There are lots of myths about venture capital and biotech in particular, as noted previously on this blog. Many of these myths are deeply held beliefs about returns, what works and what doesn’t, and the state of the industry. Told often enough, these beliefs are presumed to be true by many observers, including practitioners in the field, Limited Partners, and pundits.

Surprisingly, data exists to address lots of these points, and I’ve attempted here to summarize (and link to) a number of prior posts aimed at debunking these myths and sharing a few observations on them.

So here are the top six myths or misperceptions about the biotech venture industry:

1. Returns in Life Science venture investing lag other venture capital sectors. The data do not support this premise. Both in an analysis by Bijan Salehizadeh and myself in Nature Biotech (here), as well as in an unpublished analysis from Correlation Ventures, healthcare venture capital actually outperformed all other venture sectors in the past decade, in particular with realized returns. In the latter study, healthcare services, followed by biopharma, were the two best sub-sectors in venture. This outperformance exists at the median, top quartile, and even top decile return thresholds for the last decade. As this chart shows (republished from here), of all the deals with an initial financing between 2000-2010 that have exited, roughly 8% of life science deals vs 4% of tech deals delivered above 5x realized returns.

One part of the disconnect in perception is the impact of unrealized returns on holding values of funds, especially during fundraising cycles. The “paper” value of write-ups looks good and validate the “market value” of a deal, but these are notoriously poor predictors of realized returns for a fund: as cited in a Kauffman report last spring, “write-ups in value prove seductive to [LP] investors even though they are not consistent predictors of a fund’s ultimate performance” (here). Further, they significantly bias against Life Sciences due to the “unrealized return problem” (discussed here by Bijan); “Tech unrealized IRR overstates actual tech venture realized returns and Healthcare unrealized IRR understates it.” One example is Avila Therapeutics: it was held at roughly the same share price for 18 quarters (~cost) and then in six months was written up to its ~6x exit value. Its hard to argue value wasn’t being created during the preceding 4.5 years.

But a bigger issue underlying this perception is the reality of the “long tail” of the return distribution. This is best summed up by the question of why aren’t there life science VC funds with >5x-fund level realized returns, like Accel’s Fund IX? It is most certainly true that the top-performing dozen or so IT-biased venture funds do massively outperform other sectors and have powerful brands as a result. This is because of an important caveat about the distribution of outcomes: healthcare outperformance described above doesn’t hold at the top <1% part of the return distribution. Biotech lacks real exposure to those high profile “halo” IT deals that deliver 100x+ returns. But those deals are 1 out of 700 (here): of 25,000 startups formed in the last decade, 35 exited above $1B in value. Since there are 400+ active VC funds today, statistics would suggest that the 95%+ of venture funds will never score a halo deal. With statistics like this, its also hard to maintain persistence of performance: Kleiner Perkin’s recent acknowledgement of weak results was tied to a “lack of home-run internet investments” since its 1999 Google-dominated vintage (here). This is a big driver of the state of “haves” and “have nots” in the venture world; its very hard to raise a IT-focused fund without at least one halo deal under your belt in your past few fund vintages, or at least the perception of buzz that a halo deal is likely to be forthcoming in the next one. To be a top 5% venture fund today almost by definition requires some exposure to a halo deal outcome. This is where hybrid fund models (here) are particularly interesting: in diversified strategies, a good healthcare team offers the potential of stable top quartile-plus returns with the possible outlier of a halo IT-led outcome. Avalon is a good example of this with Zynga. These are the nuances of return distributions. As an asset class, it’s hard to claim that only the top 5% of funds matter since much of the capital is allocated elsewhere. As an industry, we need to be able to deliver attractive returns at the top quartile at the very least, and this is where healthcare can do and does very well.

