Pharma R&D productivity continues to be a critical issue for the industry. Making smart investments in R&D requires an understanding of the risk and return drivers across the product development cycle, as well as some good fortune.

This week the topic of Phama productivity was once again in the spotlight with a Deloitte report out that highlighted a continued decline in the ROI of R&D – primarily focusing on impact of lower revenue forecasts on a “stabilized” R&D cost basis. It was widely covered across the trade media (here, here), so instead of focusing on its conclusions I thought it worth highlighting the risk part of the R&D equation – the success rate of programs in R&D.

Last summer’s BIO Industry report covered this topic in great depth across disease areas; in summary, the BIO data showed that the industry over the last decade had a 9.6% probability of success from IND to Approval. This is in line with similar analyses from McKinsey in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery from May 2016. The trend upwards (favorably) in the recent cohort (2012-2014) may just be an anomaly, but optimists like me think there could be real drivers behind the improvement (e.g., higher proportion of genetically-validated programs, more patient stratification biomarkers, etc).

External R&D models have also been proliferating across the industry, as companies adjust the proportion of investment directed to internal vs externally-sourced programs in their R&D budgets. The increased visibility of these “External R&D” models – like Celgene’s R&D partnership approach, Takeda’s Center for External Innovation, and Allergan’s Open Science model – shows how important they’ve become across the industry.

The goal of these efforts is to access the vast pools of innovation outside the walls of the in-house R&D organization and tap into the entrepreneurial risk-taking culture of biotech to secure a future pipeline, while avoiding the well-appreciated and suffocating burden of larger bureaucracies on creative research.

I’m convinced these efforts are likely to increase the overall R&D productivity of the industry. Precisely defined, R&D productivity involves both risk and spend. The risk part of the equation is particularly impactful – thousands of molecules are made to prepare a candidate for development, and only one-in-ten make it from IND to market. While there are clear cost benefits of working with leaner and more capital efficient partners (who lack the burden of large fixed legacy R&D infrastructure) especially as variable costs), I believe this risk component to the R&D productivity equation is where external R&D efforts are likely to have a big impact.

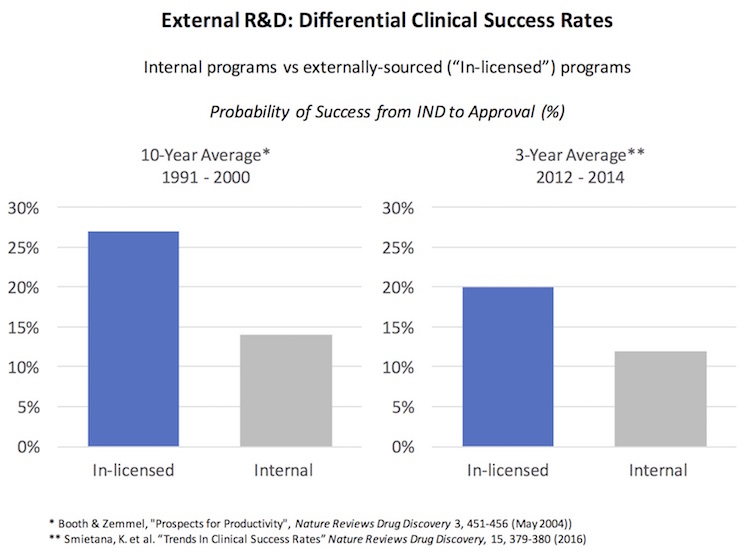

Here’s some historic and recent data to support that conclusion: over the past twenty years, externally-sourced programs (“in-licensed”) have delivered almost a 2-fold higher rate of success in development versus in-house programs. This was true in the 1990s (Figure 6b here), and its true more recently (here).

Why is this?

It’s certainly not the quality of the science itself. Lots of good science, worked on by good scientists, exists inside large Pharma organizations as “in-house” projects. We and others have successfully “externally-sourced” great programs from Pharma as the substrate for startups in biotech – and this is happening across many companies and disease areas today.

The differential success rate of externally-sourced programs is more likely a reflection of the sociology of organizations and the diligence process: the higher bar that an external asset must go through in order to find a place in a Pharma company’s R&D pipeline. An externally-sourced project has to displace other programs. It’s also competing with hundreds of other “external” projects for those limited licensing or partnership slots.

Beyond the operational and financial aspects driving this level of diligence, it’s also reinforced by conventional behaviors: the increased process rigor can be from paranoia (“these guys are hiding something, I should diligence harder”), internal career pressure (“I really don’t want to be the person that recommends buying a bad project”), or a host of other social factors (e.g., remnants of NIH syndrome – not invented here).

Overall, this competitive pressure around externally-sourcing creates a level of stringency and discipline in the diligence process that leads to, in general, the onboarding of higher quality assets. These data suggest the delta is considerable, and hasn’t greatly diminished in two decades.

These data are part of what underpins the differential in FDA approvals: two-thirds of the last five-years of new drugs originated from smaller companies, but two-thirds are launched by the larger companies. External sourcing has clearly been a big part of R&D success – and will likely be increasingly important going forward.

Lastly, are there things that can be done to improve internal R&D to shrink the gap in clinical success rates? BCG’s recent report on R&D performance highlighted operational effectiveness as a key distinguisher of the best organizations. I’d like to call attention to the last of the “imperatives” they highlight as part of truly effective R&D: “Promote truth-seeking behavior rather than progression-seeking behavior”. This is a critical point: it’s a culture change for many organizations, but super impactful. As they suggest, productivity might improve if a better advancement process was “implemented for evaluating internal assets, similar to the evaluation that is typically made on possible external assets”. There’s certainly a good deal of merit behind this recommendation.

These data, and the sociology they reflect, are further evidence for why the open source models of Pharma R&D are not only important today but likely to be even more important in the future.