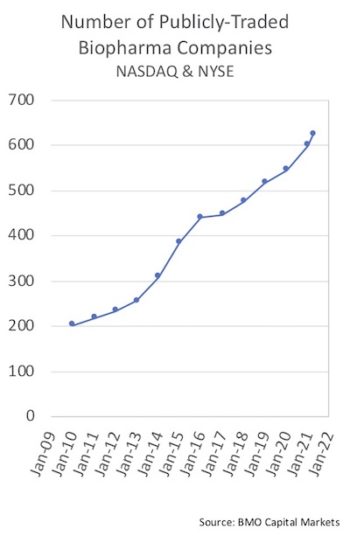

The universe of public biotech companies has been growing for a decade, and increasingly so in the past few years as the IPO market has flourished. Hundreds of young aspiring biotechs have tapped into the public equity markets, swelling the ranks of small- and mid-cap players.

While this expansion has been great for financing R&D pipelines, the rapid increase in the number of biotech companies hasn’t been matched with a similar increase in the number of “core” positions in most public investors’ portfolios – leading to a heightened battle for their mindshare and attention.

First, let’s review some data.

As anticipated with a robust IPO market, the public biotech ecosystem has been rapidly growing in the past decade, as reflected on previously here. After contracting in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the number of public biopharma companies has nearly tripled since 2012. As of March 2021, there were over 620 biopharma companies listed on the NASDAQ and NYSE, according to BMO Capital Markets.

However, the number of biotech-savvy buyside investors hasn’t kept pace with the number of newly public biotech stocks. While anecdotally there’ve been a reasonable number of new funds formed, these haven’t launched at the same pace as new IPOs or the growth of the biotech markets as a whole in recent years. In fact, as explained below, data suggest that many of the bigger and more established public biotech funds have actually grown faster than the overall market.

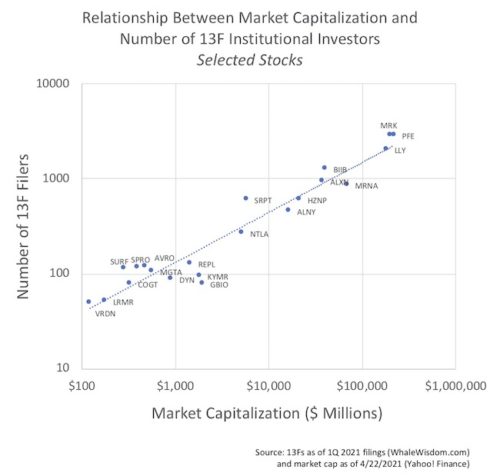

Though metrics of public equity fund formation and activity in biotech are hard to track, there are a few proxy data points that shed some light. Investor positions for any fund with at least $100M in AUM can be tracked by what the SEC calls 13F filings.

As background, the number of 13F filings scales with the valuation of companies in a linear way; a newly minted IPO may have 60-120 investors that are required to file 13Fs, which typically grows into 500-800 filers if the company is fortunate enough to get into the $10B market cap range, and Big Pharma’s often have more than 2000 filers.

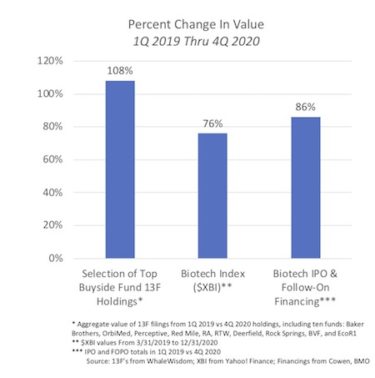

If the pace of fund formation for new investment managers was growing faster than the number of investment opportunities, you’d expect to see the growth rate of the AUM of a stable pool of existing blue chip biotech specialists to trail the growth of the overall biotech market (implying their “market share” was going down as new managers appeared). This hasn’t been the case.

Examining the 13F filings of a sample of ten of the most active crossover/biotech specialists (including Baker Brothers, OrbiMed, Perceptive, Red Mile, RA, RTW, Deerfield, Rock Springs, BVF, and EcoR1) across the 7 quarters, from 1Q 2019 and 4Q 2020, reveals an aggregate value increase from $40B to $83B, or a 108% increase. Some of this is by accretive performance of their portfolio positions, some by net inflows into their funds.

By comparison, total biotech financing activity (in dollar terms) for IPOs and public follow-on’s grew 86% over that period (1Q19 vs 4Q20), and the $XBI biotech stock market index increased 76% over that period (3/31/19 to 12/31/20).

By comparison, total biotech financing activity (in dollar terms) for IPOs and public follow-on’s grew 86% over that period (1Q19 vs 4Q20), and the $XBI biotech stock market index increased 76% over that period (3/31/19 to 12/31/20).

This delta (108% vs 70-86%) implies that despite the arrival of new managers, many of the bigger and more established managers are increasing, not decreasing, in their aggregate share of the biotech investing/funding market.

One of the many limitations of this analysis is it doesn’t capture differences in “where” investors play in the continuum of biotech companies, i.e., buying an IPO is different than buying Alnylam today, and some investors do more of the latter than the former. If anyone has better data on fund formation and activity, please share.