2. When biotech deals blow-up, they blow-up big. Said another way, this myth goes “when you lose money in biotech, you lose lots of it”. The data also do not support this perception. I discussed this point in a blog post last fall (here). In an analysis from Adams Street Partners, different venture capital sectors were compared by their capital-weighted loss ratio (i.e., what percentage of dollars flow into money-losing deals by sector, not just what percentage of deals are loss-making). They found that biotech had a 36% ratio, vs Internet at 59%. This analysis was further validated by a large LP’s proprietary database: healthcare had a ~40% capital-adjusted loss ratio vs >60% in technology/media/telecom. This higher loss ratio in tech is presumably driven in part by deals that raise money at high valuations and then come back to reality in subsequent rounds. These data do suggest, however, that the belief that firms have historically been able to kill their tech losers early on small amounts of capital isn’t well supported: if it were, you’d see lower capital-weighted loss ratios in tech (more deals dying but less dollars invested in them). More recently, some firms (like Atlas) are exploring seed-led strategies aimed at reducing the post-Series A loss ratios that may change these data in the future.

3. Biotech takes far longer from inception to “exit” than other sectors. A post earlier this month (here) dealt with the data behind this point. Biotechs seem to go public “younger” than their tech counterparts, and M&A happens at roughly the same time. For “interesting” >$100M exits, they appear to occur faster in biopharma than in tech sectors. I won’t repost the charts, or the lengthy dialogue, but you can read it here. Lots of caveats to this analysis are included as well. An important one being that holding period isn’t the same thing as time from founding to exit. But its fair to say the data do not support the perception that biotech takes longer.

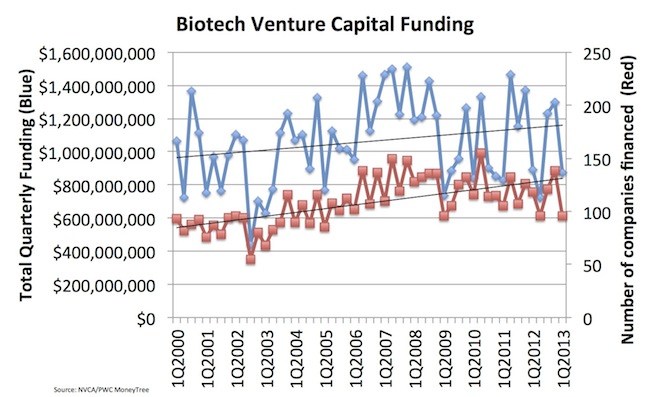

4. The overall biotech venture capital funding environment is drying up. I heard last week a discussion about “have we hit the bottom yet” – implying that we’ve seen a collapse in funding. This one makes me scratch my head as the data is easy to assess with NVCA/PwC Moneytree based on data from Thomson Reuters. Check out the chart below. This is overall biotech venture capital funding by quarter for the past 13 years (blue lines) as well as total number of biotech companies getting financing (red lines). Although we have considerable quarterly variation, the trend line is slightly up, not down, over time. When comparing the last two years to the distribution of fundings in the past 53 quarters (since 1Q 2000), we’ve had three “top-quartile” funding quarters, and three “bottom-quartile” funding quarters. Those latter “soft” quarters seem to bring out the Chicken Little commentators in droves. Yes, there’s lots of variability for sure, but this isn’t the sign of a venture capital funding environment that has “collapsed” or “hit bottom”. With an average of ~100 financings per quarter, these data are inherently very lumpy; however, on a 12-month rolling basis it reflects an active flow of financing.

5. Early stage venture capital is even worse – it’s a “barren wasteland”. This is typically said as a corollary to #4 above. And its true that “first-time financings” are indeed down in the NVCA/PwC Moneytree data– compared to the past 53 quarters as before, five of the last eight quarters have been “bottom quartile” in the number of new startups. The number last quarter hit the 1995 quarterly number, which is indeed disturbing. But first time financings aren’t the only definition of “early stage”. A $1-2M seed financing can be a first time financing event, or a $40M Series A. Those are obviously different. Same with a “Series B” into a drug discovery platform company whose lead asset is in preclinical – most observers would call that an early stage company. So I’d caution against high-level conclusions without digging into the underlying mix of data. In the past I’ve examined different definitions about “What is Early Stage” and how the data around financings stack up to them: check out the post here. I found that 60% of the biotech deals done in 2011 were into “early stage” deals. Although I haven’t updated it for 2012 or 1Q 2013, I have no reason to believe that this has changed since 2011 in a material way. By my guesstimate, in the Boston ecosystem alone, Third Rock, Flagship, Polaris, and Atlas have probably started/seeded ~25 companies in the past 1.5 years. There are still lots of interesting new and emerging early stage startups being funded.

