ownership in the spinout and the equity they purchased along the way). Hard not to like those return numbers.

This isn’t a one-off example. This acquisition-and-spinout model has worked very successfully with other multi-asset stories as well.

Aragon/Seragon is a fantastic recent example. Rich Heyman definitely made lightning strike twice, as Xconomy noted (here). Aragon developed a new prostate drug against the androgen receptor, which J&J bought, and Seragon worked on breast cancer via the estrogen receptor, which Genentech/Roche bought. The combined pair of parent/spinout raised only ~$150M in equity capital and generated nearly $1.4B in upfront payments and up to another $1.4B in milestones.

A decade ago, when Amgen bought kidney disease Ilypsa in 2007 for $420M, a spinout called Relypsa emerged with earlier stage assets a few months later. Relypsa went on to go public and then get bought for $1.5B in 2016 by Galenica. Combined, Ilypsa/Relypsa raised $400M or so in private and public equity capital, and generated nearly $2B of value. Also over a decade ago, the Conforma/Cabrellis two-step was a great pair of returns when Biogen and Pharmion stepped up to acquire the parent and spinout within six months of eachother.

Other spinouts are “in the works” and hoping to get struck by lightning a second time: In 2015, after Naurex was acquired by Allergan, Aptinyx was spun out to focus on early stage NMDA modulation (here). Allergan also bought Taris Medical in 2015 for its lead bladder program, and Taris “2.0” was spun-out a few months later (here). And it doesn’t just happen with startups: J&J’s $30B acquisition of Acetlion will involve a large and well-capitalized spinout of an R&D NewCo with Actelion founder Jean-Paul Clozel as CEO.

Of course, the strategy doesn’t always work. Some of the progeny from prior spinouts have died or simply fallen off the radar: Novacardia/Sequel, Serenex/Coserics, Sirion/Revision, and many other parent/spinouts haven’t gotten hit with lightning twice. Such is the nature of drug R&D.

Stepping back to the big picture though, it’s clear this approach can create lots of additional value versus just leaving an under-appreciated asset in the buyer’s hands. Spinning out assets can bridge the gap on the upfront value between buyers and sellers, and harness the asymmetric information that a motivated management team may have about the unappreciated value of the other programs. Openness to a team’s desire to spin out the early stage assets can also be a differentiator amongst buyers in a competitive situation.

But the acquisition-spinout model isn’t always simple. Talking to Bill Collins, Kingsley Taft, and Mitch Bloom at Goodwin Procter, there are several things to think about regarding these models:

- Biotechs being bought need to fight hard for these early in a deal negotiation, before “anchoring” has set in on the part of buyers around the terms. Making this a core guidance principle of a deal in early discussions can be very enabling. Trying to throw this in at the end of the deal is typically not productive.

- Spinouts at the time of the sale work best when the assets are clearly distinguishable. Entanglements related to shared IP or platform insight can make these difficult to do. Discrete programs, with asymmetric maturity, make it “easiest” to do.

- Tax issues are hugely important as the spinout event creates a tax liability for the shareholders – it’s a taxable event to the extent that the spun out assets forming the NewCo have more than residual value. If the value is relatively high, the incurred tax will be high, and in many cases those spinouts just don’t happen. Understanding the tax nuances around value of the assets, and any potential NOLs to utilize, at the time of the spinout is important. Asset purchases (as different by equity purchases) can also factor into the structure.

- Spinouts need to re-form an investor syndicate and complete a financing transaction to capitalize the NewCo. As part of this, and related to the tax question, the “pre-money” value needs to be agreed on in a manner appropriate with fiduciary responsibilities to all shareholders. Given the sensitivity around this, especially with non-participating syndicate members and prior founders/team members, having an investor and executive group that likes working together and is on the same page is key.

- Management team expectations are real considerations. If the buyer wants key leadership team members to help drive the asset’s development forward post-closing, clear expectations (and agreements) around who is doing what in the spinoff versus remaining at the buyer need to be established, including “employee sharing” or transaction services arrangements.

It’s worth noting that another solution, perhaps more elegant, than the acquisition-spinout model is to plan for it in advance by utilizing the LLC-holding company structure where the individual assets are already in their own respective subsidiary C-corps. By converting to this model early in the life of a company, a biotech preserves all the traditional upside of a C-corp while retaining the benefits of selling individual assets. Nimbus Therapeutics sold its NASH program targeting acetyl Co-A carboxylase, housed in its Nimbus Apollo subsidiary, to Gilead in the spring of 2016 via this approach. All the other Nimbus programs continued to move forward without pause from the Gilead/ACC transaction.

It’s hard to argue that two (or more) bites at the apple aren’t better than one – so optimizing the opportunity to get that additional bite can be a big value creation lever for emerging biotechs.