That said, I think the analysis is directionally correct around the principle takeaway: the pace of new names to invest in (supply of opportunities) has increased faster than the number of potential “big” holders of those names (demand for core positions).

Fund managers are frequently constrained by the number of true “core” positions they have, due to both mindshare of their team and the need for meaningfully-sized portfolio allocations.

Setting aside the huge long-only mutual funds (like Fidelity) that own large swaths of the biotech market, many of the best buyside investors in the biotech investing world only have 20-30 “core” positions, along with a tail of smaller “toe-hold” positions, irrespective of their fund’s assets under management (AUM).

Given the illiquidity of many biotech names, these big core positions only typically accrue by participating in marketed or structured biotech financings (e.g., crossover private rounds, IPOs, and Follow-On offerings). Buying these big “core” positions only in the open market would put significant upward pressure on the stock prices for most SMid-cap companies.

For an aspiring young biotech to build a successful and supportive investor base for the long-term almost requires becoming a core position with at least a few of the “blue chip” buyside investors. These funds often step-up in every financing with significant anchor orders, and they support the stock on the inevitable volatility dips. As an example, Baker Brothers did this with Synageva and Seagen over the past decade, buying into their equity financings as supportive insiders with strong conviction.

But the number of core positions “available” in the industry only scales with the number of skilled and size-able investors, since most funds generally don’t have big positions beyond their core 20-30 names. Despite increasing in size (as shown in the data above), most of the top funds haven’t scaled by adding a proportional number of new “core” names. In short, their core portfolios have increased in valuation, rather than in the number of underlying stocks.

This is part of what has driven the feed-forward flywheel of crossover and IPO sizes and valuations: larger raises mean larger allocations that are more meaningful for funds, driving up demand for participation in those raises, which increases the valuation and enables ever-larger raises – and so the positive cycle feeds itself.

There are two ways for a fund to make room for new “core” positions. They can sell out of a position, believing their capital is better deployed elsewhere (due to either valuation levels or a loss of conviction on the biotech’s prospects). This trading obviously happens, and many observers track the 13F filing changes of the top funds (like this one, tracking EcoR1).

Or, a fund’s core position could be cashed out because of M&A. An acquisition recycles cash back into the fund for redeployment into new names. Over the past year, though, M&A has been rather quiet relative to past bull periods in this 10+ year super-cycle, reducing the relative role of recycling in fund-level portfolio reallocations of late.

So all these trends highlight the “relevancy challenge” in the biotech equity capital markets today: in an ever-expanding world of names, where the “supply” of possible core positions is outstripping “demand” for additional core positions, how does a biotech become or maintain relevance to the best long-term investors?

The obvious answer is to have an unusually compelling story to tell with great data revealing huge potential for transformative impact on patients. Much easier to say then to truly demonstrate, and “compelling” for an early stage story is often in the eye of the beholder.

But beyond the obvious, there are a number of things that can be important.

For achieving relevance, one way is to become a core position for a set of public investors before an IPO. This is the crossover phenom we’ve talked about in the sector for years, and it’s only increased in its importance over time. By building a diverse and deep investor base as a private company via appropriately-syndicated crossover rounds, you establish yourself as a core holding for a half-a-dozen or more key funds. But it’s a tricky Goldilocks formula: too many participants and the position will be immaterial so you won’t become a core name; too few participants and you won’t have broad-based support in the IPO and after-market. The same Goldilocks situation exists in how an IPO book is allocated.

These crossover and IPO allocations should reinforce the “core” positions of the best, “thought-leader” accounts who will be there for the long-term, as those are the funds that other investors will follow (e.g., if Orbimed or Perceptive are big buyers in the deal, others will want to be in the deal). Scarcity creates demand, but only as long as you’ve already ensured your biotech is a core position for some of the key investors.

As a young public company trying to achieve relevancy in the SMid-cap markets, there’s a multi-faceted approach that requires Board-level strategic prioritization. This includes detailed investor outreach plans built around the company’s key milestone/data releases, as well as medical and scientific meetings, publication strategies, and investor conferences.

The old adage is true in this relevancy-challenged world: always be selling. Not in an over-promotional way (a common mistake in biotech IMO), but in a credible, data-driven, and sophisticated way. You build support for the next financing by earning the respect and support of investors over the long run. In addition to good IR skillsets inside of companies, it’s often very valuable to work closely with IR firms and banks to help drive investor connectivity. Cultivate good relationships with a broad range of sell-side analysts, who can often help communicate a story within the context of a new space (e.g., where Company X sits in the neuroscience landscape). A management team with deeply credible reputation is often sought-after for advice about other topics by investors, further strengthening the respect and connectivity they have from the investment community. To this end, building your personal brand as a “thought leader” beyond your specific corporate role can be helpful. Remember, people buy from people they trust and respect – and investors are no different.

The bottom line is that achieving and maintaining relevance with the top buyside funds in an ever-expanding universe of investable opportunities only comes through hard work and planning, plus a healthy dose of good fortune in R&D. This buyside relevancy is critical to getting the attention required to access funding at a reasonable cost of capital – which is an existential requirement for success in loss-making R&D-stage biotech over the long term.