6. Life Science VCs can’t raise new funds. Venture capital fundraising is tough regardless of your sector, and lots of “zombie” venture funds across all industries are out there that aren’t likely to raise new funds. And it’s particularly tough in LS today to raise funds, especially in a world driven by big venture brands, anecdotal stories, and a limited number of halo deals. But funds are being raised. While the media covers Scale Ventures’ move to shutter its healthcare practice, Sofinnova Ventures quietly shuttered its technology investing in its 2011 fund (here). New healthcare-only funds like Third Rock Ventures’ Fund III, Longitude Fund II, and more recently Lightstone Ventures’ Fund I have been raised. Index Ventures raised a healthcare only fund to complement its core tech fund. Hybrid funds like NEA, Polaris, Canaan, Avalon, etc have all raised funds recently. It’s not easy, but funds are getting raised. To get a sense of the available capital for startups, those fundraising efforts need to be combined with the huge influx of corporate venture capital that our sector has witnessed. GSK’s SR One and Novartis Venture Fund are two of the largest healthcare-only funds active in all of venture capital, as I’ve noted before (here). When commentators claim less is being raised in Life Science VC than being invested, most fail to account for $500M-$1B in Pharma corporate venture capital that gets allocated annually.

I’d love to hear from readers if the data-driven debunking above doesn’t align well with analyses from others, or if there are other myths worth tackling with further analyses.

For those of us in the trenches of venture capital every day, we constantly here the myths above: at meetings with fellow investors or entrepreneurs, at conference panels and discussions, and often at meetings with limited partners. The latter group is obviously important for the venture world, and one where brands and momentum often matter more than data, especially as the partners in firms evolve.

One of our LPs raised a provocative point in a recent email that part of the issue regarding Life Science’s “ugly step child” status in venture is the perception that there are no great healthcare venture “brands” today – many of the early ones with solid track records in the 90s (Oxford, Healthcare, Prospect, etc…) have been unsuccessful in either raising new funds or generating top quartile returns recently. Some of those and others have struggled to evolve their firms. No doubt there are still a number of very good 20+ year old healthcare-focused firms (e.g., OrbiMed, Sofinnova, etc…), but creative marketing and branding isn’t in the DNA of most healthcare firms. Healthcare teams within diversified firms may be an important part of maintaining their firms’ brands, but its still hard to hold mindshare of LP’s with drug discovery startups when a micro-blogging site they can touch and feel is up for discussion. Dan Primack’s point earlier this week sums it up: “why are us media folks so obsessed with the acquisition of a low-revenue blogging platform and so dismissive of an $11 billion combined revenue company that tries to cure disease and improve health? For one, it’s easier for most of us to understand what Tumblr makes than what Actavis or Chilcott make. Second, it’s a tech story and there are far more tech-focused media sites than healthcare-focused media sites”. As a related point, there aren’t a lot of active biotech VCs in social or digital media; of course LP’s want returns first and foremost, but they also want to see thought leadership and market-level brand awareness. Newer healthcare-only firms, like Third Rock Ventures and Longitude, certainly have real brand momentum with the market and LP’s, but only time will tell if top-tier returns can be consistently delivered. Interestingly, this LP also stated that in healthcare lots of LP’s today want to find managers with “novel strategies” and outside-the-box models of life science investing, whereas in IT-investing most LP’s believe many of the top tier venture brands will continue to deliver on their tried-and-true model of tech venture capital. An interesting dichotomy.

Hopefully in the next decade Life Science venture can break free of these myths and can get its mojo back – we can’t let misperceptions become reality, our collective brands do matter, and so do data around realized returns. Lets strengthen all of these going forward.